Writing / Columns

Back Space 12.09.03

Building Design, 12 September 2003

Katherine Vaughan Williams (Shonfield) 'Bugger all that Jes, what you really need to do is read Trollope - he's a dream'. This was Kath's response to my dithering over what kind of research I should do for a new job I had at St Paul's Cathedral. And, of course, she was absolutely right. All that infighting disguised as pious good will dulled only by one too many tipples of wine taken at luncheon - Barchester Towers was my set book for the job.

Katherine Vaughan Williams (Shonfield), architect and writer, died of cancer last week. She was 49. She lived with the disease for two and a half years and in true Kath style acted as aggressive host to an unwanted guest: "Those bastards are in my body and I never even invited them!".

I got to know Kath through her membership of the RSA Art for Architecture Advisory Panel which she joined in 1996. What was supposed to be a three year position turned into a seven year one. I just couldn't imagine a meeting without her. She was passionate, infuriating, intensely knowledgeable and hugely vocal. Que.: dodgy slide of dull road in Neasden which receives snorts of high-brow derision from other panel members. Kath, sitting slightly hunched, casting an accusatory eye about the room says 'None of you have got any idea how much work went into that cycle path. Some poor sod went through hell to get that through planning…and you lot just dismiss it like it's crap'. Her stint as a planning officer at Kensington & Chelsea developed her extraordinary ability to see worth in things and ideas that others are blind to.

She'd say all this decked out in the most beautiful garb - her line in posh frocks was truly to be admired. In the most unlikely of ways, she managed to combine a sense of propriety with an aura of convinced sexuality which I think threw most men into a state of total disarray. She was stunning, but of course, the old tart would have none of it; she was so generous in her compliments and as soon as they were fired at her she shooed them away like they were absurd propositions.

In that kind of hip post-feminist, actually-it's-really-nice-to-be-a-mum-and-fuck-up-your-career-for-a-bit, way, Kath went through a phase of calling me (soon after she had had her son Roman) demanding to know when I was going to have a baby. 'Go on Jes, get on with it…just do it, stuff everything else, I promise you won't regret it'.

When I did, finally, obey her command (you couldn't really say no to Kath), she sent me an email on the subject of the social mores involved in child rearing: 'It's basically like the most extreme Trotskyite infighting, or figurative versus abstraction or angels on the head of a pin. And like trotskyism and religion it depends on everyone thinking they are inadequate unless they espouse one or other belief system.' And in response to my concerns over other people's expectations she wrote: 'Oh god, it's actually great; don't let the bastards put the frightners on you. Rosemary's baby - now THERE's something to worry about.'

Kath's death will leave a gaping hole in the field of architecture where women with attitude are few and far between. As a writer, a woman, a lecturer, a friend and colleague, Kath was an inspiration - far more than she was ever aware of. She requested that 'When I'm dead and gone' by McGuinness Flint be played at her funeral; a bit of it goes like this:

When I'm dead and gone

I want to leave some happy woman living on

When I'm dead and gone

Don't want nobody to mourn beside my grave

She's left lots of happy women living on, but we will all morn beside her grave.

Katherine Vaughan Williams (Shonfield), architect and writer, died of cancer last week. She was 49. She lived with the disease for two and a half years and in true Kath style acted as aggressive host to an unwanted guest: "Those bastards are in my body and I never even invited them!".

I got to know Kath through her membership of the RSA Art for Architecture Advisory Panel which she joined in 1996. What was supposed to be a three year position turned into a seven year one. I just couldn't imagine a meeting without her. She was passionate, infuriating, intensely knowledgeable and hugely vocal. Que.: dodgy slide of dull road in Neasden which receives snorts of high-brow derision from other panel members. Kath, sitting slightly hunched, casting an accusatory eye about the room says 'None of you have got any idea how much work went into that cycle path. Some poor sod went through hell to get that through planning…and you lot just dismiss it like it's crap'. Her stint as a planning officer at Kensington & Chelsea developed her extraordinary ability to see worth in things and ideas that others are blind to.

She'd say all this decked out in the most beautiful garb - her line in posh frocks was truly to be admired. In the most unlikely of ways, she managed to combine a sense of propriety with an aura of convinced sexuality which I think threw most men into a state of total disarray. She was stunning, but of course, the old tart would have none of it; she was so generous in her compliments and as soon as they were fired at her she shooed them away like they were absurd propositions.

In that kind of hip post-feminist, actually-it's-really-nice-to-be-a-mum-and-fuck-up-your-career-for-a-bit, way, Kath went through a phase of calling me (soon after she had had her son Roman) demanding to know when I was going to have a baby. 'Go on Jes, get on with it…just do it, stuff everything else, I promise you won't regret it'.

When I did, finally, obey her command (you couldn't really say no to Kath), she sent me an email on the subject of the social mores involved in child rearing: 'It's basically like the most extreme Trotskyite infighting, or figurative versus abstraction or angels on the head of a pin. And like trotskyism and religion it depends on everyone thinking they are inadequate unless they espouse one or other belief system.' And in response to my concerns over other people's expectations she wrote: 'Oh god, it's actually great; don't let the bastards put the frightners on you. Rosemary's baby - now THERE's something to worry about.'

Kath's death will leave a gaping hole in the field of architecture where women with attitude are few and far between. As a writer, a woman, a lecturer, a friend and colleague, Kath was an inspiration - far more than she was ever aware of. She requested that 'When I'm dead and gone' by McGuinness Flint be played at her funeral; a bit of it goes like this:

When I'm dead and gone

I want to leave some happy woman living on

When I'm dead and gone

Don't want nobody to mourn beside my grave

She's left lots of happy women living on, but we will all morn beside her grave.

Back Space 09.08.02

Building Design, 9 August 2002

There are a number of architects' website laws which, I have noticed, are being flouted on an all too frequent basis. Having spent a considerable part of the last month burning the centre of my new laptop monitor onto my retina, surfing the net, I have become an aficionado on the subject. For those of you who are considering giving your website an overhaul here is a list of don'ts:

Don't include flashing pictures, words, shapes, plans, models anywhere - at all - on the site Don't post a black and white photograph of the principal playing piano on the staff profile page (Rafael Vinoly) Don't attempt to make the one female director in your office look like a man on the grounds of uniformity (Nicholas Grimshaw) Don't cover the page in text. Nobody reads it and it hurts your eyes. (Steven Holl) Don't include quotes by your practice chairman which run across the top the page in a pink stripe, followed by quotes from Wittgenstein. (Richard Rogers) Don't make your site so huge that in the time it takes to download, you could make a three course meal and divorce your spouse. (Norman Foster) Don't make the user chase text or images across the page. (Foreign Office Architects) Don't lie about exciting opportunities for newly qualified architects. Much better to come clean: We welcome applications from slaves who have completed their first stage of architectural education and are looking for a stimulating torture chamber in which to complete their practical training. Post applications to: .(JavaScript must be enabled to view this email address). (Foreign Office Architects again) Don't put white text on a black background Don't leave your site to languish at the end of the 20th century, when your new found enthusiasm for building it dried up in 1999. (FAT) Don't use a searing bullet on the news page to spawn competition win details. It looks too much like you need some sex. (Calatrava) Of course, you could always go for the surprising, almost encouraging, 'I couldn't give a fuck' website, a favourite with Zaha Hadid whose site includes a skeletal practice profile and absolutely no working links. Then there's the architects who are so sublime that they have no need for anything so louche as a website (Rem Koolhaas and Herzog & de Meuron). I rather liked the verbose approach from FAT: Read me MORE! it says and 'Click here to become a famous architect'.

But the most simple, engaging and informative site I have come across on my virtual travels is that created by Caruso St John. Recently launched, it does just what I want a website to do. It is informative, beautifully designed and well written. It contains just the right amount of images and it is easy to navigate with its simple organisation of information: 'works' and 'thoughts' - a welcome change from irritating alliteration that comes with 'practice', 'profile' and 'projects'.

I'm sick of staring at a computer screen - I'm off to lie in a dark room with a vodka drip attached to my left eye.

Don't include flashing pictures, words, shapes, plans, models anywhere - at all - on the site Don't post a black and white photograph of the principal playing piano on the staff profile page (Rafael Vinoly) Don't attempt to make the one female director in your office look like a man on the grounds of uniformity (Nicholas Grimshaw) Don't cover the page in text. Nobody reads it and it hurts your eyes. (Steven Holl) Don't include quotes by your practice chairman which run across the top the page in a pink stripe, followed by quotes from Wittgenstein. (Richard Rogers) Don't make your site so huge that in the time it takes to download, you could make a three course meal and divorce your spouse. (Norman Foster) Don't make the user chase text or images across the page. (Foreign Office Architects) Don't lie about exciting opportunities for newly qualified architects. Much better to come clean: We welcome applications from slaves who have completed their first stage of architectural education and are looking for a stimulating torture chamber in which to complete their practical training. Post applications to: .(JavaScript must be enabled to view this email address). (Foreign Office Architects again) Don't put white text on a black background Don't leave your site to languish at the end of the 20th century, when your new found enthusiasm for building it dried up in 1999. (FAT) Don't use a searing bullet on the news page to spawn competition win details. It looks too much like you need some sex. (Calatrava) Of course, you could always go for the surprising, almost encouraging, 'I couldn't give a fuck' website, a favourite with Zaha Hadid whose site includes a skeletal practice profile and absolutely no working links. Then there's the architects who are so sublime that they have no need for anything so louche as a website (Rem Koolhaas and Herzog & de Meuron). I rather liked the verbose approach from FAT: Read me MORE! it says and 'Click here to become a famous architect'.

But the most simple, engaging and informative site I have come across on my virtual travels is that created by Caruso St John. Recently launched, it does just what I want a website to do. It is informative, beautifully designed and well written. It contains just the right amount of images and it is easy to navigate with its simple organisation of information: 'works' and 'thoughts' - a welcome change from irritating alliteration that comes with 'practice', 'profile' and 'projects'.

I'm sick of staring at a computer screen - I'm off to lie in a dark room with a vodka drip attached to my left eye.

Back Space 18.01.02

Building Design, 18 January 2002

'His body leaned back against the sky. It was a body of long straight lines and angles…. He stood, rigid, his hands hanging at his sides, palms out.' Sitting on an aeroplane reading Ayn Rand's The Fountainhead, I realise why it is that it has taken me so long to read this damn book: it's badly written and tortuously long. Written in the style of a blockbuster novel with the political leanings of a Mussolini enthusiast, The Fountainhead is Jeffrey Archer trash for architects.

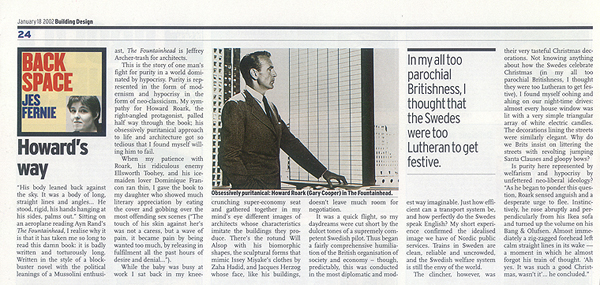

This is the story of one man's fight for purity in a world dominated by hypocrisy. Purity is represented in the form of modernism and hypocrisy in the form of neoclassicsm. My sympathy for Howard Roark, the right-angled protagonist, palled half way through the book; his obsessively puritanical approach to life and architecture got so tedious that I found myself willing him to fail (this seemed to suit him fine too - it did wonders for his sex life). When my patience with Roark, his ridiculous enemy Ellsworth Toohey and his ice-maiden lover Dominique Francon ran thin, I gave the book to my daughter who showed much literary appreciation by eating the cover and gobbing over the most offending sex scenes (The touch of his skin against hers was not a caress, but a wave of pain, it became pain by being wanted too much, by releasing in fulfilment all the past hours of desire and denial...). While the baby was busy at work I sat back in my knee crunching super-economy seat and gathered together in my mind's eye different images of architects, whose characteristics imitate the buildings they produce. There's the rotund Will Alsop with his biomorphic shapes, the sculptural forms mimicking Issay Mayake's clothes worn by Zaha Hadid, and Jacques Herzog whose face, like his buildings, don't leave much room for negotiation.

It was a quick flight, so my daydreams were cut short by the dulcet tones of a supremely competent Swedish pilot. This was just the thin edge of what became for me a very fat wedge of humble pie. Thus began a fairly comprehensive humiliation of the British organisation of society and economy - though, predictably, this was conducted in the most diplomatic and modest way imaginable. Just how efficient can a transport system be and how perfectly do the Swedes speak English? My short experience confirmed the idealised image we have of Nordic public services. Trains in Sweden are clean, reliable and uncrowded, and the Swedish welfare system is still the envy of the world. The clincher, however, was their very tasteful Christmas decorations. Not knowing anything about how the Swedes celebrate Christmas (in my all too parochial Britishness, I thought they were too Lutheran to get festive), I found myself oohing and ahing on our night-time drives: almost every house window was lit with a very simple triangular array of white electric candles. The decorations lining the streets were similarly elegant, with Christmas trees draped in simple, glistening white lights. Why do we Brits insist on littering the streets with revolting jumping Santa Clauses and gloopy bows, all in garish shades of pink, green, red and yellow?

Is purity here represented by welfarism and hypocrisy by unfettered neoliberal ideology? As he began to ponder this question, Roark sensed anguish and a desperate urge to flee. Instinctively, he rose abruptly and perpendicularly from his Ikea sofa and turned up the volume on his Bang & Olufsen. Almost immediately a zigzagged forehead left calm straight lines in its wake -- a moment in which he almost forgot his train of thought. 'Ah yes. It was such a good Christmas, wasn't it'… concluded Roark.

This is the story of one man's fight for purity in a world dominated by hypocrisy. Purity is represented in the form of modernism and hypocrisy in the form of neoclassicsm. My sympathy for Howard Roark, the right-angled protagonist, palled half way through the book; his obsessively puritanical approach to life and architecture got so tedious that I found myself willing him to fail (this seemed to suit him fine too - it did wonders for his sex life). When my patience with Roark, his ridiculous enemy Ellsworth Toohey and his ice-maiden lover Dominique Francon ran thin, I gave the book to my daughter who showed much literary appreciation by eating the cover and gobbing over the most offending sex scenes (The touch of his skin against hers was not a caress, but a wave of pain, it became pain by being wanted too much, by releasing in fulfilment all the past hours of desire and denial...). While the baby was busy at work I sat back in my knee crunching super-economy seat and gathered together in my mind's eye different images of architects, whose characteristics imitate the buildings they produce. There's the rotund Will Alsop with his biomorphic shapes, the sculptural forms mimicking Issay Mayake's clothes worn by Zaha Hadid, and Jacques Herzog whose face, like his buildings, don't leave much room for negotiation.

It was a quick flight, so my daydreams were cut short by the dulcet tones of a supremely competent Swedish pilot. This was just the thin edge of what became for me a very fat wedge of humble pie. Thus began a fairly comprehensive humiliation of the British organisation of society and economy - though, predictably, this was conducted in the most diplomatic and modest way imaginable. Just how efficient can a transport system be and how perfectly do the Swedes speak English? My short experience confirmed the idealised image we have of Nordic public services. Trains in Sweden are clean, reliable and uncrowded, and the Swedish welfare system is still the envy of the world. The clincher, however, was their very tasteful Christmas decorations. Not knowing anything about how the Swedes celebrate Christmas (in my all too parochial Britishness, I thought they were too Lutheran to get festive), I found myself oohing and ahing on our night-time drives: almost every house window was lit with a very simple triangular array of white electric candles. The decorations lining the streets were similarly elegant, with Christmas trees draped in simple, glistening white lights. Why do we Brits insist on littering the streets with revolting jumping Santa Clauses and gloopy bows, all in garish shades of pink, green, red and yellow?

Is purity here represented by welfarism and hypocrisy by unfettered neoliberal ideology? As he began to ponder this question, Roark sensed anguish and a desperate urge to flee. Instinctively, he rose abruptly and perpendicularly from his Ikea sofa and turned up the volume on his Bang & Olufsen. Almost immediately a zigzagged forehead left calm straight lines in its wake -- a moment in which he almost forgot his train of thought. 'Ah yes. It was such a good Christmas, wasn't it'… concluded Roark.

Back Space 30.11.01

Building Design, 30 November 2001

Having made a concerted effort in this column not to mention the fact that I have recently given birth (there is nothing more tedious than hearing other people's baby tales), I can hold out no longer. Contrary to a hitherto held belief that London is a deeply un-child friendly city, I've found, to my astonishment, that rather than feeling isolated and lost in my new found role as 'mother', I have discovered an incredible support network in the form of playgroups, health centre drop-ins and friendly neighbours. Perhaps I'm just very lucky, but the fact that my local council seems to take the issue of child-care and parental support seriously is fantastically helpful. Not so London Transport or those responsible for laying what we should loosely refer to as pavements.

The human capacity to be blind to things, which don't directly affect us, is one constant we can forever rely on. I never paid any heed to the state of pavements when I had nothing to trolley about town on but my own sweet pins. Now that I am an appendage to a pushchair in which my kid lolls and holds court like a Queen, I find that to negotiate the city is to develop aggression tactics and muscles previously unknown to womankind.

Never choosing to travel on the tube at rush hour and not being the owner of a car, I found myself attempting to stagger up the stairs at Oxford Circus at 5.30pm, dragging the throne behind me. On reaching the top, I thanked the man who had walked in tandem with my every step, oblivious to my plight, for not helping me so graciously. He looked blank, shocked and gormless all in one go, and scuttled off to find his self esteem in Tesco's. It seems odd that the transport system relies on the fact that everyone using it should be perfectly mobile and able to negotiate stairs and cramped spaces - particularly because those who rely on it most (those using buses, in particular) are generally the elderly and women with children who are living on low incomes.

Is this a case of 'If men had periods…'? The only London-based initiative that I am aware of which aims to tackle the problem encountered by using a pushchair or wheelchair in the city is the one in Southwark designed by the art and architecture group 'muf'. The uneven paving stones were replaced by a set of beautifully laid sandstones and the width of the pavement was increased to make the road a slightly more pleasurable place to negotiate. But using this stretch of road is like attempting to travel through London on cycle paths: short routes cut off by busy roads, representing nothing but a tantalising taste of what life could be like - if only planners would prioritise anything but car users.

And who the hell designs nappy changing units? I asked an usher at Tate Modern the other day where the baby-changing unit could be found. He pointed in the direction of the women's toilets. The unit was located in a tiny, weird no-man's land between the corridor and the loos where the door constantly slammed. Women entered looking confused, bombarding me with a barrage of questions (Have I got the wrong room? Where are the loos?) while I attempted to negotiate a nappy changing unit which had clearly been designed by a man with the baby skills of a blind childless chimp.

Living in London with a child is like living in heaven and hell: the people, the life, the endless entertainment is sublime, but the road to the people, the life and entertainment is rocky and woe betide anyone who attempts to fight it.

The human capacity to be blind to things, which don't directly affect us, is one constant we can forever rely on. I never paid any heed to the state of pavements when I had nothing to trolley about town on but my own sweet pins. Now that I am an appendage to a pushchair in which my kid lolls and holds court like a Queen, I find that to negotiate the city is to develop aggression tactics and muscles previously unknown to womankind.

Never choosing to travel on the tube at rush hour and not being the owner of a car, I found myself attempting to stagger up the stairs at Oxford Circus at 5.30pm, dragging the throne behind me. On reaching the top, I thanked the man who had walked in tandem with my every step, oblivious to my plight, for not helping me so graciously. He looked blank, shocked and gormless all in one go, and scuttled off to find his self esteem in Tesco's. It seems odd that the transport system relies on the fact that everyone using it should be perfectly mobile and able to negotiate stairs and cramped spaces - particularly because those who rely on it most (those using buses, in particular) are generally the elderly and women with children who are living on low incomes.

Is this a case of 'If men had periods…'? The only London-based initiative that I am aware of which aims to tackle the problem encountered by using a pushchair or wheelchair in the city is the one in Southwark designed by the art and architecture group 'muf'. The uneven paving stones were replaced by a set of beautifully laid sandstones and the width of the pavement was increased to make the road a slightly more pleasurable place to negotiate. But using this stretch of road is like attempting to travel through London on cycle paths: short routes cut off by busy roads, representing nothing but a tantalising taste of what life could be like - if only planners would prioritise anything but car users.

And who the hell designs nappy changing units? I asked an usher at Tate Modern the other day where the baby-changing unit could be found. He pointed in the direction of the women's toilets. The unit was located in a tiny, weird no-man's land between the corridor and the loos where the door constantly slammed. Women entered looking confused, bombarding me with a barrage of questions (Have I got the wrong room? Where are the loos?) while I attempted to negotiate a nappy changing unit which had clearly been designed by a man with the baby skills of a blind childless chimp.

Living in London with a child is like living in heaven and hell: the people, the life, the endless entertainment is sublime, but the road to the people, the life and entertainment is rocky and woe betide anyone who attempts to fight it.

Back Space 07.09.01

Building Design, 7 September 2001

My boyfriend's father came 'round the other day to discover that both lifts in our block had broken and that there was shit in the lobby (human or animal? How d'you tell the difference?) He lives abroad and doesn't come to visit that often, but he had to come on the day that even I felt like packing up and moving to Sussex.

To live in a city or outside a city? That is the question, particularly when you're not endowed with family wealth or a glutinous job in the City. And on mornings like this, I think outside the city is good - yeah, yeah, give me no shit and a transport situation which doesn't include a lift that could form the centre-point in an exhibition on 1970's engineering. Another memorable panic moment like this was the time when my family came 'round for a birthday bash and were spat upon from a great height by loopy, woozy, bored teenagers. My sister and her man decided to take their revenge (quite brave, given the circumstances I thought) by scuttling up to the top of the block and gobbing on them in turn. A few minutes later there was a loud bang on my door: 'I'm gonna get my fuckin' dad on you…my fuckin' shirt is stained, what the fuck are you going to do about it?' Welcome to the neighbourhood.

But then just after a day like that I have a day like this: I get up, the sun is streaming in to my on-high abode and I mentally thank the Lord for the men and women who strove to create a fairer, cleaner world by designing towerblocks from which one can gaze down at all the rich folk in their gloomy two storey shacks. I leave for work and bump into Bill, a neighbour who has lived here since the block was built in 1958. He says he hasn't seen me for a while and where have I been hiding? I tell him that my boyfriend keeps me locked up and only lets me out for special non-occasions. He looks a bit shocked and then smirks and nods his head. In the lift I meet a woman with her two children, both of whom can do nothing but stare, mouths agape, at my unfeasibly long body. 'That's what happens if you eat your greens' the mother says to her children in a sharp but humorous tone. I walk across the grass past the health centre and am greeted with a friendly smile from one of the nurses going in to work. I wave and for the first time ever feel that I am living in a grown up Post Man Pat land, where I play the lead role as Pat's black and white companion in a fluffy, nice world.

The people on Radio 4 who talk about the importance of developing and maintaining 'communities' don't have any idea what a community is because they've never lived in one. Communities in inner city areas only exist where people have pretty crap, tough lives. Stand in any posh persons lift and everybody tries their level best not to make eye contact with their fellow travellers and would never dream of making personal comments about their physical stature.

It's exhausting and exhilarating living in a city. When I've had a gloomy day and come home to share a shaky lift with the dealer up the corridor I feel a strong desire to flee, but where to? A place where the only extremes available to me would be the choice between a Mondeo or a Sierra and where my children would go to school with little suburban racists. No good, stay put; home is where the poo is.

To live in a city or outside a city? That is the question, particularly when you're not endowed with family wealth or a glutinous job in the City. And on mornings like this, I think outside the city is good - yeah, yeah, give me no shit and a transport situation which doesn't include a lift that could form the centre-point in an exhibition on 1970's engineering. Another memorable panic moment like this was the time when my family came 'round for a birthday bash and were spat upon from a great height by loopy, woozy, bored teenagers. My sister and her man decided to take their revenge (quite brave, given the circumstances I thought) by scuttling up to the top of the block and gobbing on them in turn. A few minutes later there was a loud bang on my door: 'I'm gonna get my fuckin' dad on you…my fuckin' shirt is stained, what the fuck are you going to do about it?' Welcome to the neighbourhood.

But then just after a day like that I have a day like this: I get up, the sun is streaming in to my on-high abode and I mentally thank the Lord for the men and women who strove to create a fairer, cleaner world by designing towerblocks from which one can gaze down at all the rich folk in their gloomy two storey shacks. I leave for work and bump into Bill, a neighbour who has lived here since the block was built in 1958. He says he hasn't seen me for a while and where have I been hiding? I tell him that my boyfriend keeps me locked up and only lets me out for special non-occasions. He looks a bit shocked and then smirks and nods his head. In the lift I meet a woman with her two children, both of whom can do nothing but stare, mouths agape, at my unfeasibly long body. 'That's what happens if you eat your greens' the mother says to her children in a sharp but humorous tone. I walk across the grass past the health centre and am greeted with a friendly smile from one of the nurses going in to work. I wave and for the first time ever feel that I am living in a grown up Post Man Pat land, where I play the lead role as Pat's black and white companion in a fluffy, nice world.

The people on Radio 4 who talk about the importance of developing and maintaining 'communities' don't have any idea what a community is because they've never lived in one. Communities in inner city areas only exist where people have pretty crap, tough lives. Stand in any posh persons lift and everybody tries their level best not to make eye contact with their fellow travellers and would never dream of making personal comments about their physical stature.

It's exhausting and exhilarating living in a city. When I've had a gloomy day and come home to share a shaky lift with the dealer up the corridor I feel a strong desire to flee, but where to? A place where the only extremes available to me would be the choice between a Mondeo or a Sierra and where my children would go to school with little suburban racists. No good, stay put; home is where the poo is.

Back Space 27.04.01

Building Design, 27 April 2001

It's irritating being constantly told that the era previous to the one in which you are now living was so much more vibrant and dynamic than the current one. I was born at the arse end of the 60s and grew up in the 1970s and 80s: the void that taste forgot. My parents' record collection (consisting primarily of the Stones, Bob Dylan and Patty Smith) was a constant reminder that I had just missed the good times: my class mates and I were expected to groove to the tunes of the Bay City Rollers and Shawaddywaddy.

There were -- and are -- tasteful exceptions, of course. But, as it happens, I just missed these too. For example, it was just before embarking on my career in the art & architecture world, that the yBa phenomenon exploded onto the scene with Hirst & Co.'s exhibition-cum-marketing ploy Freeze -- a show which rivaled any ad-man's campaign for glory. In a similar way, no sooner did I find out about City Racing (the south London gallery) than it was quickly snuffed out and frozen into an aspic myth for an exhibition at the ICA.

But these are not meant as just so many instances of the all too common existential experience of the 'missed encounter', of the 'grass is greener' syndrome. If these are exceptional moments of vibrancy that I missed, they are also exceptions that prove an all too pervasive rule -- a rule which John Stuart Mill sought to combat in his 19th century On Liberty but which appears to have been experiencing a new lease of life these past three decades or so. This rule dictates quantity, massification, mediocrity.

This was brought home to me by the current Centenary exhibition at the Whitechapel Gallery. In 1956 Bryan Robertson, the then director, held the much mythologised show This is Tomorrow, where a group of artists and architects known (in hindsight) as the Independent Group worked in teams to produce installations. As Le Corbusier put it thirty years previously, these were about 'le synthese des arts'. The atmosphere seemed to be one where risk, a sense of playfulness and even outright antagonism played an intrinsic and scary part of the process. Memorable moments included Erno Goldfinger telling Colin St John Wilson that he was the rudest man he had ever met and a pissed Roger Hilton demanding that Lawrence Alloway and Reyner Banham be expelled from the group: "Get these effing word men out of here!"

At the risk of sounding like an Alsop groupie, I think we now have a situation where people are too busy to play (if not on an Australian beach over a G&T or twelve) and where tick boxes win over curiosity. It is very difficult to imagine a 21st century situation where a local authority architect helps initiate a quirky exhibition in which artists and architects are invited to get it together. (Leslie Martin, head of the department of architecture at the London County Council, played a part in the early development of This is Tomorrow ).

Surprising and productive relationships between artists and architects aren't things that can be legislated for, strictly controlled, defined and monitored; they thrive on a sense of intrigue, serendipity and, as Alloway put it, 'antagonistic co-operation'. This is why the best collaborations come out of small scale, often artist-initiated projects, where analysis and discussion are not lost in the debilitating swill of design meetings at which there is always somebody present who tells you, in great detail, why something is not possible.

To invert Richard Hamilton's contribution to This is Tomorrow:

Just what is it that makes today's culture so different, so unappealing?

There were -- and are -- tasteful exceptions, of course. But, as it happens, I just missed these too. For example, it was just before embarking on my career in the art & architecture world, that the yBa phenomenon exploded onto the scene with Hirst & Co.'s exhibition-cum-marketing ploy Freeze -- a show which rivaled any ad-man's campaign for glory. In a similar way, no sooner did I find out about City Racing (the south London gallery) than it was quickly snuffed out and frozen into an aspic myth for an exhibition at the ICA.

But these are not meant as just so many instances of the all too common existential experience of the 'missed encounter', of the 'grass is greener' syndrome. If these are exceptional moments of vibrancy that I missed, they are also exceptions that prove an all too pervasive rule -- a rule which John Stuart Mill sought to combat in his 19th century On Liberty but which appears to have been experiencing a new lease of life these past three decades or so. This rule dictates quantity, massification, mediocrity.

This was brought home to me by the current Centenary exhibition at the Whitechapel Gallery. In 1956 Bryan Robertson, the then director, held the much mythologised show This is Tomorrow, where a group of artists and architects known (in hindsight) as the Independent Group worked in teams to produce installations. As Le Corbusier put it thirty years previously, these were about 'le synthese des arts'. The atmosphere seemed to be one where risk, a sense of playfulness and even outright antagonism played an intrinsic and scary part of the process. Memorable moments included Erno Goldfinger telling Colin St John Wilson that he was the rudest man he had ever met and a pissed Roger Hilton demanding that Lawrence Alloway and Reyner Banham be expelled from the group: "Get these effing word men out of here!"

At the risk of sounding like an Alsop groupie, I think we now have a situation where people are too busy to play (if not on an Australian beach over a G&T or twelve) and where tick boxes win over curiosity. It is very difficult to imagine a 21st century situation where a local authority architect helps initiate a quirky exhibition in which artists and architects are invited to get it together. (Leslie Martin, head of the department of architecture at the London County Council, played a part in the early development of This is Tomorrow ).

Surprising and productive relationships between artists and architects aren't things that can be legislated for, strictly controlled, defined and monitored; they thrive on a sense of intrigue, serendipity and, as Alloway put it, 'antagonistic co-operation'. This is why the best collaborations come out of small scale, often artist-initiated projects, where analysis and discussion are not lost in the debilitating swill of design meetings at which there is always somebody present who tells you, in great detail, why something is not possible.

To invert Richard Hamilton's contribution to This is Tomorrow:

Just what is it that makes today's culture so different, so unappealing?

Back Space 02.03.01

Building Design, 2nd March 2001

Is there something about having breasts which prevents you from being a successful architect?

Although women make up 50% of students at architecture schools, their staying power within the profession is notoriously short lived. Like many professions, there are his 'n' her career ladders in architecture. The pink one invariably stops in its tracks. Or switches tracks: answering the phone, doing a bit of PR, bringing in the tea -- in short, giving a helping hand to those struggling up the blue ladder.

Standing on the outside of the architecture world, peeking in, you'd think that there was some kind of intrinsic link between mammary glands and telephone reception skills. On the few occasions that I have called an architecture practice and been greeted with a man's voice, it is clear that he is there because a woman has temporarily left her post as 'practice receptionist'. These men usually pride themselves on the fact that they are unable to find a pen, apply it to paper, check a fact, transfer my call; they're just too damn creative / busy / important for that sort of thing. And besides, Sophia (the qualified architect) will be back in a moment to help with your enquiry.

Why are there so few successful female architects heading up their own practices? I could roll out a host of reasons, from anti-social working hours to evolutionary psychology twaddle, but I'd put my money on the ego hypothesis. Boys are encouraged by their mothers to develop a premature confidence in their own actions and ideas, while girls tend to fortify their idea of themselves or their actions indirectly through the desires of others. It is a well-known fact that mothers dote more on their sons than on their daughters: 'studies show that mothers breast feed their male children 70 percent longer than their female children' (Bruce Fink). This means that boys are encouraged to feel that they lack something which they must constantly strive to fill. Hence their focus on themselves. While girls are much more sensitive to what others want. (This observation, of course, has the added benefit of explaining how men can live in squalor: '... because all their narcissism has been focused on themselves, on their own ego: hence they can be oblivious to the state of their apartment.' (Darian Leader)

To be a successful, big shot architect today, therefore, you must have a padded ego. You must believe in yourself to the virtual exclusion of all others. You have to fulfil the client's idea of what an architect is (creative, compulsive, difficult etc) and it helps if you are a show off. The one woman's name which constantly crops up among the roll call of super star architects is Zaha Hadid. Rem Koolhaas, Renzo Piano, Norman Foster, Jacque Herzog, Daniel Liebeskind and Zaha Hadid. And everybody knows that she Queen of Strop.

It's a serious drawback that women won't bloody speak in public. Success in architecture requires the creation of a public persona and the selling of dreams. It's not good enough just to beaver away in your back room hoping that somebody will notice your talent. You have to stand on a platform and perform. I have been to so many lectures given by members of architectural practices which are made up of a female / male partnership where the bloke stands up, talks loudly and audibly for all to hear and where a whimper from the sidelines constitutes the contribution of the female partner. Why? Lord knows, you don't have to be particularly good at it -- people will attend the most tedious of lectures just to imbibe a wisp of the master's genius. Anyone who sat through Roger Diener's lecture at the AA last week will know exactly what I'm talking about.

Although women make up 50% of students at architecture schools, their staying power within the profession is notoriously short lived. Like many professions, there are his 'n' her career ladders in architecture. The pink one invariably stops in its tracks. Or switches tracks: answering the phone, doing a bit of PR, bringing in the tea -- in short, giving a helping hand to those struggling up the blue ladder.

Standing on the outside of the architecture world, peeking in, you'd think that there was some kind of intrinsic link between mammary glands and telephone reception skills. On the few occasions that I have called an architecture practice and been greeted with a man's voice, it is clear that he is there because a woman has temporarily left her post as 'practice receptionist'. These men usually pride themselves on the fact that they are unable to find a pen, apply it to paper, check a fact, transfer my call; they're just too damn creative / busy / important for that sort of thing. And besides, Sophia (the qualified architect) will be back in a moment to help with your enquiry.

Why are there so few successful female architects heading up their own practices? I could roll out a host of reasons, from anti-social working hours to evolutionary psychology twaddle, but I'd put my money on the ego hypothesis. Boys are encouraged by their mothers to develop a premature confidence in their own actions and ideas, while girls tend to fortify their idea of themselves or their actions indirectly through the desires of others. It is a well-known fact that mothers dote more on their sons than on their daughters: 'studies show that mothers breast feed their male children 70 percent longer than their female children' (Bruce Fink). This means that boys are encouraged to feel that they lack something which they must constantly strive to fill. Hence their focus on themselves. While girls are much more sensitive to what others want. (This observation, of course, has the added benefit of explaining how men can live in squalor: '... because all their narcissism has been focused on themselves, on their own ego: hence they can be oblivious to the state of their apartment.' (Darian Leader)

To be a successful, big shot architect today, therefore, you must have a padded ego. You must believe in yourself to the virtual exclusion of all others. You have to fulfil the client's idea of what an architect is (creative, compulsive, difficult etc) and it helps if you are a show off. The one woman's name which constantly crops up among the roll call of super star architects is Zaha Hadid. Rem Koolhaas, Renzo Piano, Norman Foster, Jacque Herzog, Daniel Liebeskind and Zaha Hadid. And everybody knows that she Queen of Strop.

It's a serious drawback that women won't bloody speak in public. Success in architecture requires the creation of a public persona and the selling of dreams. It's not good enough just to beaver away in your back room hoping that somebody will notice your talent. You have to stand on a platform and perform. I have been to so many lectures given by members of architectural practices which are made up of a female / male partnership where the bloke stands up, talks loudly and audibly for all to hear and where a whimper from the sidelines constitutes the contribution of the female partner. Why? Lord knows, you don't have to be particularly good at it -- people will attend the most tedious of lectures just to imbibe a wisp of the master's genius. Anyone who sat through Roger Diener's lecture at the AA last week will know exactly what I'm talking about.