Writing / Essays

Our most basic, sophisticated selves

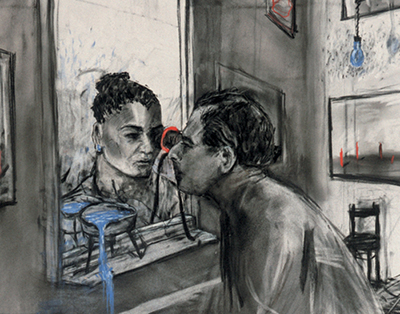

Exhibition text for Sarah Ryder's exhibition 'Multiferals' at Exeter Phoenix Gallery. Published by Exeter Phoenix, 2025

I often think about how sculptures are stored. They take up so much space and the people who make them often don’t have the funds to house them. They spend most of their lives in blind darkness – you could say that this is their natural state, beyond the brief moment they are brought out for public viewing. Or perhaps they are destroyed in order to create space for new things. Somebody told me that before Phyllida Barlow was PHYLLIDA BARLOW she threw her sculptures into The Thames under cover of night because they were too big and unwieldy to keep in her house. A singular, performative gesture that is steeped in drama, loneliness and subterfuge. And of course, sometimes sculptures are reinvented by their authors, taking on a new life in another guise; necessity creating the conditions for magical thinking.

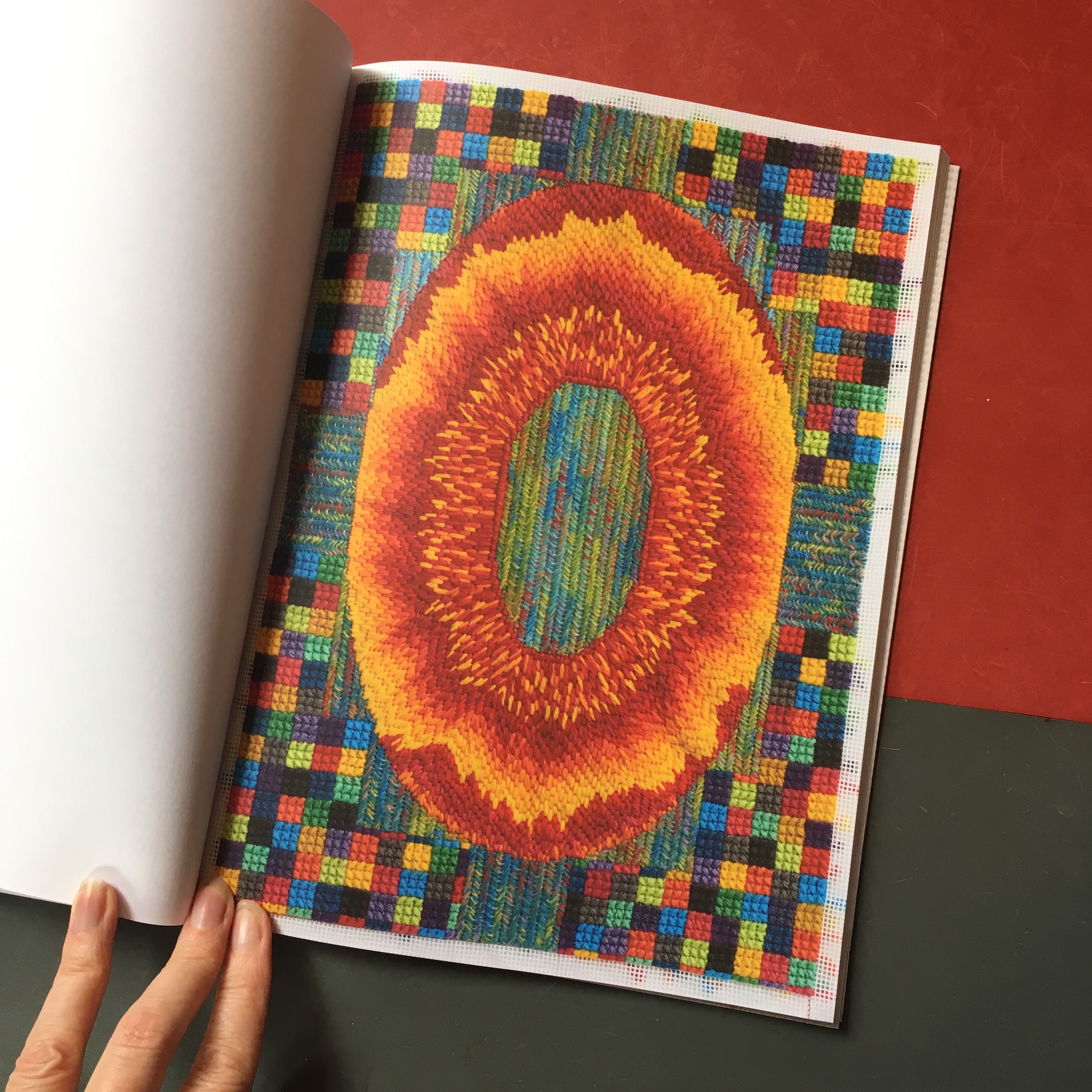

Sarah Ryder stores and remakes her sculptures in the most beguiling of ways. They are made from household foil - a light, flimsy material found in kitchen drawers the world over. But when she glues these sheets together they assume the form of heavy, weighty things - things that take up a lot of space and demand our attention. When the need arises, Ryder neatly folds these unruly, overflowing structures into perfectly formed, compressed squares and files them in cupboards, like album sleeves, in the basement of her house. At a later point, they become the raw material for new works and are given new titles, accreting stories and memory traces in the process.

Apart from being a pleasing solution to a practical problem, this file-and-retrieve approach articulates Ryder’s life-long commitment to challenging power structures and systems of control that dictate the way we live, act and make art. The counter-appropriation of everyday raw material give her sculptures a democratic feel, working against the machinery of commodification and control embedded within capitalist systems and more directly, the artworld. They refuse to retain a consistent form that can be bought, sold and consumed in any straightforward way; they are messy, they droop and degrade, they revel in their own anarchic materiality and seep into places they aren’t invited into (her studio is tiny - the work expands into other parts of the house); they are made with the full investment of her body, foil laid out on the floor or hung from the wall, with Ryder’s arms, hands, legs, feet applying paint to surface, grasping for space just beyond reach. They move ‘in an “off” register, embracing tangents, zigzags, sidesteps, doubling back and stumbling forward again’.

I’m hesitant to use the word ‘anarchic’ in relation to an artist or their practice – it has lost its power in recent years – but there is an urgent sense of refusal that aligns Ryder’s work with the writing of foundational feminist anarchists such as Emma Goldman (1869 - 1940). This radical thinker spoke of anarchy as a natural order, arising out of the community and solidarity of interests. Yes, she wanted to abolish the state, institute free love and get rid of prisons, but she conceived all this with a heady combination of rigorous, critical thinking and reckless abandon. She wanted to be truly free and, as a woman, she understood that her project differed from that of her male peers. She was famously reprimanded by a fellow anarchist for dancing at a public meeting: ‘it doesn’t behoove an agitator to dance’, he said; to which she absolutely did not reply ‘If I can’t dance, I don’t want to be part of your revolution’, even though this was the sentiment for which she is remembered a hundred years on. As a working class woman with meagre resources who constantly resists being contorted by the system, Ryder has found a home in Goldman’s anarcha-feminism, a movement that insists on the interconnectedness of different forms of oppression and seeks to create a society free from hierarchy and domination. But also, crucially, Goldman’s quite beautiful attempt to combine rigour with freedom and abandon is closely aligned to Ryder’s practice. While she steadfastly employs all her skill, focus, faculties and convictions to make her sculptures there are always moments when she lets go, removing herself from the equation to allow the artwork to become what it needs to be. It is a serious, joyful process that merges Ryder’s political convictions with the way she lives her life. This is life and art as activism; neither can be disentangled from the other.

This generosity extends to the way that audiences are invited to experience Ryder’s sculptures. There is no prescribed route or hint of a beginning and end, and there are no diktats concerning modes of acceptable behaviour in the gallery space. Ryder wants us to feel, respond to, walk around and revel in these works in any way that feels right or strange or interesting to us. These secreted, cave-like, feral structures create multiple viewpoints that we are invited to experience with our bodies, our minds, our eyes, our most basic, sophisticated selves.

The question so often posed by artists who align themselves with a political cause is: What can art do? How can the work I produce in my studio, as a solo-practitioner, make a difference? Ryder is clear that her aim is to construct a two-way relationship with her audiences in order to energise both them and her - to create a connection that produces a feeling of possibility in all parties. At the very least, to not feel so alone. Enter Emma Goldman once again, with her unorthodox view that the individual is a catalyst for the collective. Artists, thinkers and agitators, she said, are able to open up new pathways of imagination that could be adopted by a movement or embedded within a public psyche. It is the feeling of liberation and agency that Ryder aims to instil in those who experience her work. Come and join the party.

Photo: Sarah Ryder, Exeter Phoenix installation, 2025.

Sarah Ryder stores and remakes her sculptures in the most beguiling of ways. They are made from household foil - a light, flimsy material found in kitchen drawers the world over. But when she glues these sheets together they assume the form of heavy, weighty things - things that take up a lot of space and demand our attention. When the need arises, Ryder neatly folds these unruly, overflowing structures into perfectly formed, compressed squares and files them in cupboards, like album sleeves, in the basement of her house. At a later point, they become the raw material for new works and are given new titles, accreting stories and memory traces in the process.

Apart from being a pleasing solution to a practical problem, this file-and-retrieve approach articulates Ryder’s life-long commitment to challenging power structures and systems of control that dictate the way we live, act and make art. The counter-appropriation of everyday raw material give her sculptures a democratic feel, working against the machinery of commodification and control embedded within capitalist systems and more directly, the artworld. They refuse to retain a consistent form that can be bought, sold and consumed in any straightforward way; they are messy, they droop and degrade, they revel in their own anarchic materiality and seep into places they aren’t invited into (her studio is tiny - the work expands into other parts of the house); they are made with the full investment of her body, foil laid out on the floor or hung from the wall, with Ryder’s arms, hands, legs, feet applying paint to surface, grasping for space just beyond reach. They move ‘in an “off” register, embracing tangents, zigzags, sidesteps, doubling back and stumbling forward again’.

I’m hesitant to use the word ‘anarchic’ in relation to an artist or their practice – it has lost its power in recent years – but there is an urgent sense of refusal that aligns Ryder’s work with the writing of foundational feminist anarchists such as Emma Goldman (1869 - 1940). This radical thinker spoke of anarchy as a natural order, arising out of the community and solidarity of interests. Yes, she wanted to abolish the state, institute free love and get rid of prisons, but she conceived all this with a heady combination of rigorous, critical thinking and reckless abandon. She wanted to be truly free and, as a woman, she understood that her project differed from that of her male peers. She was famously reprimanded by a fellow anarchist for dancing at a public meeting: ‘it doesn’t behoove an agitator to dance’, he said; to which she absolutely did not reply ‘If I can’t dance, I don’t want to be part of your revolution’, even though this was the sentiment for which she is remembered a hundred years on. As a working class woman with meagre resources who constantly resists being contorted by the system, Ryder has found a home in Goldman’s anarcha-feminism, a movement that insists on the interconnectedness of different forms of oppression and seeks to create a society free from hierarchy and domination. But also, crucially, Goldman’s quite beautiful attempt to combine rigour with freedom and abandon is closely aligned to Ryder’s practice. While she steadfastly employs all her skill, focus, faculties and convictions to make her sculptures there are always moments when she lets go, removing herself from the equation to allow the artwork to become what it needs to be. It is a serious, joyful process that merges Ryder’s political convictions with the way she lives her life. This is life and art as activism; neither can be disentangled from the other.

This generosity extends to the way that audiences are invited to experience Ryder’s sculptures. There is no prescribed route or hint of a beginning and end, and there are no diktats concerning modes of acceptable behaviour in the gallery space. Ryder wants us to feel, respond to, walk around and revel in these works in any way that feels right or strange or interesting to us. These secreted, cave-like, feral structures create multiple viewpoints that we are invited to experience with our bodies, our minds, our eyes, our most basic, sophisticated selves.

The question so often posed by artists who align themselves with a political cause is: What can art do? How can the work I produce in my studio, as a solo-practitioner, make a difference? Ryder is clear that her aim is to construct a two-way relationship with her audiences in order to energise both them and her - to create a connection that produces a feeling of possibility in all parties. At the very least, to not feel so alone. Enter Emma Goldman once again, with her unorthodox view that the individual is a catalyst for the collective. Artists, thinkers and agitators, she said, are able to open up new pathways of imagination that could be adopted by a movement or embedded within a public psyche. It is the feeling of liberation and agency that Ryder aims to instil in those who experience her work. Come and join the party.

Photo: Sarah Ryder, Exeter Phoenix installation, 2025.

YOU ARE HERE

Essay for The Line, East London's public art trail. Published by Phaidon, 2025

Let’s start here, where you are standing, sitting, looking, hunching, breathing. This is the beginning. Throw yourself into a crisp winter’s day at the end of the first quarter of the twenty-first century. It’s late afternoon, the sun casts enormous greedy shadows over the landscape around you. We are in North Greenwich, an area in east London that conjures images of majestic excess, ships, architectural grandeur and a dictatorial relationship to the constructs of time. You can see your breath ahead of you as you begin to walk towards the river, that bit that forms a magnificent ‘U’ and is framed by the Isle of Dogs, where Henry VIII kept his canine friends. To the east of here lies the truncated runway of London City Airport, from where the world stretches out ad infinitum. A black-headed gull squawks overhead, gliding towards a place that doesn’t involve you; a cyclist rushes past, smiling at something you can’t see. There’s the hum of industry: construction sites, cranes in motion, ventilation shafts, 21st century white noise - all folded into a rich, fraught history of ship building and dock work. A man wearing a lanyard appears on the other side of a fence; he looks like he’s dreaming, not working. There are closed ecosystems here that are self-sufficient and mute; but there are others that invite you in, pointing towards past and future possibilities and things unknown, posing questions, proposing answers, issuing provocations.

Some of these generous, open systems take the form of artworks, installed by the river, over the river, on the river, on railings, walkways, and buildings, from North Greenwich to Stratford. Together, they suggest ways of relating to the world, to ourselves, and things we have built up around us. I want to say that they, and the environment in which they sit, inspire a kind of epiphany, but that sounds too grand for an experience that insists that you are not the main actor.

At the top of a pole, on this walkway at the tip of Greenwich Peninsula, there’s an unprepossessing municipal road sign that reads Here 24,859. It is an artwork by Alison Craighead and Jon Thomson that locates you in space and informs you, in a beautifully concise manner, that if you were to fly around the earth to arrive back at yourself, you will have travelled 24,859 miles. I’m thinking of my daughter as a baby, crawling up the stairs for the first time, glancing back at me, grinning with toothless pride. I realised that I’d been conceiving of her life as a set of future possibilities (What will she become? How will she relate to the world?) and understood that she is what she is now, here, in this moment, and this is what matters. And here I am, twenty-four years later, thinking of it again, reflecting on our need to construct narratives using time and distance as tools to build our worlds and tether us to life.

I walk on, my hands increasingly numb with cold, watching three men fix a puncture. They are in good spirits; their Lycra-clad bodies suggest that they aren’t in a hurry, there’s nothing important to get to. I come across a section of boat that has been bolted into the riverbed. Installed to celebrate the millennium twenty-five years ago, this is Richard Wilson’s sublime offering to the maritime gods, A Slice of Reality: an ocean sand dredger called the Arco Trent that he cut through to reveal the innards. I can see bits of ramshackle furniture, a faded album cover placed up against the window (is that the chiselled face of Feargal Sharkey surveying the water quality below?), and pipes that no longer provide a function beyond intrigue. This hulking great object that is so easy to miss unless you are told to see it, alludes to the violence of the Meridian line. Forged 140 years ago to prop up a universal understanding of time, it helps us cut across the specificities of cultures and lives with effortless indifference and criminal insensitivity. This artwork tethers us to a history of Empire that is both painful and significant. It is ageing alongside us and gets more ragged and complex every year. A friend messages to tell me that she called the mobile number posted on a hand-painted wooden plaque on the boat. The artist picked up. They had a great chat, she said. This is a special kind of public offering. The art, the artist, the history, the light, the thing.

The river is a constant companion for much of this walk. It is murky and dense, light glancing off its silvery surface. It is famously hard to photograph, and, like anything worth its salt, it has a strong undercurrent. It holds a multitude of secrets. I read somewhere that before Phyllida Barlow was PHYLLIDA BARLOW she would – under cover of darkness - throw her sculptures into the Thames because she couldn’t afford to store them. So there’s art down there, as well as bits of old pottery, bottle tops, coins, shopping trollies, bones and bodies. On average (it says here, in my phantasmic AI-facilitated online search), a human body is found in the Thames once a fortnight. That’s a lot of violence, misery, secrets and shadows. This collection of human effluence is accompanied by rats and seals, eels and seahorses, leafy-dragons and sharks. A myriad of fantastical creatures inhabit this underworld. From the corner of my mind’s eye, I see the ghosts of pirates who were hanged at Wapping, whose bodies were grimly displayed along the Peninsula as a deterrent to those considering similar acts of extraction by stealth.

Not far up from Wilson’s dredger, I find Tribe and Tribulation, Serge Attukwei Clottey’s totemic sculpture and am transported from my dark piratical reverie to Accra, in Ghana, the only other capital city that sits on the prime meridian. Made from fragments of Ghanaian fishing boats, this majestic, towering structure emits the sound of activity in the former slave forts of Cape Coast Castle, Elmina Castle and James Fort: fishermen and women hustling, waves crashing, birds screeching, things clanking. These abandoned forts have been reclaimed through trade, migration, industrialisation and a complex web of consumerism and inequality. If I squint into the light, I can see a procession of children weaving their way through the streets of Greenwich and Accra, wearing masks they have fashioned from discarded material, plastic bottles, cardboard, paint and fabric. They are dancing, chanting and banging drums, assuming fantastical characters in wild abandon. It feels like a tear in the time-space continuum has opened up and the children are inhabiting both cities at the same moment. Riverboats toot their horns, there is freedom and glee in the air; a sense of future possibilities and connectedness traversing the globe. Everyone, it seems, is smiling.

This walking route lies on the margins of London. It is rough edgeland that speaks of lived reality, lives lived in compromised, beautiful, bewildering complexity. It is haphazard, ragged, bolted together by the necessities of survival rather than some finely authored singular flourish. The neoliberalizing property cadre have only partly moved in, dipping their toes in the river to gauge the temperature of their likely net profits. This frayed world is echoed in the wild, abstract drawings of self-taught, local artist Madge Gill (1882 – 1961), whose artwork is installed across five locations on The Line. At Cody Dock, the sun glances off a bridge that has been clad in a detail of one of her fantastical drawings, and in the walkway leading up to the dock there’s a tender photograph of her wearing one of her multi-coloured, sculptural dresses. She is leaning against a baroque 19th century cabinet that reeks of showy ‘exoticism’ and cares nothing for this frail, self-conscious old woman, with her parted grey hair, gnarled hands and downward glance. But how majestic and other-worldly she looks, wearing this dress that refuses the mores of contemporary life and embraces an inner world of imagination and play.

Gill’s life was hard; she lived for a while in an orphanage as a child, survived on meagre resources, suffered from mental turmoil as a result of the death of two children, and received little public recognition for her work. She had a spirit guide called Myrninerest and used paint, inks and textiles to create thousands of drawings in which spiderwebs, faces, petals, buildings and chequerboards dance together in a kind of fraught ecstasy. In another photograph, sited further along the wall, there she is unravelling one of her huge eight-metre calico drawings in her garden. Her floral shapes form a union with the light and plants of the natural world; it’s an alchemic, strangely hopeful vision, made all the more poignant by the quality of the photograph’s fading and the surrounding plant life of the dock. Madge Gill: remember her name. She’s receiving her due now, more than half a century after her death, her ghost haunting an art historical canon that seems to take pride in its exclusion of people living on the edges.

When I walk over Simon Faithfull’s thirty-eight paving stones that reference the 0° line of longitude, I think back to Wilson’s boat and reflect on the absurdity and hubris of this carving of the globe into a series of parallel lines, how it created the necessary culture of time for building empires, and how that culture is still with us, embedded in our language, our institutions, the way we view the world, and the continued impoverishment and underdevelopment of supposedly ‘post’-colonized states. Writer Giordano Nanni reminds us that ‘clocks…do not keep the time, but a time’ and Edward Said wrote about the West’s West v. East, how these are ‘ideological fictions,…constructs...weapons of cultural war’, but he could just as easily be talking about time. It took me far too long to realise that the East is only the East if you are standing in the West. As a child, my parents had a Turkish world atlas that they kept on a shelf in the living room. The cloth cover was a dreamy mediterranean sea blue, and of course all the text, including country and city names, was Turkish. I realised, as an adult, I had navigated the early part of my life harbouring a hazy sense that the world was Turkish and that all other languages and countries were somehow a permitted concession to its otherwise hegemonic dominance. The irony! Me with my British passport and all its accompanying privileges.

Along the walkway that takes me from Three Mills to Sugar House Island, I meet a man with a wildly enthusiastic little dog whose wagging tail seems to dictate the terms of his engagement. The man tells me that a car accident rendered him unable to work. He walks this segment of The Line every day; it has helped him piece things back together, he says. The artworks, the landscape, the sounds, the birds, the neighbours - they have all supported him along the way. I feel quite emotional thinking about the implications of all this, how important it is for us to be able to find places, things, people that are there for us when things fall apart, and how hard this is in a world that is increasingly fragmented, monetised, mined, hollowed out. The dog refuses my mawkishness and is busy greeting everyone who walks by with a proprietorial air. His owner smiles proudly and says: ‘He thinks this is his garden and these people are just visitors’.

Recently, I have become interested in ways that we can mark time in relation to public artworks. These things that are in our lives over long periods, they can become

barometers for gauging the rate of change all around, the ageing process, the shifting of a mindset or life-choices. We experience them with our bodies, our breath, our current reality, our daydreams, our perfectly strange, muffled attempts to map out our day and locate ourselves in the world. When I first saw Wilson’s boat in the enthusiastic fan-fare that was the millennium, I was thirty-one. 9/11 and the Iraq War had not yet happened and we were marching blithely past threats of a future climate catastrophe. I was old enough to recognise what I was becoming, but young enough to potentially misconstrue the narrative. Looking at A Slice of Reality now, I am able to somehow conjure an invisible, rich, knotted thread, that is both incredibly personal and fantastically universal, which stretches from the past to arrive at the present, nodding to a notional, unseeable future.

When we make friends with an artwork, it can be alarming when it disappears. There are many reasons why this might happen: damage, decay, destruction, a new home elsewhere, a finite lifespan. When Tracey Emin’s tiny bronze birds were deinstalled from their location on the bank of Three Mills River, local people expressed their sorrow. Perched on top of slender poles, with a dramatic backdrop that encompassed the world’s largest surviving tidal mill, these fragile little convinced characters seemed to look out for us all, chattering to each other across the airwaves. During Covid, a local woman took solace in the sculpture, reflecting on the recent deaths of family members. I imagine that she was sad to see the birds go. This mourning of an absent artwork is a powerful reminder of our own mortality as well as the importance of valuing something in the moment, but most beguilingly, it can teach us that a void can be more insistent and ‘real’ than something in its embodied state. I’m hoping that the site that once held A Moment Without You becomes an ongoing space for expansive reflection. I often think about the fact that thousands of people queued for hours to see the space left by the stolen Mona Lisa at the Louvre in 1911. There’s a blurry black and white photograph of packed crowds fiercely studying a dusty wall. The emptiness that marks the absence of an artwork can take root in our imagination and assume a chameleon-like narrative that bends to suit the occasion, the storyteller, or the revised context. It poses the idea that perhaps we can see something more clearly when it’s not there.

We have reached Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park at Stratford, the end of The Line, which is the beginning for many. It is dark; we emerge into the noise, the lights, the people, the movement of city life. The fledgling waterfront development at East Bank, constructed on the foundations of London’s 2012 sporting endeavour, as well as centuries of toil by brewers, potato farmers and weavers, is setting down roots, testing its relation to the rest of the city. I’m not entirely ready for this reintroduction, but I’m taking this gift, this folding and unravelling of time and the dreaming of artists, to shore up my reserves, to make future things possible.

Some of these generous, open systems take the form of artworks, installed by the river, over the river, on the river, on railings, walkways, and buildings, from North Greenwich to Stratford. Together, they suggest ways of relating to the world, to ourselves, and things we have built up around us. I want to say that they, and the environment in which they sit, inspire a kind of epiphany, but that sounds too grand for an experience that insists that you are not the main actor.

At the top of a pole, on this walkway at the tip of Greenwich Peninsula, there’s an unprepossessing municipal road sign that reads Here 24,859. It is an artwork by Alison Craighead and Jon Thomson that locates you in space and informs you, in a beautifully concise manner, that if you were to fly around the earth to arrive back at yourself, you will have travelled 24,859 miles. I’m thinking of my daughter as a baby, crawling up the stairs for the first time, glancing back at me, grinning with toothless pride. I realised that I’d been conceiving of her life as a set of future possibilities (What will she become? How will she relate to the world?) and understood that she is what she is now, here, in this moment, and this is what matters. And here I am, twenty-four years later, thinking of it again, reflecting on our need to construct narratives using time and distance as tools to build our worlds and tether us to life.

I walk on, my hands increasingly numb with cold, watching three men fix a puncture. They are in good spirits; their Lycra-clad bodies suggest that they aren’t in a hurry, there’s nothing important to get to. I come across a section of boat that has been bolted into the riverbed. Installed to celebrate the millennium twenty-five years ago, this is Richard Wilson’s sublime offering to the maritime gods, A Slice of Reality: an ocean sand dredger called the Arco Trent that he cut through to reveal the innards. I can see bits of ramshackle furniture, a faded album cover placed up against the window (is that the chiselled face of Feargal Sharkey surveying the water quality below?), and pipes that no longer provide a function beyond intrigue. This hulking great object that is so easy to miss unless you are told to see it, alludes to the violence of the Meridian line. Forged 140 years ago to prop up a universal understanding of time, it helps us cut across the specificities of cultures and lives with effortless indifference and criminal insensitivity. This artwork tethers us to a history of Empire that is both painful and significant. It is ageing alongside us and gets more ragged and complex every year. A friend messages to tell me that she called the mobile number posted on a hand-painted wooden plaque on the boat. The artist picked up. They had a great chat, she said. This is a special kind of public offering. The art, the artist, the history, the light, the thing.

The river is a constant companion for much of this walk. It is murky and dense, light glancing off its silvery surface. It is famously hard to photograph, and, like anything worth its salt, it has a strong undercurrent. It holds a multitude of secrets. I read somewhere that before Phyllida Barlow was PHYLLIDA BARLOW she would – under cover of darkness - throw her sculptures into the Thames because she couldn’t afford to store them. So there’s art down there, as well as bits of old pottery, bottle tops, coins, shopping trollies, bones and bodies. On average (it says here, in my phantasmic AI-facilitated online search), a human body is found in the Thames once a fortnight. That’s a lot of violence, misery, secrets and shadows. This collection of human effluence is accompanied by rats and seals, eels and seahorses, leafy-dragons and sharks. A myriad of fantastical creatures inhabit this underworld. From the corner of my mind’s eye, I see the ghosts of pirates who were hanged at Wapping, whose bodies were grimly displayed along the Peninsula as a deterrent to those considering similar acts of extraction by stealth.

Not far up from Wilson’s dredger, I find Tribe and Tribulation, Serge Attukwei Clottey’s totemic sculpture and am transported from my dark piratical reverie to Accra, in Ghana, the only other capital city that sits on the prime meridian. Made from fragments of Ghanaian fishing boats, this majestic, towering structure emits the sound of activity in the former slave forts of Cape Coast Castle, Elmina Castle and James Fort: fishermen and women hustling, waves crashing, birds screeching, things clanking. These abandoned forts have been reclaimed through trade, migration, industrialisation and a complex web of consumerism and inequality. If I squint into the light, I can see a procession of children weaving their way through the streets of Greenwich and Accra, wearing masks they have fashioned from discarded material, plastic bottles, cardboard, paint and fabric. They are dancing, chanting and banging drums, assuming fantastical characters in wild abandon. It feels like a tear in the time-space continuum has opened up and the children are inhabiting both cities at the same moment. Riverboats toot their horns, there is freedom and glee in the air; a sense of future possibilities and connectedness traversing the globe. Everyone, it seems, is smiling.

This walking route lies on the margins of London. It is rough edgeland that speaks of lived reality, lives lived in compromised, beautiful, bewildering complexity. It is haphazard, ragged, bolted together by the necessities of survival rather than some finely authored singular flourish. The neoliberalizing property cadre have only partly moved in, dipping their toes in the river to gauge the temperature of their likely net profits. This frayed world is echoed in the wild, abstract drawings of self-taught, local artist Madge Gill (1882 – 1961), whose artwork is installed across five locations on The Line. At Cody Dock, the sun glances off a bridge that has been clad in a detail of one of her fantastical drawings, and in the walkway leading up to the dock there’s a tender photograph of her wearing one of her multi-coloured, sculptural dresses. She is leaning against a baroque 19th century cabinet that reeks of showy ‘exoticism’ and cares nothing for this frail, self-conscious old woman, with her parted grey hair, gnarled hands and downward glance. But how majestic and other-worldly she looks, wearing this dress that refuses the mores of contemporary life and embraces an inner world of imagination and play.

Gill’s life was hard; she lived for a while in an orphanage as a child, survived on meagre resources, suffered from mental turmoil as a result of the death of two children, and received little public recognition for her work. She had a spirit guide called Myrninerest and used paint, inks and textiles to create thousands of drawings in which spiderwebs, faces, petals, buildings and chequerboards dance together in a kind of fraught ecstasy. In another photograph, sited further along the wall, there she is unravelling one of her huge eight-metre calico drawings in her garden. Her floral shapes form a union with the light and plants of the natural world; it’s an alchemic, strangely hopeful vision, made all the more poignant by the quality of the photograph’s fading and the surrounding plant life of the dock. Madge Gill: remember her name. She’s receiving her due now, more than half a century after her death, her ghost haunting an art historical canon that seems to take pride in its exclusion of people living on the edges.

When I walk over Simon Faithfull’s thirty-eight paving stones that reference the 0° line of longitude, I think back to Wilson’s boat and reflect on the absurdity and hubris of this carving of the globe into a series of parallel lines, how it created the necessary culture of time for building empires, and how that culture is still with us, embedded in our language, our institutions, the way we view the world, and the continued impoverishment and underdevelopment of supposedly ‘post’-colonized states. Writer Giordano Nanni reminds us that ‘clocks…do not keep the time, but a time’ and Edward Said wrote about the West’s West v. East, how these are ‘ideological fictions,…constructs...weapons of cultural war’, but he could just as easily be talking about time. It took me far too long to realise that the East is only the East if you are standing in the West. As a child, my parents had a Turkish world atlas that they kept on a shelf in the living room. The cloth cover was a dreamy mediterranean sea blue, and of course all the text, including country and city names, was Turkish. I realised, as an adult, I had navigated the early part of my life harbouring a hazy sense that the world was Turkish and that all other languages and countries were somehow a permitted concession to its otherwise hegemonic dominance. The irony! Me with my British passport and all its accompanying privileges.

Along the walkway that takes me from Three Mills to Sugar House Island, I meet a man with a wildly enthusiastic little dog whose wagging tail seems to dictate the terms of his engagement. The man tells me that a car accident rendered him unable to work. He walks this segment of The Line every day; it has helped him piece things back together, he says. The artworks, the landscape, the sounds, the birds, the neighbours - they have all supported him along the way. I feel quite emotional thinking about the implications of all this, how important it is for us to be able to find places, things, people that are there for us when things fall apart, and how hard this is in a world that is increasingly fragmented, monetised, mined, hollowed out. The dog refuses my mawkishness and is busy greeting everyone who walks by with a proprietorial air. His owner smiles proudly and says: ‘He thinks this is his garden and these people are just visitors’.

Recently, I have become interested in ways that we can mark time in relation to public artworks. These things that are in our lives over long periods, they can become

barometers for gauging the rate of change all around, the ageing process, the shifting of a mindset or life-choices. We experience them with our bodies, our breath, our current reality, our daydreams, our perfectly strange, muffled attempts to map out our day and locate ourselves in the world. When I first saw Wilson’s boat in the enthusiastic fan-fare that was the millennium, I was thirty-one. 9/11 and the Iraq War had not yet happened and we were marching blithely past threats of a future climate catastrophe. I was old enough to recognise what I was becoming, but young enough to potentially misconstrue the narrative. Looking at A Slice of Reality now, I am able to somehow conjure an invisible, rich, knotted thread, that is both incredibly personal and fantastically universal, which stretches from the past to arrive at the present, nodding to a notional, unseeable future.

When we make friends with an artwork, it can be alarming when it disappears. There are many reasons why this might happen: damage, decay, destruction, a new home elsewhere, a finite lifespan. When Tracey Emin’s tiny bronze birds were deinstalled from their location on the bank of Three Mills River, local people expressed their sorrow. Perched on top of slender poles, with a dramatic backdrop that encompassed the world’s largest surviving tidal mill, these fragile little convinced characters seemed to look out for us all, chattering to each other across the airwaves. During Covid, a local woman took solace in the sculpture, reflecting on the recent deaths of family members. I imagine that she was sad to see the birds go. This mourning of an absent artwork is a powerful reminder of our own mortality as well as the importance of valuing something in the moment, but most beguilingly, it can teach us that a void can be more insistent and ‘real’ than something in its embodied state. I’m hoping that the site that once held A Moment Without You becomes an ongoing space for expansive reflection. I often think about the fact that thousands of people queued for hours to see the space left by the stolen Mona Lisa at the Louvre in 1911. There’s a blurry black and white photograph of packed crowds fiercely studying a dusty wall. The emptiness that marks the absence of an artwork can take root in our imagination and assume a chameleon-like narrative that bends to suit the occasion, the storyteller, or the revised context. It poses the idea that perhaps we can see something more clearly when it’s not there.

We have reached Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park at Stratford, the end of The Line, which is the beginning for many. It is dark; we emerge into the noise, the lights, the people, the movement of city life. The fledgling waterfront development at East Bank, constructed on the foundations of London’s 2012 sporting endeavour, as well as centuries of toil by brewers, potato farmers and weavers, is setting down roots, testing its relation to the rest of the city. I’m not entirely ready for this reintroduction, but I’m taking this gift, this folding and unravelling of time and the dreaming of artists, to shore up my reserves, to make future things possible.

FROM BREATH TO DUST

Text for Od Festival, 2025

Listen to audio recording here

To reach the underworld, I walk on grass, tarmac, roots, concrete and soil. It’s not a long journey, but it’s more than likely that I kill a number of insects, fungi, and other microcosms along the way. I sit in a field and place headphones on my ears. I look up at the sky. I am on the surface of the Earth, hurtling through space at 1,000 mph but all is still, just faintly twitching. My torso is rising and falling, air is inhaled and exhaled into and out of my body, the beating of my heart dictates the terms of my existence. In my pockets there is a train ticket (I have come from somewhere!), tissues, an OD Festival badge, my phone. I am a body in the overworld listening to the sounds of the underworld through a series of wires and alchemical processes. It is an experiment in the transformation of one form of energy into another and I am stunned by what I hear.

There is a continuous electronic hum; a boat clanking against a dock; doors banging, shutting, creaking; things croaking, clicking, reverberating, drilling, knocking; heavy boxes being dragged across a floor; things under water, drowning, living, screaming. For something that looks so solid and can hold such weight, the underworld is fantastically mutable, noisy and teeming with life. Occasionally, bits of the upperworld seep into the soundscape: atmospheric chatter produced by plants, dogs, birds and people. This bleeding no doubt continues to unfold between the overworld and the heavens. There is always bleeding. Everything is porous.

In the world of myth and religious story-telling, the underworld assumes an altogether more malevolent character. There are fights and factions, spirits dying and dead, tantrums and dissonance. This hellish landscape is dark, unknown and unseeable. It is inhabited by chthonic deities and associated with a heady mix of death and fertility. There’s Hades, God of the Underworld, moaning about how expensive it is to keep a three-headed dog. His wealth doesn’t stem his sense of resentment that his brothers got the better deal – Zeus, the sky, and Poseidon, the sea. More horizon and access to clarity in both these worlds, he thinks. The lack of sunlight in the underworld means that Hades suffers from bone pain and muscle weakness; his skin is horribly sensitive and comes off in huge flakes. On the upside, he’ll probably outlive his siblings.

In the inner workings of our minds, the underworld presents as an existential void, carrying abjection and raw being. Characters in books and films enter the underworld by falling into madness, crossing a threshold, tipping into an inner decent where bad things happen. It is a place of transformation, inversion, initiation. A journey into the depths of the self.

A muffled voice - coming from somewhere far away – enters my consciousness. It becomes more insistent and I blink my eyes open. I re-enter the overworld reluctantly. I felt soothed by those murky depths, like my body was in a fluid, blind state, and now I must negotiate gravity, people, the sun.

In the overworld I discover that other things are happening. A man whose friend is lost describes a journey through 1990s post-industrial England. There is moral scowling, shopping centres, Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, container ships and a search for utopia. I am attracted by the monotone voice, the quite boring details, the expanse of strangeness that human life manufactures. A Museum of Roadside Magic teaches us how to create our own universe if the one we inhabit doesn’t work for us. A woman does a reading in a small converted school room about violence, destruction, plants, her mother, her native Colombia. It feels like we are at the centre of the world, learning everything and nothing. Multiple, layered human voices reverberate through the vaults of an eight-hundred-year-old church. People sit hunched in pews, shrouded in sound which turns into a kind of textured, all-enveloping material. A blue atomic haystack inhabits a fifteenth century manor house, seductive, contaminated, dark. It smells of wild meadow and is restless, its toxic state pointing to the many inventive ways that we are destroying our planet. Nearby, a snake eats its tale while birds and trees inhabit the celestial heavens above.

The backdrop to these infinitesimal worlds exists in the form of thatched cottages made of Hamstone, a locally quarried, warm, honey-coloured Jurassic rock. Mullioned windows are dressed in wisteria, climbing roses and ivy. Buildings that seem to emanate from the land are linked by ancient lanes called holloways, formed over centuries by erosion and the movement of bodies across pliant earth. These holloways, they are a kind of flattened underworld worn smooth by horses, mythical beings and daily footfall. A butterfly settles on a nearby plant. The sun slides in to view. There is very little impression that all is far from well in the overworld beyond.

T S Eliot’s ashes are buried in a nearby churchyard. His body reduced to a mound of grey flakes that have now gone back to the earth. “In my beginning is my end” Eliot says in his poem ‘East Coker’. We must all go back to the earth – as bodies or ashes, but always, ultimately, dust.

I find a broken-looking trowel in the churchyard and wonder what would happen if I dug downwards from here. Would I encounter the underworld and eventually meet the other side of the earth? It is hard work at first (the trowel is almost useless), but then I am lost in a rhythmic motion and strange things begin to happen. I don’t see Hades - his helmet of invisibility saves him from this indignity - but I glimpse an array of amorphous bodies that look not exactly dead but certainly not alive. I exchange oxygen for methane and experience searing pain, heat, darkness. After what seems like either a millennium or a few seconds, I come up, gasping for air, in the southern Pacific Ocean. It is really cold, my jaw is frozen, slightly open, as I flail towards land, somewhere southeast of New Zealand.

I hitch a lift with a lost, mute soul (perhaps his name was Robinson) and arrive back at where I started. It’s a long journey and I take the opportunity to think about the soundscape of the underworld, as well as the ways that things rise and fall and are reborn (until they’re not). I understand with a kind of earthy, alarming clarity that everything is interconnected and that we are always at the beginning and end of things, from breath to dust.

Photo: Michelle Attherton's Soil Seance, 2023. Credit: Sylvia Fanstenhammer.

To reach the underworld, I walk on grass, tarmac, roots, concrete and soil. It’s not a long journey, but it’s more than likely that I kill a number of insects, fungi, and other microcosms along the way. I sit in a field and place headphones on my ears. I look up at the sky. I am on the surface of the Earth, hurtling through space at 1,000 mph but all is still, just faintly twitching. My torso is rising and falling, air is inhaled and exhaled into and out of my body, the beating of my heart dictates the terms of my existence. In my pockets there is a train ticket (I have come from somewhere!), tissues, an OD Festival badge, my phone. I am a body in the overworld listening to the sounds of the underworld through a series of wires and alchemical processes. It is an experiment in the transformation of one form of energy into another and I am stunned by what I hear.

There is a continuous electronic hum; a boat clanking against a dock; doors banging, shutting, creaking; things croaking, clicking, reverberating, drilling, knocking; heavy boxes being dragged across a floor; things under water, drowning, living, screaming. For something that looks so solid and can hold such weight, the underworld is fantastically mutable, noisy and teeming with life. Occasionally, bits of the upperworld seep into the soundscape: atmospheric chatter produced by plants, dogs, birds and people. This bleeding no doubt continues to unfold between the overworld and the heavens. There is always bleeding. Everything is porous.

In the world of myth and religious story-telling, the underworld assumes an altogether more malevolent character. There are fights and factions, spirits dying and dead, tantrums and dissonance. This hellish landscape is dark, unknown and unseeable. It is inhabited by chthonic deities and associated with a heady mix of death and fertility. There’s Hades, God of the Underworld, moaning about how expensive it is to keep a three-headed dog. His wealth doesn’t stem his sense of resentment that his brothers got the better deal – Zeus, the sky, and Poseidon, the sea. More horizon and access to clarity in both these worlds, he thinks. The lack of sunlight in the underworld means that Hades suffers from bone pain and muscle weakness; his skin is horribly sensitive and comes off in huge flakes. On the upside, he’ll probably outlive his siblings.

In the inner workings of our minds, the underworld presents as an existential void, carrying abjection and raw being. Characters in books and films enter the underworld by falling into madness, crossing a threshold, tipping into an inner decent where bad things happen. It is a place of transformation, inversion, initiation. A journey into the depths of the self.

A muffled voice - coming from somewhere far away – enters my consciousness. It becomes more insistent and I blink my eyes open. I re-enter the overworld reluctantly. I felt soothed by those murky depths, like my body was in a fluid, blind state, and now I must negotiate gravity, people, the sun.

In the overworld I discover that other things are happening. A man whose friend is lost describes a journey through 1990s post-industrial England. There is moral scowling, shopping centres, Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, container ships and a search for utopia. I am attracted by the monotone voice, the quite boring details, the expanse of strangeness that human life manufactures. A Museum of Roadside Magic teaches us how to create our own universe if the one we inhabit doesn’t work for us. A woman does a reading in a small converted school room about violence, destruction, plants, her mother, her native Colombia. It feels like we are at the centre of the world, learning everything and nothing. Multiple, layered human voices reverberate through the vaults of an eight-hundred-year-old church. People sit hunched in pews, shrouded in sound which turns into a kind of textured, all-enveloping material. A blue atomic haystack inhabits a fifteenth century manor house, seductive, contaminated, dark. It smells of wild meadow and is restless, its toxic state pointing to the many inventive ways that we are destroying our planet. Nearby, a snake eats its tale while birds and trees inhabit the celestial heavens above.

The backdrop to these infinitesimal worlds exists in the form of thatched cottages made of Hamstone, a locally quarried, warm, honey-coloured Jurassic rock. Mullioned windows are dressed in wisteria, climbing roses and ivy. Buildings that seem to emanate from the land are linked by ancient lanes called holloways, formed over centuries by erosion and the movement of bodies across pliant earth. These holloways, they are a kind of flattened underworld worn smooth by horses, mythical beings and daily footfall. A butterfly settles on a nearby plant. The sun slides in to view. There is very little impression that all is far from well in the overworld beyond.

T S Eliot’s ashes are buried in a nearby churchyard. His body reduced to a mound of grey flakes that have now gone back to the earth. “In my beginning is my end” Eliot says in his poem ‘East Coker’. We must all go back to the earth – as bodies or ashes, but always, ultimately, dust.

I find a broken-looking trowel in the churchyard and wonder what would happen if I dug downwards from here. Would I encounter the underworld and eventually meet the other side of the earth? It is hard work at first (the trowel is almost useless), but then I am lost in a rhythmic motion and strange things begin to happen. I don’t see Hades - his helmet of invisibility saves him from this indignity - but I glimpse an array of amorphous bodies that look not exactly dead but certainly not alive. I exchange oxygen for methane and experience searing pain, heat, darkness. After what seems like either a millennium or a few seconds, I come up, gasping for air, in the southern Pacific Ocean. It is really cold, my jaw is frozen, slightly open, as I flail towards land, somewhere southeast of New Zealand.

I hitch a lift with a lost, mute soul (perhaps his name was Robinson) and arrive back at where I started. It’s a long journey and I take the opportunity to think about the soundscape of the underworld, as well as the ways that things rise and fall and are reborn (until they’re not). I understand with a kind of earthy, alarming clarity that everything is interconnected and that we are always at the beginning and end of things, from breath to dust.

Photo: Michelle Attherton's Soil Seance, 2023. Credit: Sylvia Fanstenhammer.

Ghosts and Sculpture

Catalogue text for 'Phantom Sculpture' exhibition at Mead Gallery, 2023 - 24. Published by University of Warwick, 2024

We are all haunted by the ghosts of our past, by the hoped-for things that never transpired, by the future that never arrived, by things we said that should have remained unsaid; things we didn’t say; friends, family, dreams and moments we have lost. If we are lucky, we are also visited by more generous, generative ghosts who ply us with enthusiasm and establish a hot-line to the past, creating possibilities for invention and hopeful futures. These ghosts, they shift around us as we move through the world. Sometimes we bump up against them and are startled by their insistence, their clarity, but mostly they are silent, acquiescent, living out their own lives in relative obscurity.

They teach us things, these ghosts. Perhaps it’s the same for artists as they navigate the histories of their discipline, sifting through the achievements, projects and failures of those who lived before them, accruing a pile of immaterial bodies and practices that move them, influence them, irritate them, shunt into their work in some way.

For Phantom Sculpture, works of art made over the past sixty years are presented alongside each other - the march of linear time, art historical movements, and accreted, developmental maps are compressed, tantalisingly live, as notes are passed from one generation to the next, whispers gathering across the gallery space. The artists all forge a connection to the British Isles, in that they were either born here, have spent time here, fled from here, or have lived their entire lives here. So, this is a story about the recent history of British sculpture, in all its parochial glory, bombast, dreaming and fragility.

The story contains many other stories, of course, but the dominance of the dominant story is notable for its insistence. The points at which the baton is handed over, dropped, smashed or cherished by artists of different generations, are clearly identifiable as we move, like an Art History undergraduate syllabus, through the decades. From 1950s abstraction, commitment to natural materials and a kind of post-war delirium (Hepworth), to the 1960s when the ‘New Generation’ banished the plinth in order to forge a more democratic relation to the viewer, and employed industrial and synthetic materials to make minimal, conceptual sculptures that resisted monumentality and embraced dematerialisation (Caro). By the 1980s, ‘New British Sculpture’ (always the new) fulfilled the role of recalcitrant child by rejecting their forebearers to produce elemental, sensual or metaphoric imagery, sometimes using traditional processes and materials (Turnbull). Working under the shadow of the Thatcher years, when the burgeoning free-market economy was establishing the tentacled, malign roots of neo-liberalism, these artists often used the debris of contemporary life to play with colour, humour, and variegated forms of physicality.

The 2000’s brought a less easily packaged range of approaches (the nearer we get to the present, the harder it is to identify the characteristics of an era – it takes time to paint out other voices). There’s the introduction of surrealist language, an exploration of the uncanny (Hatoum and Ekks), and an ongoing experimentation with materials and abstraction (Deacon). Bawdy, rule-breaking louchness was celebrated, and the ready-made was employed to celebrate irreverence and humour (Lucas). It was the dawn of a new millennium, we were drunk on the promise of a Labour government and the delusional idea that capitalist growth would deliver a slipstream of comfort for each successive generation. The Iraq War was the beginning of the end of the dream and by the 2010s we were reaching what Mark Fisher (via Franco Berardi) called ‘the slow cancellation of the future’ in which our ability to differentiate the past from the present was compromised by the impact of postmodernity. This ‘temporal bleed’ or ‘dyschromia’ created a strange simultaneity which, Fisher contends, made it hard to locate oneself in a creative present (there is no ‘now’).

And the 2020s? Where have we arrived? Well, every era seems to revel in the construction of its own cataclysmic end-time scenarios, but this decade is promising to deliver a quite spectacular range of possibilities including onanistic globalisation, muscular authoritarianism, aggressive exploitation of labour across and within countries, increasingly desperate refugee flows, social media-propelled right-wing nationalisms, the ongoing delusion of white supremacy, and the obscene, forever expanding chasm dividing the rich from the poor. As I write, the impact of Britain’s rapacious colonial past is rising to meet the present in the horrors that are unfolding in Palestine, Afghanistan, and the Sudan. And, the most cataclysmic cataclysm of them all, the unravelling climate catastrophe. It seems that Fisher underestimated the future of stunted or unrealised futures.

Throughout all of this, art is still made, things need to be said. The artists in Phantom Sculpture deliver a compelling array of disturbing, beautiful, poetic, angry responses to their place in the world. There is a glorious opening up of the range of voices that we are able to hear, reaching beyond the white, predominantly male makeup of recent art historical movements, to welcome the female, the Black, the disabled, the trans, the working class, the Other. Signalling a resounding refusal of old categories and assumptions around what can and can’t be said, there is a synthesis of figuration and abstraction, and a curiosity about the breakdown of binaries between the non-human and human, male and female, machine and organism.

The bombast of previous generations has gone. It has been replaced by fragility, ambiguity and tenderness (Freije, Ackroyd, Buckley, White, and Darling) along with an understanding of impermanence and our entanglement with nature and each other (Lai). There are shape-shifters and mystics in the fray (Baldock and Ekks), as well as unruly bodies that revel in sex and seduction (Ackroyd). Craft, the touch of the hand, the insistence of the power of making, is beautifully evident (Bax, Collings-James, Baldock, and Ryan), as is a scratching at the perversions of consumerism (Wermers). A refusal of Euro-centric modes of knowledge-building and history-making, and a move to create counter-histories, speculative models and forms of resistance are defiantly present (Collings-James, Buckley, Wahid, and White). And there’s an interest in words, language, different ways of making stories through experimental text and collaboration with writers (Bax, Darling, Buckley, Freije). All these approaches and projects, I think, make it easier for artists – and the artworks themselves – to socialise with, and learn from, ghosts. There is an openness, a vulnerability, a seepage into other worlds that conveys a tangible sense that there are many answers to the same question, and that multiple constellations are possible.

But this tidy, art historical narrative, that moves from the 1960s to the present day, obeys the diktats of linear time, and therefore appears to refuse temporal transgressions of ghostly travel across clearly delimited periods - and causal sequences. Maverick art historian Aby Warburg proposed, through his concept of Nachleben, that this disorienting mash-up of eras where images, in their anachronistic, enigmatic, metaphorical state, produce an afterlife that spans and moves through centuries and multiple art historical timeframes, leads to the ‘paradox where the oldest things may appear as less old ones’. Ghosts need to be able to move through time, to party with older, maybe no wiser ghosts, or ones who are new to the scene, just learning the ropes. It seems clear that dreams, lives, and artistic endeavours are not linear, they are fragmented, they fly across situations, centuries and generations. There is a crackle or glitch where time is out of joint, sounds gather and never die, and a cacophonous present is made manifest. I’m thinking that Phantom Sculpture provides a framework within which to witness this crackle, and I have fabricated a scene in my mind in which the holes in Jonathan Baldock’s and Barbara Hepworth’s sculptures move together in the darkness of the Mead Gallery at night, exchanging stories about material reality, spaces that are infused with hope, and the risks that come with being constrained within the assumed boundaries of one’s existence. Further back, in the darkest corner, the sadness that is present in the work of Dominique White, Kira Freije and William Turnbull find a place to rest within the ghostly ruins of humanity’s future.

It can’t seem too fanciful to propose that there are probably more ghosts coalescing around sculpture than any other artform. This may have something to do with the fact that sculpture dances close to the body (its history, after all, tracks the making of monuments and statues) and that ghosts, however immaterial they might be, take up three-dimensional space in our dreams. Unlike paintings or films which create two-dimensional worlds and hug walls and screens as flatness, sculptures are objects that exist in space - we must walk around them with our bodies in order to grasp their entirety, accreting time and varying viewpoints in our wake. This negotiation lends itself to the idea that sculpture has a ghostly aura, an invisible effect that appeals on a visceral, physico-temporal level. In more ways than one, sculpture casts shadows.

How important is it for artists to be visited by these shadows or ghosts of the past? A common mechanism for this type of haunting is the teacher-student relationship, as established in art schools and studios across centuries. (You don’t have to be dead to haunt the next generation). It is important that we have some sense of a story of art, to be able to contribute to, or create a fissure, in its arc. In the group of artists presented here, the ghost of Anthony Caro looms large. His role at the forefront of the ‘New Generation’ working in the 1960s, and as an influential tutor at Central Saint Martins (dubbed the ‘School of Caro’), has earned him a prominent place in the history of 20th century sculpture. (He also taught Kim Lim and, in his later years, Olivia Bax worked as one of his many assistants.) The late, great Phyllida Barlow began her haunting long before she died last year, working for much of her career in isolation, largely unknown and uncelebrated, teaching future generations of artists at The Slade for forty years. She is the link between many UK-based practitioners, including those who have not yet been born.

Half way through the run of Phantom Sculpture, seven artworks were removed and others installed in their place. Apart from being a useful reminder that there are multiple stories of art, this is also an acknowledgement that ghosts are always on the move, shuffling around in the past, present and future, creating schisms, relationships, and provocations across time, space and generations.

Phantom Sculpture

Mead Gallery catalogue text

Jan 2024

They teach us things, these ghosts. Perhaps it’s the same for artists as they navigate the histories of their discipline, sifting through the achievements, projects and failures of those who lived before them, accruing a pile of immaterial bodies and practices that move them, influence them, irritate them, shunt into their work in some way.

For Phantom Sculpture, works of art made over the past sixty years are presented alongside each other - the march of linear time, art historical movements, and accreted, developmental maps are compressed, tantalisingly live, as notes are passed from one generation to the next, whispers gathering across the gallery space. The artists all forge a connection to the British Isles, in that they were either born here, have spent time here, fled from here, or have lived their entire lives here. So, this is a story about the recent history of British sculpture, in all its parochial glory, bombast, dreaming and fragility.

The story contains many other stories, of course, but the dominance of the dominant story is notable for its insistence. The points at which the baton is handed over, dropped, smashed or cherished by artists of different generations, are clearly identifiable as we move, like an Art History undergraduate syllabus, through the decades. From 1950s abstraction, commitment to natural materials and a kind of post-war delirium (Hepworth), to the 1960s when the ‘New Generation’ banished the plinth in order to forge a more democratic relation to the viewer, and employed industrial and synthetic materials to make minimal, conceptual sculptures that resisted monumentality and embraced dematerialisation (Caro). By the 1980s, ‘New British Sculpture’ (always the new) fulfilled the role of recalcitrant child by rejecting their forebearers to produce elemental, sensual or metaphoric imagery, sometimes using traditional processes and materials (Turnbull). Working under the shadow of the Thatcher years, when the burgeoning free-market economy was establishing the tentacled, malign roots of neo-liberalism, these artists often used the debris of contemporary life to play with colour, humour, and variegated forms of physicality.

The 2000’s brought a less easily packaged range of approaches (the nearer we get to the present, the harder it is to identify the characteristics of an era – it takes time to paint out other voices). There’s the introduction of surrealist language, an exploration of the uncanny (Hatoum and Ekks), and an ongoing experimentation with materials and abstraction (Deacon). Bawdy, rule-breaking louchness was celebrated, and the ready-made was employed to celebrate irreverence and humour (Lucas). It was the dawn of a new millennium, we were drunk on the promise of a Labour government and the delusional idea that capitalist growth would deliver a slipstream of comfort for each successive generation. The Iraq War was the beginning of the end of the dream and by the 2010s we were reaching what Mark Fisher (via Franco Berardi) called ‘the slow cancellation of the future’ in which our ability to differentiate the past from the present was compromised by the impact of postmodernity. This ‘temporal bleed’ or ‘dyschromia’ created a strange simultaneity which, Fisher contends, made it hard to locate oneself in a creative present (there is no ‘now’).

And the 2020s? Where have we arrived? Well, every era seems to revel in the construction of its own cataclysmic end-time scenarios, but this decade is promising to deliver a quite spectacular range of possibilities including onanistic globalisation, muscular authoritarianism, aggressive exploitation of labour across and within countries, increasingly desperate refugee flows, social media-propelled right-wing nationalisms, the ongoing delusion of white supremacy, and the obscene, forever expanding chasm dividing the rich from the poor. As I write, the impact of Britain’s rapacious colonial past is rising to meet the present in the horrors that are unfolding in Palestine, Afghanistan, and the Sudan. And, the most cataclysmic cataclysm of them all, the unravelling climate catastrophe. It seems that Fisher underestimated the future of stunted or unrealised futures.

Throughout all of this, art is still made, things need to be said. The artists in Phantom Sculpture deliver a compelling array of disturbing, beautiful, poetic, angry responses to their place in the world. There is a glorious opening up of the range of voices that we are able to hear, reaching beyond the white, predominantly male makeup of recent art historical movements, to welcome the female, the Black, the disabled, the trans, the working class, the Other. Signalling a resounding refusal of old categories and assumptions around what can and can’t be said, there is a synthesis of figuration and abstraction, and a curiosity about the breakdown of binaries between the non-human and human, male and female, machine and organism.

The bombast of previous generations has gone. It has been replaced by fragility, ambiguity and tenderness (Freije, Ackroyd, Buckley, White, and Darling) along with an understanding of impermanence and our entanglement with nature and each other (Lai). There are shape-shifters and mystics in the fray (Baldock and Ekks), as well as unruly bodies that revel in sex and seduction (Ackroyd). Craft, the touch of the hand, the insistence of the power of making, is beautifully evident (Bax, Collings-James, Baldock, and Ryan), as is a scratching at the perversions of consumerism (Wermers). A refusal of Euro-centric modes of knowledge-building and history-making, and a move to create counter-histories, speculative models and forms of resistance are defiantly present (Collings-James, Buckley, Wahid, and White). And there’s an interest in words, language, different ways of making stories through experimental text and collaboration with writers (Bax, Darling, Buckley, Freije). All these approaches and projects, I think, make it easier for artists – and the artworks themselves – to socialise with, and learn from, ghosts. There is an openness, a vulnerability, a seepage into other worlds that conveys a tangible sense that there are many answers to the same question, and that multiple constellations are possible.

But this tidy, art historical narrative, that moves from the 1960s to the present day, obeys the diktats of linear time, and therefore appears to refuse temporal transgressions of ghostly travel across clearly delimited periods - and causal sequences. Maverick art historian Aby Warburg proposed, through his concept of Nachleben, that this disorienting mash-up of eras where images, in their anachronistic, enigmatic, metaphorical state, produce an afterlife that spans and moves through centuries and multiple art historical timeframes, leads to the ‘paradox where the oldest things may appear as less old ones’. Ghosts need to be able to move through time, to party with older, maybe no wiser ghosts, or ones who are new to the scene, just learning the ropes. It seems clear that dreams, lives, and artistic endeavours are not linear, they are fragmented, they fly across situations, centuries and generations. There is a crackle or glitch where time is out of joint, sounds gather and never die, and a cacophonous present is made manifest. I’m thinking that Phantom Sculpture provides a framework within which to witness this crackle, and I have fabricated a scene in my mind in which the holes in Jonathan Baldock’s and Barbara Hepworth’s sculptures move together in the darkness of the Mead Gallery at night, exchanging stories about material reality, spaces that are infused with hope, and the risks that come with being constrained within the assumed boundaries of one’s existence. Further back, in the darkest corner, the sadness that is present in the work of Dominique White, Kira Freije and William Turnbull find a place to rest within the ghostly ruins of humanity’s future.

It can’t seem too fanciful to propose that there are probably more ghosts coalescing around sculpture than any other artform. This may have something to do with the fact that sculpture dances close to the body (its history, after all, tracks the making of monuments and statues) and that ghosts, however immaterial they might be, take up three-dimensional space in our dreams. Unlike paintings or films which create two-dimensional worlds and hug walls and screens as flatness, sculptures are objects that exist in space - we must walk around them with our bodies in order to grasp their entirety, accreting time and varying viewpoints in our wake. This negotiation lends itself to the idea that sculpture has a ghostly aura, an invisible effect that appeals on a visceral, physico-temporal level. In more ways than one, sculpture casts shadows.

How important is it for artists to be visited by these shadows or ghosts of the past? A common mechanism for this type of haunting is the teacher-student relationship, as established in art schools and studios across centuries. (You don’t have to be dead to haunt the next generation). It is important that we have some sense of a story of art, to be able to contribute to, or create a fissure, in its arc. In the group of artists presented here, the ghost of Anthony Caro looms large. His role at the forefront of the ‘New Generation’ working in the 1960s, and as an influential tutor at Central Saint Martins (dubbed the ‘School of Caro’), has earned him a prominent place in the history of 20th century sculpture. (He also taught Kim Lim and, in his later years, Olivia Bax worked as one of his many assistants.) The late, great Phyllida Barlow began her haunting long before she died last year, working for much of her career in isolation, largely unknown and uncelebrated, teaching future generations of artists at The Slade for forty years. She is the link between many UK-based practitioners, including those who have not yet been born.

Half way through the run of Phantom Sculpture, seven artworks were removed and others installed in their place. Apart from being a useful reminder that there are multiple stories of art, this is also an acknowledgement that ghosts are always on the move, shuffling around in the past, present and future, creating schisms, relationships, and provocations across time, space and generations.

Phantom Sculpture

Mead Gallery catalogue text

Jan 2024

VULNERABILITY IS THE THING; THE THING IS VULNERABILITY

Essay for Emscherkunstweg publication. Published by Hatje Cantz, 2023

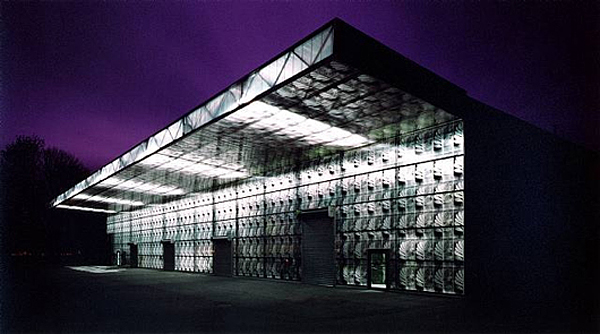

When the curators of the Emscherkunstweg art commissioning programme began discussions with artist Nicole Wermers about making a new work of art for this post-industrial landscape, conversations about potential damage went on for months, if not years. Will the work invite vandalism? Will that vandalism be more or less likely if we install the work here or there? How can we mitigate against this? What type of materials should we use? The list of questions was endless and easily transferable to any number of other public art commissioning contexts. This road of enquiry inevitably leads to a point where we must address whether what we are making is art or just really well constructed, embattled objects in space.

None of these discussions foresaw the fact that when Emscher Folly by Wermers was finally installed in 2022, it was the birds that wreaked havoc on the work, not the kids. Our feathered friends took apparent joy in pecking the bicycle seats, on the hunt for chunks of foam to construct their nests, defying expectations about who, or what, gets to destroy art. Their interaction necessitated the swift replacement of parts of the sculpture with more durable, less bird-enticing options.

What I’d like to discuss here, in this text, is the important role that destruction plays in art commissioning programmes, and how the vulnerability of a work of art is, in my view, intrinsic to its success. The ability of a work to forge a visceral relationship to its public (by which I mean human and non-human) is what gives it its traction. An artwork installed in the public realm is never a static entity - it is a hot-wire to the ever-changing political, social, and environmental contexts in which it is located, and acts as a catalyst for all sorts of engagement and activity, sometimes disturbing or hurtful, at other times joyful or tender.

A charged example of this ever-shifting, often productive terrain is Robert Smithson’s Partially Buried Woodshed which was made in the grounds of Kent State University in January 1970. The artist dumped twenty truckloads of soil onto the central beam of an empty shed until the structure began to crack. His aim was for the shed to ‘go back to the land’ and begin a process of ‘slow destruction’. The conceptual thrust of the work radically changed when members of the National Guard shot at, and killed, four unarmed students protesting at the USA’s involvement in the Vietnam War. This shocking, deeply traumatic event was commemorated on Partially Buried Woodshed with the words ‘MAY 4 KENT 70’ painted on the central beam, presumably by a student - forever linking the work of art and the ‘breaking point’ of the shed to the cultural shift that many consider the Kent State shootings to represent in American history. Much to the irritation of the university authorities, the work has assumed a different relation to its audience, shifting from a conversation around entropy to one that critiques the prevalence of American imperialism, and proselytises the importance of protest and civil defiance.

For public artworks that are destroyed by violent and disturbing aggressors, there may too, be scope for things reborn. When the queer bodies of Nicole Eisenman’s temporary public fountain in Münster were defaced with a Swastika and other offensive imagery in September 2017, the day before Germany elected a far right party to the Bundestag for the first time since World War II, the outrage and upset was palpable. The commissioner (Skulptur Projekte Münster) and the artist were thrown into a press frenzy that stirred up scepticism around contemporary art and its ability to forge a meaningful relation to its public. A group of local women worked with Eisenman to devise an ambitious plan to make a new -permanent - iteration of the work. This grass-roots activity has resulted in the creation of an on-going dialogue with the people of Münster about their city, the role of art in society, and the importance of constructing inclusive spaces for all citizens. In this case, as in many others, destruction became a kind of gathering action in which a space is opened up for the creation of a work that forges a more expansive, powerful relation to the world.