Writing / Reviews

Nour Mobarak, dafne Phono

Review for Visual Arts Ireland, Nov 2023. Guest edited by Orit Gat.

The morning after I saw Nour Mobarak’s interspecies performance installation Dafne Phono, I woke to a ghostly choir of dissonant angels. In that hazy space between sleep and wakefulness, I listened, head frozen on my pillow, beguiled, bemused, slightly concerned (is this real??) as a swell of voices glanced around my body.

The experience of listening, seeing, moving through the sculptures, soundscapes and provocations of Dafne Phono is an all-encompassing, dreamy, unhinged experience with long-lingering after-effects. It is hugely complex, madly ambitious and impossible to detail in a short bit of text, but here are some bones to frame the conversation. We are in a municipal theatre in the Greek port of Piraeus, a neo-classical interior with plush red velvet seats and tiers of gold-crested balconies. The stage is set with a tableau of sculptures that take the form of truncated columns, an enormous prism and clam shell, a skeletal spine, and a snaky, luminous green, amoeba-like form. Human voices, bird song, music and other sounds emanate from the sculptures, linked - we presume - to a screen that provides a scripted translation of the narrative. These bodies speak, sing, chime over each other, creating a lilting cacophony of polyphonic sound.

Mobarak has taken the world’s first opera La Dafne, composed and written in 1598 by Ottavio Rinuccini and Jacopo Peri, and translated each of the four main characters’ lines into fantastically distinct and distinctive languages. In search of the widest possible palette of human vocal sounds, her forensic research led her to some of the most phonetically complex languages still in existence. Each voice speaks or sings the myth of Daphne and Apollo, as told by Ovid in his Metamorphosis, in which Daphne’s polite but firm rebuke to Apollo’s advances (‘Other than my arrow, I do not want any companion; farewell.’) are met with the threat of rape. She morphs herself into a laurel tree to escape his will and remains forever trapped in this new form, while Apollo sits in her shade playing love songs on a lyre, with all the tone-deaf commitment of a romantic aggressor.

Mobarak extends this metaphor of the silencing of Daphne to the eradication of thousands of languages, animals, insects and plant species that has taken place over the last century under the sway of global capitalism and the machinery of extraction. The sculptures assume the language of nature in their live, rhizomatic form: in an act befitting the most committed of artists, Mobarak spent two years growing the mycelium (a network of fungal threads) from which they are made. Collaborating with a mushroom farm on Evia, an island near the Greek mainland, she spawned, dried, petrified and sculpted these strange hybrid shapes, making things that defy our entrenched view that animate things must at some point become inanimate.

It is a rhizomatic story in which artforms (music, art, poetry, literature), timeframes, and entirely divergent approaches to life, culture, modes of communication and thought are mobilised to investigate a rich spectrum of subjects including violence, translation, destruction, power dynamics, re-growth and repetition. Things are broken down into their constituent parts (language into morphemes and phonemes, music into sound and noise, biological life into cellular matter, sculpture into its raw elements), and refashioned, ready to be made afresh.

All this promiscuous intertwining of elements and disciplines is steeped in Mobarak’s life trajectory. She did seven years of classical voice training as a teenager; her great, great grandmother was an Ottoman court pianist; her mother was a Lebanese radio DJ and TV personality; and her father speaks four languages (her sound work Father Fugue, 2019, is an achingly tender exploration of his long-term neurological condition which dictates that he can only sustain a line of thought for thirty seconds). She studied literature and media, is a costume designer, performance and voice artist, actor, poet and musician. Through these multi-channelled forms of communication and modes of play, Mobarak examines embodied and spontaneous approaches to art-making that is driven by the understanding that metamorphosis is the underlying principle that propels the universe.

While I sit in this plush seat (the ghost of Susan Hiller hovering above me, her love letters to dying languages scattered at my feet), I understand that what I am looking at and listening to could never live up to its author’s ambitions. They are too strange, unwieldy, and wild for our familiar three-dimensional world. The work requires a fourth dimension, another portal, of language, space-time and ‘objectness’ to do what it is striving to do, but it is this mode of experimentation, this generative and generous offering of and to multiple artforms, that is the thing that makes Mobarak’s endeavour so rich and worthwhile.

The experience of listening, seeing, moving through the sculptures, soundscapes and provocations of Dafne Phono is an all-encompassing, dreamy, unhinged experience with long-lingering after-effects. It is hugely complex, madly ambitious and impossible to detail in a short bit of text, but here are some bones to frame the conversation. We are in a municipal theatre in the Greek port of Piraeus, a neo-classical interior with plush red velvet seats and tiers of gold-crested balconies. The stage is set with a tableau of sculptures that take the form of truncated columns, an enormous prism and clam shell, a skeletal spine, and a snaky, luminous green, amoeba-like form. Human voices, bird song, music and other sounds emanate from the sculptures, linked - we presume - to a screen that provides a scripted translation of the narrative. These bodies speak, sing, chime over each other, creating a lilting cacophony of polyphonic sound.

Mobarak has taken the world’s first opera La Dafne, composed and written in 1598 by Ottavio Rinuccini and Jacopo Peri, and translated each of the four main characters’ lines into fantastically distinct and distinctive languages. In search of the widest possible palette of human vocal sounds, her forensic research led her to some of the most phonetically complex languages still in existence. Each voice speaks or sings the myth of Daphne and Apollo, as told by Ovid in his Metamorphosis, in which Daphne’s polite but firm rebuke to Apollo’s advances (‘Other than my arrow, I do not want any companion; farewell.’) are met with the threat of rape. She morphs herself into a laurel tree to escape his will and remains forever trapped in this new form, while Apollo sits in her shade playing love songs on a lyre, with all the tone-deaf commitment of a romantic aggressor.

Mobarak extends this metaphor of the silencing of Daphne to the eradication of thousands of languages, animals, insects and plant species that has taken place over the last century under the sway of global capitalism and the machinery of extraction. The sculptures assume the language of nature in their live, rhizomatic form: in an act befitting the most committed of artists, Mobarak spent two years growing the mycelium (a network of fungal threads) from which they are made. Collaborating with a mushroom farm on Evia, an island near the Greek mainland, she spawned, dried, petrified and sculpted these strange hybrid shapes, making things that defy our entrenched view that animate things must at some point become inanimate.

It is a rhizomatic story in which artforms (music, art, poetry, literature), timeframes, and entirely divergent approaches to life, culture, modes of communication and thought are mobilised to investigate a rich spectrum of subjects including violence, translation, destruction, power dynamics, re-growth and repetition. Things are broken down into their constituent parts (language into morphemes and phonemes, music into sound and noise, biological life into cellular matter, sculpture into its raw elements), and refashioned, ready to be made afresh.

All this promiscuous intertwining of elements and disciplines is steeped in Mobarak’s life trajectory. She did seven years of classical voice training as a teenager; her great, great grandmother was an Ottoman court pianist; her mother was a Lebanese radio DJ and TV personality; and her father speaks four languages (her sound work Father Fugue, 2019, is an achingly tender exploration of his long-term neurological condition which dictates that he can only sustain a line of thought for thirty seconds). She studied literature and media, is a costume designer, performance and voice artist, actor, poet and musician. Through these multi-channelled forms of communication and modes of play, Mobarak examines embodied and spontaneous approaches to art-making that is driven by the understanding that metamorphosis is the underlying principle that propels the universe.

While I sit in this plush seat (the ghost of Susan Hiller hovering above me, her love letters to dying languages scattered at my feet), I understand that what I am looking at and listening to could never live up to its author’s ambitions. They are too strange, unwieldy, and wild for our familiar three-dimensional world. The work requires a fourth dimension, another portal, of language, space-time and ‘objectness’ to do what it is striving to do, but it is this mode of experimentation, this generative and generous offering of and to multiple artforms, that is the thing that makes Mobarak’s endeavour so rich and worthwhile.

Hopeful Futures

Response to Steve McQueen's Year 3 project, Art Monthly Jan 2020

Hopeful Futures

The unanimous praise for Steve McQueen’s Year 3 photographs at Tate Britain, a collective portrait of a generation, has been overwhelming – garnering plundits such as ‘profound’, ‘celebratory’, ‘deeply moving’ – but, if this is the sum total of our response, are we not denying the power of art? Yes, there is much to celebrate here. Year 3 is an inherently hopeful statement: pick any school photo of seven-year-old children from across the world and you will experience the powerful looping effect of projection and reflection. Hairstyles and uniform policies may change, but those desperate grimaces and carefully choreographed seating arrangements remain the same. And, as McQueen has said, the photographs provide those kids with a rare and precious opportunity to step outside themselves, to see themselves through the eyes of others. On my various visits to Tate Britain the atmosphere was electrifying, with huge groups of children rushing around trying to find themselves.

One of the most exciting things about art – particularly art in the public realm – is that it exists within a precise political, social and environmental context. Year 3 was initially planned for 2012 to coincide with the Olympics at a time when the catastrophic results of the Conservative government’s austerity programme, established in 2010, had yet to kick-in. Yet 2019 presents an entirely different landscape, in which the fifth wealthiest country in the world has one of the highest rates of inequality, teachers are crowd-funding to buy toilet rolls and food for their pupils, schools are shutting early on Fridays because of a to lack of funds and support for children with special needs has been decimated. In today’s Britain, a child loses their home every eight minutes – that’s 183 children every day. The number of homeless children in London has risen by a third since 2014 and is now equivalent to one in every 24 children. This means that many of the photos in Year 3 include a child who is homeless. Add to all of this the impending climate catastrophe and the toxicity of Brexit, and we have a very different set of ‘hopeful futures’ for the majority of kids depicted here (Greta Thurnberg’s cutting words to the UN come to mind: ‘You all come to us young people for hope. How dare you’). What seems to be missing is the critical dimension that pervades the work and yet remains unspoken.

It should be acknowledged that Year 3 is an extremely valuable piece of social documentation and a call to arms. Here, on public display, we are witness to the extreme inequality present in the British education system which involves access to privilege for a select demographic attending private schools. We see differentiation according to race, religion and, most alarmingly, class sizes (imagine teaching 14 children rather than 30); our peculiar insistence that small children wear uniforms; and, finally, the telling gender imbalance of teachers – poorly paid, under-valued, overly reliant on unremunerated care: that’s women’s work.

Alongside the exhibition at Tate Britain, Artangel has mounted a selection of these class photos on billboards in the streets of London. This is where the rich, complex, knotty context of the public realm comes into play. What happens when you put a photo of one of those single-sex, blazered, 14-to-a-class cohorts (I would hazard a guess they are from a West London private school), on Barking High Street, in London’s most deprived borough? Can this still be touted as a glorious celebration of multicultural London?

It is salutary to acknowledge that if Year 3 was pitched as anything but a celebration, it is unlikely it would have received the considerable amount of funding required to bring it to fruition. In the run-up to the election, this project could plausibly be marketed as a Conservative Party stunt: ‘Everything’s fine – look, they’re smiling.’

Tate says the work is a hopeful portrait of children who will shape the future, but you could draw a circle around the small number of kids who will get a chance to shape that future. The artist says there is ‘an urgency to reflect on who we are’ – so let’s do just that. Let’s honour the work, and the next generation, with a meaningful discussion about those hopeful futures.

The unanimous praise for Steve McQueen’s Year 3 photographs at Tate Britain, a collective portrait of a generation, has been overwhelming – garnering plundits such as ‘profound’, ‘celebratory’, ‘deeply moving’ – but, if this is the sum total of our response, are we not denying the power of art? Yes, there is much to celebrate here. Year 3 is an inherently hopeful statement: pick any school photo of seven-year-old children from across the world and you will experience the powerful looping effect of projection and reflection. Hairstyles and uniform policies may change, but those desperate grimaces and carefully choreographed seating arrangements remain the same. And, as McQueen has said, the photographs provide those kids with a rare and precious opportunity to step outside themselves, to see themselves through the eyes of others. On my various visits to Tate Britain the atmosphere was electrifying, with huge groups of children rushing around trying to find themselves.

One of the most exciting things about art – particularly art in the public realm – is that it exists within a precise political, social and environmental context. Year 3 was initially planned for 2012 to coincide with the Olympics at a time when the catastrophic results of the Conservative government’s austerity programme, established in 2010, had yet to kick-in. Yet 2019 presents an entirely different landscape, in which the fifth wealthiest country in the world has one of the highest rates of inequality, teachers are crowd-funding to buy toilet rolls and food for their pupils, schools are shutting early on Fridays because of a to lack of funds and support for children with special needs has been decimated. In today’s Britain, a child loses their home every eight minutes – that’s 183 children every day. The number of homeless children in London has risen by a third since 2014 and is now equivalent to one in every 24 children. This means that many of the photos in Year 3 include a child who is homeless. Add to all of this the impending climate catastrophe and the toxicity of Brexit, and we have a very different set of ‘hopeful futures’ for the majority of kids depicted here (Greta Thurnberg’s cutting words to the UN come to mind: ‘You all come to us young people for hope. How dare you’). What seems to be missing is the critical dimension that pervades the work and yet remains unspoken.

It should be acknowledged that Year 3 is an extremely valuable piece of social documentation and a call to arms. Here, on public display, we are witness to the extreme inequality present in the British education system which involves access to privilege for a select demographic attending private schools. We see differentiation according to race, religion and, most alarmingly, class sizes (imagine teaching 14 children rather than 30); our peculiar insistence that small children wear uniforms; and, finally, the telling gender imbalance of teachers – poorly paid, under-valued, overly reliant on unremunerated care: that’s women’s work.

Alongside the exhibition at Tate Britain, Artangel has mounted a selection of these class photos on billboards in the streets of London. This is where the rich, complex, knotty context of the public realm comes into play. What happens when you put a photo of one of those single-sex, blazered, 14-to-a-class cohorts (I would hazard a guess they are from a West London private school), on Barking High Street, in London’s most deprived borough? Can this still be touted as a glorious celebration of multicultural London?

It is salutary to acknowledge that if Year 3 was pitched as anything but a celebration, it is unlikely it would have received the considerable amount of funding required to bring it to fruition. In the run-up to the election, this project could plausibly be marketed as a Conservative Party stunt: ‘Everything’s fine – look, they’re smiling.’

Tate says the work is a hopeful portrait of children who will shape the future, but you could draw a circle around the small number of kids who will get a chance to shape that future. The artist says there is ‘an urgency to reflect on who we are’ – so let’s do just that. Let’s honour the work, and the next generation, with a meaningful discussion about those hopeful futures.

Cut Your Nose Like Your Hair

Art in the Public Sphere, Volume 7, Number 1, 2018

Play The City Now Or Never! Mobile App, Helen Stratford and Idit Nathan

Review

I often feel, when I am walking through the streets and shops of my hometown, that our enthusiastic embrace of consumerism and efficiency is pushing us further from ourselves. An old man attempting to use an automated till at the local post office finds the exchange not just technologically baffling but also physically and emotionally alienating. Where once there was a human exchange, a bit of banter, a light-hearted comment about inclement weather, now lies a mute machine that has no human characteristics resembling warmth, humour or engagement. Machines are obviously cheaper, and perhaps more efficient than people, but what does it mean for us when we strip out the bits of life that make us human?

When I leave the post office I walk down a street that, to most people’s eyes, is ‘public space’, owned and maintained by the council we pay our taxes to. But it’s not. It has been sold by the cash-strapped authorities to a private company that employs ‘street attendants’, and installs CCTV cameras to ensure that anybody who doesn’t fit a particular consumerist profile, who is seen loitering or taking photographs, or being curious, or even skipping, is asked to leave. In order to earn the right to inhabit this public space, we are required to engage in a financial transaction. Further up the street I see evidence of collusion between planners, developers and urban designers in the form of vicious looking spikes located in areas that might be used by homeless people to sleep in, or maybe by men looking for a place to piss at night.

None of this is particularly new, or even that interesting on first reading, but the implications are huge and potentially profoundly disturbing. The most visible outcome is an increase in social isolation and a sharp division between those who have, and those who don’t, while the less tangible effect (potentially more damaging in the long term) is the closing down of our psyches, the removal of a sense of physical and mental freedom to move beyond fixed codes of prescribed behaviour, to situate our bodies in public space and feel free to do with it what we want.

The last time we experienced this level of upheaval and significant change in ownership of the public realm was the Enclosures Acts of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Introduced by Parliament to increase productivity by limiting the number of commoners who had access to land, the Acts radically changed the psychological as well as physical landscape of the country. Land that was previously accessible to all was closed off, leaving a drastically reduced set of options available for people to feed their animals, fish and hunt, cultivate the land and escape their squalid living conditions. The Acts resulted in psychological scarring on a huge scale, constraining the human spirit and shutting down access to other worlds. On the face of it, this seems far more drastic than a few CCTV cameras and a polite request to move on. But what is so insidious about the situation as it stands today is that it is, for the most part, invisible. It forms a kind of low-level controlling hum that many of us are unaware of.

Artists Helen Stratford and Idit Nathan have been thinking about this low-level hum over the last couple of years, and the culmination of their research can be seen in the launch of a game called ‘Play the City Now or Never’ (PCNN). An App that can be downloaded onto a mobile ‘phone, the game is essentially a subversion tool to be used to reclaim the public realm. Rambling through the East Anglian streets of Peterborough or Southend, with movement linked to a GPS tracking device, participants are invited to carry out a number of site specific actions using a series of prompts: BALANCE WITH SOMEONE OR SOMETHING TO AVOID THE GRASS is located at a public seating area where the grass is out of bounds, and, looking out to sea, with the world’s longest pleasure pier within site: LISTEN TO THE RHYTHM OF THE WIND PLAYING THE MASTS. They are essentially absurdist actions that highlight the narrow parameters of society’s tolerance of what is deemed to be acceptable behaviour in public space. Stratford and Nathan devised a series of ‘walkshops’ with local people to elicit stories about places they have played, or would like to play; these stories have informed the prompts. DANCE THE MONKEY DRIFT is a reference to stories of ships’ monkeys being set adrift on planks of wood when sailors came ashore; DUCK DOWN TO AVOID CEDAR came out of a conversation with children about an enormous tree in Chalkwell Park that they hide in to escape from adults. With others, there is a more critical edge, where tolerance of privatisation and control wears thin: SKIP TO AVOID THE SECURITY STAFF IF YOU DARE and IMAGINE A PIER THAT IS FREE FOR ALL.

‘Play’, here, is being used as a tool to do a range of things from the prosaic to the sublime. Participants talk to each other and to strangers; they laugh (nervously and with abandon); make noise and disrupt; they notice things they’ve walked past every day; they embarrass other people (and themselves); they straddle, hop, sing, wave, skip and fall over. They are scurrilously re-writing the spatial etiquette rulebook and actively re-performing the spaces that they occupy on a daily basis; they are provoking those around them (the authorities, other members of the public, private companies) into joining in, retreating or even banishing them. At first glance, it seems light-hearted but it is deeply political. In the film that Stratford and Nathan have made documenting various participants at play, it is the groups of people who are often sidelined in society as well as mainstream politics and public life (women, older people, the disabled, young people) who form the majority of the players. These groups rely, disproportionally, on public realm provision, and the safety net provided by the Welfare State, and therefore have the most to lose from privatisation, commercialisation and the curtailment of the freedom associated with public life.

---------------------------

The twentieth century is rich with small-scale, radical, public interventions devised by artists to disrupt the status quo. There’s a thread of this type of activity that can be traced from Dada (1910s and 20s) to the Surrealists (1920s and 30s); the Situationist International (1950s and 60s), to performance art (1960s and 70s). All of these groups and artforms aimed, in some way, to transform participants into active agents, with many of them hoping for some kind of social and political change.

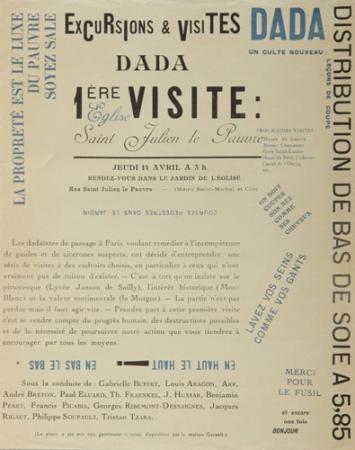

On 14 April 1921, members of the Dada movement in Paris launched ‘The Dada Season’ with a series of ‘excursions and visits’. The event was described by the artist George Hugnet as an ‘absurd rendezvous mimicking instructive walks’. Fliers were distributed to advertise the event which stated that artists wished to ‘set right the incompetence of suspicious guides’ and lead a series of ‘excursions and visits to places that have no reason to exist’. A series of demands were printed on the provocatively designed flyers: YOU SHOULD CUT YOUR NOSE LIKE YOUR HAIR and PROPERTY IS THE LUXURY OF THE POOR, BE DIRTY. By all accounts, it was a rather drab affair. It rained; hardly anyone came, and planned future visits never materialised.

The Situationist International, lead by the compelling, dictatorial and ultimately tragic, Guy Debord, promoted the idea that in order to repair the social bond we need to create an interface with reality through the art of interaction. Experimenting with the ‘construction of situations’ (hence their name), they made films, wrote books and devised street slogans. They expounded the importance of participation because it rehumanised a society ‘rendered numb and fragmented by the repressive instrumentality of capitalist production’. Two SI texts, Debord’s The Society of the Spectacle and Raoul Vaneigem’s The Revolution of Everyday Life were said to influence the student rebellion of 1968. Many of the slogans that were daubed onto Parisian walls were taken from these theses: FREE THE PASSIONS / NEVER WORK / LIVE WITHOUT DEAD TIME.

An arguably more revolutionary public act was carried out in the 1970s by the American artist Mierle Laderman Ukeles who launched a captivating, but also banal attack on entrenched value systems, encouraging people to act in order to change societal norms. For her public performance Touch Sanitation (1979–1980) she visited all fifty-nine sanitation districts in New York City to shake hands with, and thank, every one of the 8,500 sanitation workers for ‘keeping New York City alive’. At the end of her year–long performance she was elected Honorary Deputy Commissioner of Sanitation in NYC and Honorary Team Member of Local 831, United Sanitationmen’s Association. The performance was part of her Manifesto for Maintenance Art which she created in order to reveal the hidden, yet essential role of cleaning and maintenance work in Western society (a role often carried out by women in the home) and the radical implications of actively valuing it rather than hiding it from sight.

-----------------------

On the day I sat down to begin formulating thoughts about this text, my teenage son came running into my office, breathless with excitement: ‘Mum! I went to the park! It was amazing!’ He had discovered Pokémon Go, an augmented reality game which took the world by storm in the summer of 2016. It gets players out of their bedrooms into the streets, encourages them to discover new parts of their neighbourhood, and has become a catalyst for conversations amongst strangers. Players catch virtual creatures that live in public places (many in cultural centers, parks and near monuments); the more they collect, the more points they earn. It functions using a GPS tracking devise and a phone’s camera function, creating a two-tiered reality system that is both virtual and real. The game has resulted in the extraordinary spectacle of thousands of adults and children in a frenzied rush to catch rare Pokémons in the dead of night. Slightly more bizarrely, people have discovered dead bodies, been hit by cars and fallen off cliffs in their quest to acquire Pokémon Go acclaim.

On the surface, there seems to be many parallels between Pokémon Go and PCNN. A sense of adventure and discovery in outside spaces, as well as the element of social play, are perhaps the most obvious. But the sinister side of Pokémon Go is what interests me here, and can be linked to our culture of control, surveillance and commodification. In practical terms, all players of the game sign over access to data on their phone to the game’s owner (Nintendo), which can then be sold to a third party. This data is the currency of the twentyfirst century, and is linked to the way that the game is valued in the marketplace – it allows companies to build incredibly detailed profiles of millions of individuals, including information about where they shop, what they buy, what their interests are, what state their health is in, where they work etc. The aim is always to create targeted and sophisticated marketing campaigns to sell you things. Less tangibly, there’s also the issue that with Pokémon Go, the players’ imagination is activated for them. There is very little creativity, real freedom or lateral thought that comes into play when catching characters, fighting in ‘gyms’ or evolving into a more sophisticated species.

Inscribed within the Enclosures Acts and Pokémon Go is the concept of appropriation. In the former it is the visible, tangible public realm that is being appropriated, with the latter, it is our privacy. In Society of the Spectacle Guy Debord describes the effects that commodification and reification has on people stating that ‘The spectacle is an extension of the idea of reification where what was directly lived has moved away into a representation, all real relationships having been replaced by that of relationships with commodities, and where commodities have a life of their own – the autonomous movement of the non-living’. With PCNN there is no such appropriation, commodification, or hierarchy of ownership. It is designed to maximise certain degrees of freedom in the way it can be used. Players can explore all manner of worlds, including the idea of ‘publicness’; they can create their own publics with no sense that they are a vessel for corporate gain. Like projects and actions by the Dadaists, the SI and many performance artists, PCNN aims to ‘unplay the dominant systems of control’ and to re-inscribe power structures. In so doing, they create a platform for subtle interventions, political awakening and radical acts.

Notes

1.George Hugnet, L’aventure Dada, 1916-1922, Edition Seghers, 1971 (first published 1957). Translated and quoted in Claire Bishop’s Artificial Hells: Participatory Art and the Politics of Spectatorship, London: Verso, 2012

2.Claire Bishop, Artificial Hells: Participatory Art and the Politics of Spectatorship, London: Verso, 2012

3. Guy Debord, Society of the Spectacle, Detroit: Black & Red, 1970

4.Mary Flanagan, Critical Play: Radical Game Design, MIT Press, 2009

Review

I often feel, when I am walking through the streets and shops of my hometown, that our enthusiastic embrace of consumerism and efficiency is pushing us further from ourselves. An old man attempting to use an automated till at the local post office finds the exchange not just technologically baffling but also physically and emotionally alienating. Where once there was a human exchange, a bit of banter, a light-hearted comment about inclement weather, now lies a mute machine that has no human characteristics resembling warmth, humour or engagement. Machines are obviously cheaper, and perhaps more efficient than people, but what does it mean for us when we strip out the bits of life that make us human?

When I leave the post office I walk down a street that, to most people’s eyes, is ‘public space’, owned and maintained by the council we pay our taxes to. But it’s not. It has been sold by the cash-strapped authorities to a private company that employs ‘street attendants’, and installs CCTV cameras to ensure that anybody who doesn’t fit a particular consumerist profile, who is seen loitering or taking photographs, or being curious, or even skipping, is asked to leave. In order to earn the right to inhabit this public space, we are required to engage in a financial transaction. Further up the street I see evidence of collusion between planners, developers and urban designers in the form of vicious looking spikes located in areas that might be used by homeless people to sleep in, or maybe by men looking for a place to piss at night.

None of this is particularly new, or even that interesting on first reading, but the implications are huge and potentially profoundly disturbing. The most visible outcome is an increase in social isolation and a sharp division between those who have, and those who don’t, while the less tangible effect (potentially more damaging in the long term) is the closing down of our psyches, the removal of a sense of physical and mental freedom to move beyond fixed codes of prescribed behaviour, to situate our bodies in public space and feel free to do with it what we want.

The last time we experienced this level of upheaval and significant change in ownership of the public realm was the Enclosures Acts of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Introduced by Parliament to increase productivity by limiting the number of commoners who had access to land, the Acts radically changed the psychological as well as physical landscape of the country. Land that was previously accessible to all was closed off, leaving a drastically reduced set of options available for people to feed their animals, fish and hunt, cultivate the land and escape their squalid living conditions. The Acts resulted in psychological scarring on a huge scale, constraining the human spirit and shutting down access to other worlds. On the face of it, this seems far more drastic than a few CCTV cameras and a polite request to move on. But what is so insidious about the situation as it stands today is that it is, for the most part, invisible. It forms a kind of low-level controlling hum that many of us are unaware of.

Artists Helen Stratford and Idit Nathan have been thinking about this low-level hum over the last couple of years, and the culmination of their research can be seen in the launch of a game called ‘Play the City Now or Never’ (PCNN). An App that can be downloaded onto a mobile ‘phone, the game is essentially a subversion tool to be used to reclaim the public realm. Rambling through the East Anglian streets of Peterborough or Southend, with movement linked to a GPS tracking device, participants are invited to carry out a number of site specific actions using a series of prompts: BALANCE WITH SOMEONE OR SOMETHING TO AVOID THE GRASS is located at a public seating area where the grass is out of bounds, and, looking out to sea, with the world’s longest pleasure pier within site: LISTEN TO THE RHYTHM OF THE WIND PLAYING THE MASTS. They are essentially absurdist actions that highlight the narrow parameters of society’s tolerance of what is deemed to be acceptable behaviour in public space. Stratford and Nathan devised a series of ‘walkshops’ with local people to elicit stories about places they have played, or would like to play; these stories have informed the prompts. DANCE THE MONKEY DRIFT is a reference to stories of ships’ monkeys being set adrift on planks of wood when sailors came ashore; DUCK DOWN TO AVOID CEDAR came out of a conversation with children about an enormous tree in Chalkwell Park that they hide in to escape from adults. With others, there is a more critical edge, where tolerance of privatisation and control wears thin: SKIP TO AVOID THE SECURITY STAFF IF YOU DARE and IMAGINE A PIER THAT IS FREE FOR ALL.

‘Play’, here, is being used as a tool to do a range of things from the prosaic to the sublime. Participants talk to each other and to strangers; they laugh (nervously and with abandon); make noise and disrupt; they notice things they’ve walked past every day; they embarrass other people (and themselves); they straddle, hop, sing, wave, skip and fall over. They are scurrilously re-writing the spatial etiquette rulebook and actively re-performing the spaces that they occupy on a daily basis; they are provoking those around them (the authorities, other members of the public, private companies) into joining in, retreating or even banishing them. At first glance, it seems light-hearted but it is deeply political. In the film that Stratford and Nathan have made documenting various participants at play, it is the groups of people who are often sidelined in society as well as mainstream politics and public life (women, older people, the disabled, young people) who form the majority of the players. These groups rely, disproportionally, on public realm provision, and the safety net provided by the Welfare State, and therefore have the most to lose from privatisation, commercialisation and the curtailment of the freedom associated with public life.

---------------------------

The twentieth century is rich with small-scale, radical, public interventions devised by artists to disrupt the status quo. There’s a thread of this type of activity that can be traced from Dada (1910s and 20s) to the Surrealists (1920s and 30s); the Situationist International (1950s and 60s), to performance art (1960s and 70s). All of these groups and artforms aimed, in some way, to transform participants into active agents, with many of them hoping for some kind of social and political change.

On 14 April 1921, members of the Dada movement in Paris launched ‘The Dada Season’ with a series of ‘excursions and visits’. The event was described by the artist George Hugnet as an ‘absurd rendezvous mimicking instructive walks’. Fliers were distributed to advertise the event which stated that artists wished to ‘set right the incompetence of suspicious guides’ and lead a series of ‘excursions and visits to places that have no reason to exist’. A series of demands were printed on the provocatively designed flyers: YOU SHOULD CUT YOUR NOSE LIKE YOUR HAIR and PROPERTY IS THE LUXURY OF THE POOR, BE DIRTY. By all accounts, it was a rather drab affair. It rained; hardly anyone came, and planned future visits never materialised.

The Situationist International, lead by the compelling, dictatorial and ultimately tragic, Guy Debord, promoted the idea that in order to repair the social bond we need to create an interface with reality through the art of interaction. Experimenting with the ‘construction of situations’ (hence their name), they made films, wrote books and devised street slogans. They expounded the importance of participation because it rehumanised a society ‘rendered numb and fragmented by the repressive instrumentality of capitalist production’. Two SI texts, Debord’s The Society of the Spectacle and Raoul Vaneigem’s The Revolution of Everyday Life were said to influence the student rebellion of 1968. Many of the slogans that were daubed onto Parisian walls were taken from these theses: FREE THE PASSIONS / NEVER WORK / LIVE WITHOUT DEAD TIME.

An arguably more revolutionary public act was carried out in the 1970s by the American artist Mierle Laderman Ukeles who launched a captivating, but also banal attack on entrenched value systems, encouraging people to act in order to change societal norms. For her public performance Touch Sanitation (1979–1980) she visited all fifty-nine sanitation districts in New York City to shake hands with, and thank, every one of the 8,500 sanitation workers for ‘keeping New York City alive’. At the end of her year–long performance she was elected Honorary Deputy Commissioner of Sanitation in NYC and Honorary Team Member of Local 831, United Sanitationmen’s Association. The performance was part of her Manifesto for Maintenance Art which she created in order to reveal the hidden, yet essential role of cleaning and maintenance work in Western society (a role often carried out by women in the home) and the radical implications of actively valuing it rather than hiding it from sight.

-----------------------

On the day I sat down to begin formulating thoughts about this text, my teenage son came running into my office, breathless with excitement: ‘Mum! I went to the park! It was amazing!’ He had discovered Pokémon Go, an augmented reality game which took the world by storm in the summer of 2016. It gets players out of their bedrooms into the streets, encourages them to discover new parts of their neighbourhood, and has become a catalyst for conversations amongst strangers. Players catch virtual creatures that live in public places (many in cultural centers, parks and near monuments); the more they collect, the more points they earn. It functions using a GPS tracking devise and a phone’s camera function, creating a two-tiered reality system that is both virtual and real. The game has resulted in the extraordinary spectacle of thousands of adults and children in a frenzied rush to catch rare Pokémons in the dead of night. Slightly more bizarrely, people have discovered dead bodies, been hit by cars and fallen off cliffs in their quest to acquire Pokémon Go acclaim.

On the surface, there seems to be many parallels between Pokémon Go and PCNN. A sense of adventure and discovery in outside spaces, as well as the element of social play, are perhaps the most obvious. But the sinister side of Pokémon Go is what interests me here, and can be linked to our culture of control, surveillance and commodification. In practical terms, all players of the game sign over access to data on their phone to the game’s owner (Nintendo), which can then be sold to a third party. This data is the currency of the twentyfirst century, and is linked to the way that the game is valued in the marketplace – it allows companies to build incredibly detailed profiles of millions of individuals, including information about where they shop, what they buy, what their interests are, what state their health is in, where they work etc. The aim is always to create targeted and sophisticated marketing campaigns to sell you things. Less tangibly, there’s also the issue that with Pokémon Go, the players’ imagination is activated for them. There is very little creativity, real freedom or lateral thought that comes into play when catching characters, fighting in ‘gyms’ or evolving into a more sophisticated species.

Inscribed within the Enclosures Acts and Pokémon Go is the concept of appropriation. In the former it is the visible, tangible public realm that is being appropriated, with the latter, it is our privacy. In Society of the Spectacle Guy Debord describes the effects that commodification and reification has on people stating that ‘The spectacle is an extension of the idea of reification where what was directly lived has moved away into a representation, all real relationships having been replaced by that of relationships with commodities, and where commodities have a life of their own – the autonomous movement of the non-living’. With PCNN there is no such appropriation, commodification, or hierarchy of ownership. It is designed to maximise certain degrees of freedom in the way it can be used. Players can explore all manner of worlds, including the idea of ‘publicness’; they can create their own publics with no sense that they are a vessel for corporate gain. Like projects and actions by the Dadaists, the SI and many performance artists, PCNN aims to ‘unplay the dominant systems of control’ and to re-inscribe power structures. In so doing, they create a platform for subtle interventions, political awakening and radical acts.

Notes

1.George Hugnet, L’aventure Dada, 1916-1922, Edition Seghers, 1971 (first published 1957). Translated and quoted in Claire Bishop’s Artificial Hells: Participatory Art and the Politics of Spectatorship, London: Verso, 2012

2.Claire Bishop, Artificial Hells: Participatory Art and the Politics of Spectatorship, London: Verso, 2012

3. Guy Debord, Society of the Spectacle, Detroit: Black & Red, 1970

4.Mary Flanagan, Critical Play: Radical Game Design, MIT Press, 2009

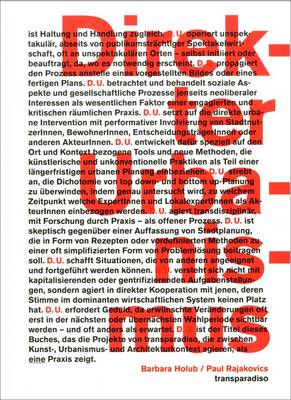

Direct Urbanism, Transparadiso: Barbara Holub and Paul Rajakovics

Art & the Public Sphere, Volume 3 Number 1 2015

Book review

Direct Urbanism, Transparadiso: Barbara Holub and Paul Rajakovics (2013)

Authors: Jane Rendell, Paul O'Neil, Mick Wilson

Verlag fur Moderne Kunst, (216 pp.), colour illustrations

ISBN-10: 3869844086

Language: English, German, Softcover

Jes Fernie, independent curator

Over the past fifteen years there has been a noticeable, if small, increase in the number of newly established practices that are exploring alternative approaches to urban issues, drawing on the work of theorists and artist groups such as the Situationists. But these practices often follow one of two distinct paths: those that drop the experimental work when 'real' buildings start to enter the frame, and those who immerse themselves in academia where they are more able to assume a critical, theoretical approach. It's clear that this type of fracturing is dangerous as it leaves both worlds devoid of a crucial component which ultimately impacts on the quality of our lived experience in the public realm.

Those practices that have stuck to their original convictions, developing a body of work that explicitly addresses messy social, political and environmental issues, as well as embracing a dialogue with other disciplines such as art, are few and far between. In the UK, there's muf, a practice developed by Liza Fior and Katherine Clark in the mid 90s which has managed, against significant odds, to gain a reputation for drawing out a more nuanced range of possibilities for public life, including space for play, conversation, and engagement of the human spirit, all within the unforgiving framework of the UK planning system.

Another practice that has managed to sustain this type of work is Transparadiso, an art / architecture group based in Vienna established by Barbara Holub and Paul Rajakovics. It was established in 1999 as a response to the a-critical stance that architectural practices seemed to be taking in relation to the market-based economy of excess that came out of the 1980s, flourished in the 90s and has firmly taken root in 21st century. Holub and Rajakovics became convinced that a radical change was needed, and that the active involvement of the user was crucial to the success of any architectural or urban planning project. This was best achieved, they insisted, through the pursuit of a utopia beyond the rigid framework of existing professions. Different disciplines such as art, architecture, sociology and urban planning should come together to create a more viable, rich experience of public and private space.

During the period that Transparadiso has existed, the rhetoric around 'participation' and the co-opting of artists and cultural practitioners to re-design neglected urban spaces has expanded ten fold. Holub and Rajakovics are unsurprisingly skeptical about this move by capital and neoliberal strategists, but what sets them apart is their willingness to engage with developers and clients who have vested interests in this system. Rather than employing an antagonistic approach to complex situations, they will, for example, conceive of a game which generates discussion about a set of issues experienced by a particular group of local people. The aim is to plant the seed for long-term engagement in issues associated with urban planning and its direct effects on people's lives, thereby creating more politically astute and demanding citizens.

Like other practices of its ilk, Transparadiso questions the dominant model of sole author as creator of an original idea, a model upheld by many star architects across the globe. When Holub was starting her career working for other architects she became aware of the construct of the 'master' architect in a male-dominated field, who was compliant with politicians' interests and fitted nicely into the clients' view of what an architect should be. Transparadiso's rostrum of projects is a clear rejection of this model. While Holub and Rajakovics don't shy away from making uncomfortable decisions and sticking their neck out where they needn't, there is always a sense in their projects of a conversation in which users, client and architect are building a project together, rather than a hierarchical one in which an impressionistic sketch by the star at the top is realised by the minions below.

Over the past fifteen years Transparadiso has carried out a beguiling array of projects that sets them apart from almost all of their peers. A snapshot of their practice includes a haptically sensual living room for residents of a hospice; the staging of a dinner party for local people in a gallery which questioned the dramatic rise in the corporatisation of the art world; a performative deconstruction of Kennedy's 'Ich bin win Berliner' declaration with an African American twist; and a large-scale urban realm project involving apartment blocks, retail units and public domain spaces. Direct Urbanism brings all of Transparadiso's projects together and positions them within the broader framework of the practice's conceptual oeuvre, but more importantly, the book constitutes a provocation to other architects, artists, planners and members of the public to play a part in overhauling a rotten and malfunctioning system.

Practices of this type are notoriously hard to relay in photographic form. The 'thing' that we are being asked to focus on is very rarely the end product but a process of dialogue, including dead-ends and other moments that aren't easily captured within the pages of a book. The first impression of Direct Urbanism, as it is flicked through, is in direct contrast to the experience of reading it. Dry architectural drawings, models and plans are accompanied by small photographs of participatory workshops and social situations (the curse of many publications that attempt to document socially engaged practice). The designer has done a good with the available material (particularly since it is dual language text - German and English), but the seduction for me lies in the text rather than the images.

The book is divided into three sections: Urban practices, interventions and tools; Architecture & urbanism; and Urbanism and art, all of which sound pretty amorphous until you get to the pieces of text within these sections which take on a distinct language of their own. An interview between the members of Transparadiso and a curator (Paul O'Neill) and artist / teacher (Mick Wilson) which takes a selection of their projects to draw out the philosophy of the practice, is followed by a piece of experimental text by architectural theorist Jane Rendell, which plays with the prepositions in Transparadiso's name ('trans' and 'para') through a trivalent essay. The final text is a manifesto of sorts by Holub and Rajakovics in which they set out their stall.

It's a rather fantastic combination of texts from a diverse range of voices which clearly reflects Transparadiso's interest in creating lines of thought that lead from one world to the next. And, against all the odds, it works. At moments it is genuinely exciting, and the possibilities for assuming such an approach become very real. What if we lived in a world where words like 'ambivalence', 'disruption' and 'desire' were used in the urban planning system? Wouldn't it be great if more architects worked at the interface of politics, culture, life and architecture? And how much better would civic life be if citizens were engaged in conversations about where and how we live?

The title of the book is a direct reference to Guy Debord's concept of 'unitary urbanism', a theory of 'combined use of arts and techniques for the integral construction of a milieu in dynamic relation with experiments in behaviour'. It also nods to the dichotomy of tactics (direct) and strategy (urbanism as city planning) found in the writings of Michel de Certeau. As Holub and Rajakovics point out in their manifesto at the end of the book: 'By uniting 'tactics and 'strategy'… we have attempted to overcome this dichotomy'.

The commitment by Transparadiso to a broader social good, as well as a rigorous intellectual programme, is undeniable. However, if this book is primarily about encouraging non-specialists to take part in a dialogue about urban spaces and planning, where is this voice and what is its legacy? Who is to say any of these projects have been a 'success' in the eyes of the participants? In projects such as Commons come to Liezen, for example, Transparadiso installed a pavilion in a public garden which included a large scale Tangram game (a dissection puzzle) that engaged residents in a discussion about art as a space for reflection and action in their neighbourhood. How was this project received and did it manage to wind its way into public consciousness? It would be good too, to read about what the residents of Stadwerk Lehen (an ambitious housing scheme on the outskirts of Salzburg) think about their experience of living in an environment that was designed to position the user at its heart. A raft of thoughtful acts were carried out by Transparadiso to help tackle issues relating to social isolation and access to a public voice: a sociologist was invited onto the steering committee to help guide the project; specific designs were implemented for single parents, homes with children and communal areas; a subsidy was brokered for the public ground floor buildings which are inhabited by not for profit organisations (including a contemporary art gallery); and connections were made to link the area to adjacent parts of Salzburg in order to combat community isolation. Did all of this 'work'? What didn't?

Many architects, planners and urban thinkers will view this type of practice as desirable but economically unviable. Reading through the précis's of each project, the reader gets a clear sense of the considerable amount of personal and emotional commitment, as well as on-the-ground physical presence, that projects of this type require. Many practices that start out with socially-engaged manifestos are unable to sustain the model beyond their initial, youthful years, when they have the energy and time to commit to such schemes. If this type of model were to be rolled out on a grander scale, the processes of procurement, realisation and community liaison would have to be radically restructured, particularly in relation to remuneration for design team members.

And then there is the loaded question regarding the 'duty' of the architect - the moralistic overtones of which are implicitly rejected by many architectural and urban design practices. Is it the duty of architects to consider social and political issues as well as formal, logistical and economic ones? Holub and Rajakovics are explicit about this and state in the book that they are a 'transdiciplinary practice that considers architecture, urban planning and art a responsibility towards society'. This subject has recently had a public airing with Richard Roger's statement on the eve of the opening of his exhibition at The Royal Academy last year that 'architecture's civic responsibility has been eroded in "an age of greed"'. Clearly, the conversation needs to continue.

What's exciting about this book is that it takes a series of disparate subjects (Situationism, socially engaged practice, architecture and urban planning policy) and links them together in a way that is both beguiling and practical.

It is wonderful to consider what might be possible if only this type of practice wasn't the exception but the rule. The book highlights the woeful limitations of much architecture, urban design and the planning system, as well as broader issues such as structural inequality and encroaching neo-liberalism. At a time when societal responsibility and the welfare state are being slowly dismantled, Transparadiso's approach is not just desirable but critical.

Jes Fernie

April 2015

Notes

'This is what we do: a muf manual', Ellipsis, 2001

See Site-Writing, The Architecture of Art Criticism, Jane Rendell, I B Tauris, 2010Situationistische Internationale 1957 - 72, Museum moderner Kunst 1988

Michel de Ceteau, The Practice of Every Day Life, 1980

Dezeen Book of Interviews, May 2014, publisher: Dezeen Ltd

Direct Urbanism, Transparadiso: Barbara Holub and Paul Rajakovics (2013)

Authors: Jane Rendell, Paul O'Neil, Mick Wilson

Verlag fur Moderne Kunst, (216 pp.), colour illustrations

ISBN-10: 3869844086

Language: English, German, Softcover

Jes Fernie, independent curator

Over the past fifteen years there has been a noticeable, if small, increase in the number of newly established practices that are exploring alternative approaches to urban issues, drawing on the work of theorists and artist groups such as the Situationists. But these practices often follow one of two distinct paths: those that drop the experimental work when 'real' buildings start to enter the frame, and those who immerse themselves in academia where they are more able to assume a critical, theoretical approach. It's clear that this type of fracturing is dangerous as it leaves both worlds devoid of a crucial component which ultimately impacts on the quality of our lived experience in the public realm.

Those practices that have stuck to their original convictions, developing a body of work that explicitly addresses messy social, political and environmental issues, as well as embracing a dialogue with other disciplines such as art, are few and far between. In the UK, there's muf, a practice developed by Liza Fior and Katherine Clark in the mid 90s which has managed, against significant odds, to gain a reputation for drawing out a more nuanced range of possibilities for public life, including space for play, conversation, and engagement of the human spirit, all within the unforgiving framework of the UK planning system.

Another practice that has managed to sustain this type of work is Transparadiso, an art / architecture group based in Vienna established by Barbara Holub and Paul Rajakovics. It was established in 1999 as a response to the a-critical stance that architectural practices seemed to be taking in relation to the market-based economy of excess that came out of the 1980s, flourished in the 90s and has firmly taken root in 21st century. Holub and Rajakovics became convinced that a radical change was needed, and that the active involvement of the user was crucial to the success of any architectural or urban planning project. This was best achieved, they insisted, through the pursuit of a utopia beyond the rigid framework of existing professions. Different disciplines such as art, architecture, sociology and urban planning should come together to create a more viable, rich experience of public and private space.

During the period that Transparadiso has existed, the rhetoric around 'participation' and the co-opting of artists and cultural practitioners to re-design neglected urban spaces has expanded ten fold. Holub and Rajakovics are unsurprisingly skeptical about this move by capital and neoliberal strategists, but what sets them apart is their willingness to engage with developers and clients who have vested interests in this system. Rather than employing an antagonistic approach to complex situations, they will, for example, conceive of a game which generates discussion about a set of issues experienced by a particular group of local people. The aim is to plant the seed for long-term engagement in issues associated with urban planning and its direct effects on people's lives, thereby creating more politically astute and demanding citizens.

Like other practices of its ilk, Transparadiso questions the dominant model of sole author as creator of an original idea, a model upheld by many star architects across the globe. When Holub was starting her career working for other architects she became aware of the construct of the 'master' architect in a male-dominated field, who was compliant with politicians' interests and fitted nicely into the clients' view of what an architect should be. Transparadiso's rostrum of projects is a clear rejection of this model. While Holub and Rajakovics don't shy away from making uncomfortable decisions and sticking their neck out where they needn't, there is always a sense in their projects of a conversation in which users, client and architect are building a project together, rather than a hierarchical one in which an impressionistic sketch by the star at the top is realised by the minions below.

Over the past fifteen years Transparadiso has carried out a beguiling array of projects that sets them apart from almost all of their peers. A snapshot of their practice includes a haptically sensual living room for residents of a hospice; the staging of a dinner party for local people in a gallery which questioned the dramatic rise in the corporatisation of the art world; a performative deconstruction of Kennedy's 'Ich bin win Berliner' declaration with an African American twist; and a large-scale urban realm project involving apartment blocks, retail units and public domain spaces. Direct Urbanism brings all of Transparadiso's projects together and positions them within the broader framework of the practice's conceptual oeuvre, but more importantly, the book constitutes a provocation to other architects, artists, planners and members of the public to play a part in overhauling a rotten and malfunctioning system.

Practices of this type are notoriously hard to relay in photographic form. The 'thing' that we are being asked to focus on is very rarely the end product but a process of dialogue, including dead-ends and other moments that aren't easily captured within the pages of a book. The first impression of Direct Urbanism, as it is flicked through, is in direct contrast to the experience of reading it. Dry architectural drawings, models and plans are accompanied by small photographs of participatory workshops and social situations (the curse of many publications that attempt to document socially engaged practice). The designer has done a good with the available material (particularly since it is dual language text - German and English), but the seduction for me lies in the text rather than the images.

The book is divided into three sections: Urban practices, interventions and tools; Architecture & urbanism; and Urbanism and art, all of which sound pretty amorphous until you get to the pieces of text within these sections which take on a distinct language of their own. An interview between the members of Transparadiso and a curator (Paul O'Neill) and artist / teacher (Mick Wilson) which takes a selection of their projects to draw out the philosophy of the practice, is followed by a piece of experimental text by architectural theorist Jane Rendell, which plays with the prepositions in Transparadiso's name ('trans' and 'para') through a trivalent essay. The final text is a manifesto of sorts by Holub and Rajakovics in which they set out their stall.

It's a rather fantastic combination of texts from a diverse range of voices which clearly reflects Transparadiso's interest in creating lines of thought that lead from one world to the next. And, against all the odds, it works. At moments it is genuinely exciting, and the possibilities for assuming such an approach become very real. What if we lived in a world where words like 'ambivalence', 'disruption' and 'desire' were used in the urban planning system? Wouldn't it be great if more architects worked at the interface of politics, culture, life and architecture? And how much better would civic life be if citizens were engaged in conversations about where and how we live?

The title of the book is a direct reference to Guy Debord's concept of 'unitary urbanism', a theory of 'combined use of arts and techniques for the integral construction of a milieu in dynamic relation with experiments in behaviour'. It also nods to the dichotomy of tactics (direct) and strategy (urbanism as city planning) found in the writings of Michel de Certeau. As Holub and Rajakovics point out in their manifesto at the end of the book: 'By uniting 'tactics and 'strategy'… we have attempted to overcome this dichotomy'.

The commitment by Transparadiso to a broader social good, as well as a rigorous intellectual programme, is undeniable. However, if this book is primarily about encouraging non-specialists to take part in a dialogue about urban spaces and planning, where is this voice and what is its legacy? Who is to say any of these projects have been a 'success' in the eyes of the participants? In projects such as Commons come to Liezen, for example, Transparadiso installed a pavilion in a public garden which included a large scale Tangram game (a dissection puzzle) that engaged residents in a discussion about art as a space for reflection and action in their neighbourhood. How was this project received and did it manage to wind its way into public consciousness? It would be good too, to read about what the residents of Stadwerk Lehen (an ambitious housing scheme on the outskirts of Salzburg) think about their experience of living in an environment that was designed to position the user at its heart. A raft of thoughtful acts were carried out by Transparadiso to help tackle issues relating to social isolation and access to a public voice: a sociologist was invited onto the steering committee to help guide the project; specific designs were implemented for single parents, homes with children and communal areas; a subsidy was brokered for the public ground floor buildings which are inhabited by not for profit organisations (including a contemporary art gallery); and connections were made to link the area to adjacent parts of Salzburg in order to combat community isolation. Did all of this 'work'? What didn't?

Many architects, planners and urban thinkers will view this type of practice as desirable but economically unviable. Reading through the précis's of each project, the reader gets a clear sense of the considerable amount of personal and emotional commitment, as well as on-the-ground physical presence, that projects of this type require. Many practices that start out with socially-engaged manifestos are unable to sustain the model beyond their initial, youthful years, when they have the energy and time to commit to such schemes. If this type of model were to be rolled out on a grander scale, the processes of procurement, realisation and community liaison would have to be radically restructured, particularly in relation to remuneration for design team members.

And then there is the loaded question regarding the 'duty' of the architect - the moralistic overtones of which are implicitly rejected by many architectural and urban design practices. Is it the duty of architects to consider social and political issues as well as formal, logistical and economic ones? Holub and Rajakovics are explicit about this and state in the book that they are a 'transdiciplinary practice that considers architecture, urban planning and art a responsibility towards society'. This subject has recently had a public airing with Richard Roger's statement on the eve of the opening of his exhibition at The Royal Academy last year that 'architecture's civic responsibility has been eroded in "an age of greed"'. Clearly, the conversation needs to continue.

What's exciting about this book is that it takes a series of disparate subjects (Situationism, socially engaged practice, architecture and urban planning policy) and links them together in a way that is both beguiling and practical.

It is wonderful to consider what might be possible if only this type of practice wasn't the exception but the rule. The book highlights the woeful limitations of much architecture, urban design and the planning system, as well as broader issues such as structural inequality and encroaching neo-liberalism. At a time when societal responsibility and the welfare state are being slowly dismantled, Transparadiso's approach is not just desirable but critical.

Jes Fernie

April 2015

Notes

'This is what we do: a muf manual', Ellipsis, 2001

See Site-Writing, The Architecture of Art Criticism, Jane Rendell, I B Tauris, 2010Situationistische Internationale 1957 - 72, Museum moderner Kunst 1988

Michel de Ceteau, The Practice of Every Day Life, 1980

Dezeen Book of Interviews, May 2014, publisher: Dezeen Ltd

Art & Arcitecture: A Place Inbetween

RIBA Journal, February 2007. Book published by I B Tauris

Art located in the public domain has been called all sorts of things since its rapid growth in the 1970's, many with scatological overtones: 'site-specific art', 'plop art', 'public art' and 'turds in the plaza'. In her new book Art and Architecture: A Place Between Jane Rendell proposes that we give it a new name: 'critical spatial practice'. Using the work of 'spatial thinkers' such as Walter Benjamin, Doreen Massy and Michel de Certeau, Rendell forms the argument that this term allows us to engage with the social and the aesthetic, the public and the private, whilst also highlighting the importance of the critical and spatial aspects of interdisciplinary practice.

In my view, the dearth of in-depth critical analysis of art in the public domain is symptomatic of the gap that exists between critical thinking in the fields of art on the one hand and architecture on the other. With its analysis of key issues such as the increasingly important role that relationships between people play in the production and occupation of art and architecture, as well as the tricky ground that is to be negotiated between the terms 'site', 'non-site' and 'off-site', this book goes some way to rectify this.

Rendell has borrowed three concepts of 'space', 'time' and 'social being' devised by the postmodern geographer Edward W Soja to organise her book into three sections: Between Here and There; Between Now and Then; Between One and Another. This division serves her purpose well and provides a sturdy hanger on which to drape her argument. In 'Between Here and There' she looks at the current vogue for locating work outside the gallery domain and addresses the sensitive issue of accessibility: do the growing number of off-site projects and biennials merely reinforce the institutional boundaries set up by galleries? Is the 'expanded field' (a phrase coined by critic Rosalind Krauss in 1979 to refer to the work of land artists) best understood in terms of site, place or space? And can we use the terms 'space', 'place', and 'site' to refer to different processes involved in critical spatial practice?

'Between Now and Then' focuses on the fascination that many current artists and architects have for buildings and sites that are derelict or abandoned. An investigation into the way 'inappropriate' materials and languages are used to displace dominant meanings and interrupt particular contexts is highlighted through examples ranging from Conford & Cross' intervention into Norman Foster's Sainsbury Centre for the Visual Arts in Norwich, and Sarah Wigglesworth's Staw Bale House in London.

The last section, 'Between One and Another' is a rather more whimsical plea for artworks to be considered less as a set of 'things' or 'objects' than as a series of exchanges that take place between people through such processes as collaboration, social sculpture and walking. Rendell uses the analogy of a preposition in a sentence to highlight how art facilitates connections between people. 'I offer tea 'to' you, in return, you offer me something from your pocket. As vehicles for interpersonal exchange, prepositions, in this case the tea bags, provide the potential for transformation; through a simple conversation… there is always the possibility we might change and rethink the position we occupy in the world.' This potential for art to change fundamental viewpoints is discussed through the work of Mierle Laderman Ukeles whose seminal work 'Manifesto for Maintenance Art' (1969) existed in a place between art and society: in the forming of relationships with the 8,500 rubbish collectors of New York through repeated ceremonial handshakes, in recognition of the role they play in maintaining the fabric of the city.

When asked how he positioned his publicly sited works, the American artist Chris Burden said recently: 'I just make art. Public art is something else, I'm not sure it's art. I think it's about a social agenda'. Whilst I take issue with Burden's refusal to engage with the political, social or even critical matters involved in siting his art in the public domain, my inclination is to go along with the idea that to make a distinction between gallery and non-gallery art is problematic. Rendell proposes we give 'public art' a new name; I take the view that we should abolish it altogether, acknowledging that every site (indoors or outdoors) is loaded with some sort of meaning. The extremely well researched and considered arguments in this book have made me rethink my position. It would be easy to dismiss Art and Architecture as overly academic (it is) and unrealistic (it is) but it is important to recognise that Rendell's attempt to lay the foundations for a new form of practice is genuinely exploratory and significant.

In my view, the dearth of in-depth critical analysis of art in the public domain is symptomatic of the gap that exists between critical thinking in the fields of art on the one hand and architecture on the other. With its analysis of key issues such as the increasingly important role that relationships between people play in the production and occupation of art and architecture, as well as the tricky ground that is to be negotiated between the terms 'site', 'non-site' and 'off-site', this book goes some way to rectify this.

Rendell has borrowed three concepts of 'space', 'time' and 'social being' devised by the postmodern geographer Edward W Soja to organise her book into three sections: Between Here and There; Between Now and Then; Between One and Another. This division serves her purpose well and provides a sturdy hanger on which to drape her argument. In 'Between Here and There' she looks at the current vogue for locating work outside the gallery domain and addresses the sensitive issue of accessibility: do the growing number of off-site projects and biennials merely reinforce the institutional boundaries set up by galleries? Is the 'expanded field' (a phrase coined by critic Rosalind Krauss in 1979 to refer to the work of land artists) best understood in terms of site, place or space? And can we use the terms 'space', 'place', and 'site' to refer to different processes involved in critical spatial practice?

'Between Now and Then' focuses on the fascination that many current artists and architects have for buildings and sites that are derelict or abandoned. An investigation into the way 'inappropriate' materials and languages are used to displace dominant meanings and interrupt particular contexts is highlighted through examples ranging from Conford & Cross' intervention into Norman Foster's Sainsbury Centre for the Visual Arts in Norwich, and Sarah Wigglesworth's Staw Bale House in London.

The last section, 'Between One and Another' is a rather more whimsical plea for artworks to be considered less as a set of 'things' or 'objects' than as a series of exchanges that take place between people through such processes as collaboration, social sculpture and walking. Rendell uses the analogy of a preposition in a sentence to highlight how art facilitates connections between people. 'I offer tea 'to' you, in return, you offer me something from your pocket. As vehicles for interpersonal exchange, prepositions, in this case the tea bags, provide the potential for transformation; through a simple conversation… there is always the possibility we might change and rethink the position we occupy in the world.' This potential for art to change fundamental viewpoints is discussed through the work of Mierle Laderman Ukeles whose seminal work 'Manifesto for Maintenance Art' (1969) existed in a place between art and society: in the forming of relationships with the 8,500 rubbish collectors of New York through repeated ceremonial handshakes, in recognition of the role they play in maintaining the fabric of the city.

When asked how he positioned his publicly sited works, the American artist Chris Burden said recently: 'I just make art. Public art is something else, I'm not sure it's art. I think it's about a social agenda'. Whilst I take issue with Burden's refusal to engage with the political, social or even critical matters involved in siting his art in the public domain, my inclination is to go along with the idea that to make a distinction between gallery and non-gallery art is problematic. Rendell proposes we give 'public art' a new name; I take the view that we should abolish it altogether, acknowledging that every site (indoors or outdoors) is loaded with some sort of meaning. The extremely well researched and considered arguments in this book have made me rethink my position. It would be easy to dismiss Art and Architecture as overly academic (it is) and unrealistic (it is) but it is important to recognise that Rendell's attempt to lay the foundations for a new form of practice is genuinely exploratory and significant.

Elmgreen & Dragset: The Welfare Show

Review of exhibition at Serpentine Gallery, Icon, April 2006