Writing / Articles

Flood House interview

Pea Proposals, July 2016

pea proposals talks to Jes Fernie about the Flood House project

June 2016

Pea Proposals: There's a long history of 'the social' in public art making - Ruskin's Road, Watts Chapel being early examples. Socially engaged practice was particularly celebrated in the 1990s and this non-object based form of art practice has been prevalent for some 20 years. pea proposals perceive a return to the art object and we are curious as to what the impacts of social engagement can bring to this turnaround. Flood House is an interesting object to consider in this way, and we would like to hear your thoughts...

Jes Fernie: After twenty years of socially engaged practice that involves lots of really interesting conversations, terrible photos, fluid processes and no fixed outcome, I now feel a huge sense of catharsis when I see a William Mitchell mural that is solid, beautiful and convinced. I can locate his works within a particular timeframe in British history - a post-war euphoria where the generosity of spirit in the public realm was tangible.

It's not that socially engaged projects have been replaced by the object, but rather there seems to be an openness to considering all types of practice that might encompass performance, architecture, the voice, poetry and literature, as well as sculpture and objects more traditionally though of as 'art'. Conversations about 'public space' and 'social engagement' seem pretty antiquated now that space and engagement involves a multitude of different platforms and types (digital, privatised, virtual etc).

The Flood House programme is part of this turn and encompasses sculpture, performance and literature. The structure itself is a physical object that takes up space and moves through the Thames Estuary - although I wouldn't position the structure as art, it is very much an architectural proposition, designed by Matthew Butcher using the language of architecture. Ruth Ewan's weathervane (positioned on the roof of Flood House) was made by a specialist maker in Wales. Ruth drew on her long-term interest in histories of utopian thought to make a work that referenced the 14th c. radical Essex priest John Ball and his commitment to leveling out the entrenched hierarchies and inequality that existed in British society (and of course still exist today, 600 years later).

In a way, it's a remarkably retro type of commission in that it's a stand-alone work for a pre-existing architectural structure, and that feels very liberating! Ruth's response was so simple and direct (the introduction of the palindromic word 'LEVEL' on the east / west axis of the weathervane), it didn't require a whole host of workshops, participatory conversations to make it happen. I think that's what's changed - we've become more confident in our commissioning methodologies, drawing on a whole range of working practices and responses that are honed to the specific nature of a project.

As well as this physical object (the weathervane), we also commissioned a fiction writer to write a story about a notional inhabitant of Flood House. As the project didn't offer a participatory, immersive experience, we wanted to find a way that people could project themselves into the narrative of the structure (more about this below).

A performative element of the programme entered the frame at the launch. We invited a choir from Brixton to sing a folk song about John Ball at Southend Pier, with Flood House floating behind them. It was a pretty special event, which I hope engaged audiences on an experiential and emotional level.

So, to sum up, I think what's new is this mix of performative, object-based artistic and curatorial practice that extends into literature and the written word. I've just read Claire Bishop's essay 'Black Box, White Cube, Public Space' commissioned by Skulpture Project Munster, about the recent surge in the number of performances in gallery spaces - that's probably for another conversation, but there are connections with the public realm and the privatisation of public space that are pertinent here.

PP: Art and Architecture come together in Flood House. Could you tell me something about the evolving conversation between the two disciplines, with particular reference to Flood House? I'd also be interested to hear how your work at the Royal Society of Arts on the Art and Architecture programme might have informed this project?

I spent the late 90s and early 00s talking endlessly about 'seamless collaborations' between artists and architects where the final result wouldn't necessarily be physically evident to the viewer. That school of thought came out of two decades of low-grade public art commissioning that involved ill-conceived, hastily commissioned artwork in civic spaces. There was a push to recognise that ideas and conversations were what was important - a constructive dialogue between architect and artist that extended the parameters of their disciplines and would, perhaps, become visually present the architecture of a building or the design of a public space. In a similar way that teenagers often reject their parents' life choices, then as they get older they find common ground and recognise the worth in the older generation's viewpoints, art commissioning has matured, extended and developed significantly over the last ten years, in line with conversations about expanded practice, new types of space (privatised, digital etc) and politicised contexts (developments of neo-liberal policies, funding mechanisms etc). I think this is a really exciting development.

PP: I am interested in the range of commissions at Flood House, in the role that the short story plays, in how you came to appoint the writer and how much she was introduced to the project prior to writing. In what sense is the story element, along with Ruth Ewen's beautiful weather vane, collaborations or independent artworks?

JF: After years of keeping my interest in literature and art separate, I managed to bring them together for Flood House. I spent the most incredible day walking from Leigh-on-Sea to Two Tree Island in Essex with Joanna Quinn (Flood House writer) talking about mud and forgotten female authors. For me, it's been the most exciting element of the programme (along with the political angle that Ruth bought) and it's something I'd love to develop in future curatorial projects.

I wanted to find a way creating a space for people to inhabit Flood House imaginatively - to project themselves into a near dystopic future in which water levels have risen and where people live in hostile environments, scavenging for equipment and food. I'm a big White Review fan - as is Matthew - so we contacted the magazine's editor Ben Eastham to ask if he could recommend any fiction writers we might consider working with. He gave me a list and when I read a story by Joanna that had a sharp, feminist narrative about a woman who is denied the chance of going out to sea, I knew immediately I'd found our writer.

All of the works - Flood House, the weathervane and Mudlark - come out of the Flood House narrative, which was first developed by Matthew eight years ago, but they also stand alone as distinct works. The brilliant staff at Focal Point Gallery who commissioned the weathervane are now looking for sites in Southend for the permanent relocation of the weathervane. We'd love it to be located in an organisation that is connected to the idea of liberty, political action or radicalism in some form. We're also considering ways of positioning Joanna's story in different contexts to bring it to a wider audience (book festivals in Essex is a current thought); and Flood House may move on to new shores to become a catalyst for further commissions and conversations about climate change and architecture.

June 2016

Pea Proposals: There's a long history of 'the social' in public art making - Ruskin's Road, Watts Chapel being early examples. Socially engaged practice was particularly celebrated in the 1990s and this non-object based form of art practice has been prevalent for some 20 years. pea proposals perceive a return to the art object and we are curious as to what the impacts of social engagement can bring to this turnaround. Flood House is an interesting object to consider in this way, and we would like to hear your thoughts...

Jes Fernie: After twenty years of socially engaged practice that involves lots of really interesting conversations, terrible photos, fluid processes and no fixed outcome, I now feel a huge sense of catharsis when I see a William Mitchell mural that is solid, beautiful and convinced. I can locate his works within a particular timeframe in British history - a post-war euphoria where the generosity of spirit in the public realm was tangible.

It's not that socially engaged projects have been replaced by the object, but rather there seems to be an openness to considering all types of practice that might encompass performance, architecture, the voice, poetry and literature, as well as sculpture and objects more traditionally though of as 'art'. Conversations about 'public space' and 'social engagement' seem pretty antiquated now that space and engagement involves a multitude of different platforms and types (digital, privatised, virtual etc).

The Flood House programme is part of this turn and encompasses sculpture, performance and literature. The structure itself is a physical object that takes up space and moves through the Thames Estuary - although I wouldn't position the structure as art, it is very much an architectural proposition, designed by Matthew Butcher using the language of architecture. Ruth Ewan's weathervane (positioned on the roof of Flood House) was made by a specialist maker in Wales. Ruth drew on her long-term interest in histories of utopian thought to make a work that referenced the 14th c. radical Essex priest John Ball and his commitment to leveling out the entrenched hierarchies and inequality that existed in British society (and of course still exist today, 600 years later).

In a way, it's a remarkably retro type of commission in that it's a stand-alone work for a pre-existing architectural structure, and that feels very liberating! Ruth's response was so simple and direct (the introduction of the palindromic word 'LEVEL' on the east / west axis of the weathervane), it didn't require a whole host of workshops, participatory conversations to make it happen. I think that's what's changed - we've become more confident in our commissioning methodologies, drawing on a whole range of working practices and responses that are honed to the specific nature of a project.

As well as this physical object (the weathervane), we also commissioned a fiction writer to write a story about a notional inhabitant of Flood House. As the project didn't offer a participatory, immersive experience, we wanted to find a way that people could project themselves into the narrative of the structure (more about this below).

A performative element of the programme entered the frame at the launch. We invited a choir from Brixton to sing a folk song about John Ball at Southend Pier, with Flood House floating behind them. It was a pretty special event, which I hope engaged audiences on an experiential and emotional level.

So, to sum up, I think what's new is this mix of performative, object-based artistic and curatorial practice that extends into literature and the written word. I've just read Claire Bishop's essay 'Black Box, White Cube, Public Space' commissioned by Skulpture Project Munster, about the recent surge in the number of performances in gallery spaces - that's probably for another conversation, but there are connections with the public realm and the privatisation of public space that are pertinent here.

PP: Art and Architecture come together in Flood House. Could you tell me something about the evolving conversation between the two disciplines, with particular reference to Flood House? I'd also be interested to hear how your work at the Royal Society of Arts on the Art and Architecture programme might have informed this project?

I spent the late 90s and early 00s talking endlessly about 'seamless collaborations' between artists and architects where the final result wouldn't necessarily be physically evident to the viewer. That school of thought came out of two decades of low-grade public art commissioning that involved ill-conceived, hastily commissioned artwork in civic spaces. There was a push to recognise that ideas and conversations were what was important - a constructive dialogue between architect and artist that extended the parameters of their disciplines and would, perhaps, become visually present the architecture of a building or the design of a public space. In a similar way that teenagers often reject their parents' life choices, then as they get older they find common ground and recognise the worth in the older generation's viewpoints, art commissioning has matured, extended and developed significantly over the last ten years, in line with conversations about expanded practice, new types of space (privatised, digital etc) and politicised contexts (developments of neo-liberal policies, funding mechanisms etc). I think this is a really exciting development.

PP: I am interested in the range of commissions at Flood House, in the role that the short story plays, in how you came to appoint the writer and how much she was introduced to the project prior to writing. In what sense is the story element, along with Ruth Ewen's beautiful weather vane, collaborations or independent artworks?

JF: After years of keeping my interest in literature and art separate, I managed to bring them together for Flood House. I spent the most incredible day walking from Leigh-on-Sea to Two Tree Island in Essex with Joanna Quinn (Flood House writer) talking about mud and forgotten female authors. For me, it's been the most exciting element of the programme (along with the political angle that Ruth bought) and it's something I'd love to develop in future curatorial projects.

I wanted to find a way creating a space for people to inhabit Flood House imaginatively - to project themselves into a near dystopic future in which water levels have risen and where people live in hostile environments, scavenging for equipment and food. I'm a big White Review fan - as is Matthew - so we contacted the magazine's editor Ben Eastham to ask if he could recommend any fiction writers we might consider working with. He gave me a list and when I read a story by Joanna that had a sharp, feminist narrative about a woman who is denied the chance of going out to sea, I knew immediately I'd found our writer.

All of the works - Flood House, the weathervane and Mudlark - come out of the Flood House narrative, which was first developed by Matthew eight years ago, but they also stand alone as distinct works. The brilliant staff at Focal Point Gallery who commissioned the weathervane are now looking for sites in Southend for the permanent relocation of the weathervane. We'd love it to be located in an organisation that is connected to the idea of liberty, political action or radicalism in some form. We're also considering ways of positioning Joanna's story in different contexts to bring it to a wider audience (book festivals in Essex is a current thought); and Flood House may move on to new shores to become a catalyst for further commissions and conversations about climate change and architecture.

Keeping to the Path, Simon Pope and Jes Fernie

engage 29, 2012: Art and the Olympics

Bombyx Mori

Interview with Simon Periton in catalogue for permanent firstsite commission Bombyx Mori, 2012

Did Someone Say ‘Get Wet?’

Blueprint, October 2008

What is this itch I have about my ankles? Oh, here's another at my elbow and another, priming itself on my nose. Ah! It's a pavilion; a temporary structure made by an architect, or an artist or possibly both.

As Tim Abrahams reported in a recent Blueprint article, there were no less than twenty pavilions scattered across London this summer, many brought to us courtesy of the hugely successful London Festival of Architecture. And like a germ on a mission to procreate they continue to multiply. Frank Gehry's ode to vanity at the Serpentine Gallery; the 'Portavilion' structures in parks across London by Toby Paterson, Dan Graham, Annika Eriksson and Monika Sosnowska; Jeppe Hein's 'Appearing Rooms' outside the Royal Festival Hall; and more further afield the pavilion in Osterlen, Sweden by David Chipperfield and Antony Gormley (another type of deadly rash currently spreading across the western world).

It all started when I took my kids on a trip around London on a sleepy Saturday morning. We began at the Southwark Lido, the French collective EXYZT's ode to city living where the sun didn't shine but we had a pleasant time hanging out on deck chairs talking to people like us who were watching the children of people like us being ritualistically cleansed in the pool in front of us. Dishevelled, insouciant French architects were lounging around in beach huts looking very much as if the 'participation' bit of their project was something they engaged in last night rather than this morning.

Slightly soggy but light-hearted and gay, we made our way up to the South Bank to see the Psycho Buildings show at the Hayward. Oh no! A long queue. But no matter, here is a temporary structure to distract the kids from the trauma of 21st century cultural consumption. Jeppe Hein's 'Appearing Rooms' is a thrill a minute. Quick! Run into the empty room while the water spurts are low. Marvel at your entrapment when the spurts rise again.

Clothes now thoroughly sodden, we pad off to steam dry in Tomas Saraceno's 'Observatory, Air-port-city', the Buckminster-Fuller-type transparent dome located on one of the Hayward's sculpture terraces. We lounge around in a soporific state of hazy non-participation, vaguely computing that there are human bodies traversing the dome above our heads. We shuffle to another sculpture terrace where we witness the surreal scene of people indulging in the fantasy of living a bucolic life rowing into an inner-city sunset on an artificial lake, courtesy of the Austrian artist collective Gelitin.

It was a day of physical and immersive play which got me thinking about what is happening in our public realm, how art and architecture are increasingly being used as a tool to engage, involve and 'challenge' audiences.

There are a number of themes that these artists and architects seem to be interested in exploring:

- How to make a social structure which somehow engages the audience in a meaningful or participatory way;

- How to challenge people's perceptions of their environment;

- How human behaviour and social norms influence the way we inhabit and negotiate public space;

- How collaboration with specialists working in different fields and public agencies can open up fruitful dialogues and engage new audiences.

What I'm interested in is whether these projects are doing anything more than providing an opportunity to bring people together, to create a good atmosphere and get strangers talking to each other. Or do they have more bite: are they able to create a platform for dissent; a critique of contemporary politics and institutions or a platform for real social change? Or, to put it another way, is there a void where once there was political dissent or action? As Dave Beech asks in a recent essay published in Art Monthly, is there a declining ambition for the politics of participation? Is the participant merely invited to accept the parameters of an art project rather than assume the role of subversive agent?

Do we go so far as Derrida who says that inclusion is a brand of neutralisation? Probably not, but extremes can sometimes be useful to construct a critical framework.

How much is the government's agenda to involve new audiences in contemporary culture related to this explosion of activity in the public realm and participatory art and architecture projects?

What is the relationship to this expansion of artistic practice and the increasing privatisation of the public realm?

What does 'temporary' allow for that 'permanent' is unable to offer? Is our obsession with temporariness linked to the capitalist drive to make us forget - to consume more tomorrow?

Or is this interest in temporary architectural structures related to a growing fascination with the intersection of the public and the private; the permeability of exterior and interior spaces or what the critical theorist Giuliana Bruno refers to, with particular reference to the work of Rachel Whiteread, as 'the definition of the frame of memory'?

What relationship does the institution, in particular, the art gallery, have to the public realm? Is the expanding number of off-site programmes and art and architecture biennials which take the city as a starting point for discussion, an instrumentalisation of art and architecture or a welcome implosion of the gallery walls?

And finally, is this activity indicative of a general move towards 'easy art' or the public realm equivalent of Julian Stallabrass' highartlite. A sort of immerse-yourself-in-a-physical-or-social-situation-and-forget-the-rest type of hedonism or do these projects provoke serious questions for those who interact with them?

I am genuinely unable to make up my mind where I stand on this issue. On the one hand, these structures quite clearly enliven our streets and create extraordinary opportunities for artists and architects to play a part in shaping our public realm and it seems churlish to bash that. But I can't help thinking that more subversion, dirt and dissonance needs to be bred into these structures; we need more public realm equivalents of Velvet Underground's 'Venus in Furs'.

As Tim Abrahams reported in a recent Blueprint article, there were no less than twenty pavilions scattered across London this summer, many brought to us courtesy of the hugely successful London Festival of Architecture. And like a germ on a mission to procreate they continue to multiply. Frank Gehry's ode to vanity at the Serpentine Gallery; the 'Portavilion' structures in parks across London by Toby Paterson, Dan Graham, Annika Eriksson and Monika Sosnowska; Jeppe Hein's 'Appearing Rooms' outside the Royal Festival Hall; and more further afield the pavilion in Osterlen, Sweden by David Chipperfield and Antony Gormley (another type of deadly rash currently spreading across the western world).

It all started when I took my kids on a trip around London on a sleepy Saturday morning. We began at the Southwark Lido, the French collective EXYZT's ode to city living where the sun didn't shine but we had a pleasant time hanging out on deck chairs talking to people like us who were watching the children of people like us being ritualistically cleansed in the pool in front of us. Dishevelled, insouciant French architects were lounging around in beach huts looking very much as if the 'participation' bit of their project was something they engaged in last night rather than this morning.

Slightly soggy but light-hearted and gay, we made our way up to the South Bank to see the Psycho Buildings show at the Hayward. Oh no! A long queue. But no matter, here is a temporary structure to distract the kids from the trauma of 21st century cultural consumption. Jeppe Hein's 'Appearing Rooms' is a thrill a minute. Quick! Run into the empty room while the water spurts are low. Marvel at your entrapment when the spurts rise again.

Clothes now thoroughly sodden, we pad off to steam dry in Tomas Saraceno's 'Observatory, Air-port-city', the Buckminster-Fuller-type transparent dome located on one of the Hayward's sculpture terraces. We lounge around in a soporific state of hazy non-participation, vaguely computing that there are human bodies traversing the dome above our heads. We shuffle to another sculpture terrace where we witness the surreal scene of people indulging in the fantasy of living a bucolic life rowing into an inner-city sunset on an artificial lake, courtesy of the Austrian artist collective Gelitin.

It was a day of physical and immersive play which got me thinking about what is happening in our public realm, how art and architecture are increasingly being used as a tool to engage, involve and 'challenge' audiences.

There are a number of themes that these artists and architects seem to be interested in exploring:

- How to make a social structure which somehow engages the audience in a meaningful or participatory way;

- How to challenge people's perceptions of their environment;

- How human behaviour and social norms influence the way we inhabit and negotiate public space;

- How collaboration with specialists working in different fields and public agencies can open up fruitful dialogues and engage new audiences.

What I'm interested in is whether these projects are doing anything more than providing an opportunity to bring people together, to create a good atmosphere and get strangers talking to each other. Or do they have more bite: are they able to create a platform for dissent; a critique of contemporary politics and institutions or a platform for real social change? Or, to put it another way, is there a void where once there was political dissent or action? As Dave Beech asks in a recent essay published in Art Monthly, is there a declining ambition for the politics of participation? Is the participant merely invited to accept the parameters of an art project rather than assume the role of subversive agent?

Do we go so far as Derrida who says that inclusion is a brand of neutralisation? Probably not, but extremes can sometimes be useful to construct a critical framework.

How much is the government's agenda to involve new audiences in contemporary culture related to this explosion of activity in the public realm and participatory art and architecture projects?

What is the relationship to this expansion of artistic practice and the increasing privatisation of the public realm?

What does 'temporary' allow for that 'permanent' is unable to offer? Is our obsession with temporariness linked to the capitalist drive to make us forget - to consume more tomorrow?

Or is this interest in temporary architectural structures related to a growing fascination with the intersection of the public and the private; the permeability of exterior and interior spaces or what the critical theorist Giuliana Bruno refers to, with particular reference to the work of Rachel Whiteread, as 'the definition of the frame of memory'?

What relationship does the institution, in particular, the art gallery, have to the public realm? Is the expanding number of off-site programmes and art and architecture biennials which take the city as a starting point for discussion, an instrumentalisation of art and architecture or a welcome implosion of the gallery walls?

And finally, is this activity indicative of a general move towards 'easy art' or the public realm equivalent of Julian Stallabrass' highartlite. A sort of immerse-yourself-in-a-physical-or-social-situation-and-forget-the-rest type of hedonism or do these projects provoke serious questions for those who interact with them?

I am genuinely unable to make up my mind where I stand on this issue. On the one hand, these structures quite clearly enliven our streets and create extraordinary opportunities for artists and architects to play a part in shaping our public realm and it seems churlish to bash that. But I can't help thinking that more subversion, dirt and dissonance needs to be bred into these structures; we need more public realm equivalents of Velvet Underground's 'Venus in Furs'.

Platform for Art

Blueprint, October 2007

It is a hundred years since Frank Pick, Publicity Officer at London Underground, launched an art commissioning programme for posters on the tube. By the 1920's forty posters a year by unknown artists and big names such as Graham Sutherland and Man Ray, were prominently displayed, making the tube system one of the biggest public galleries in the world. Each work was judged by Pick on the basis of its 'fitness for purpose', by which, it is presumed, he meant the effectiveness of the image to speak to the masses.

The 'fitness for purpose' of the Underground's current commissioning programme is fabulously exploded in that it now encompasses performances, food tasting binges, oyster wallet designs and podcasts of wildlife recordings. But however diverse the programme now is, the air of respect coupled with nostalgia for London Underground continues to seep into many of the works. This is most evident in the cover for the most recent Pocket Tube Map, designed by artists Jeremy Deller (he of Turner Prize fame) and Paul Ryan. A delicate, deeply un-fashionable line-drawn portrait of John Hough, a London Underground employee who has worked for the Underground since 1967, celebrates the period in English society when a sense of vocation was both economically and socially viable.

The poster design for Brian Griffith's year-long installation at Gloucester Road station makes clever use of Edward Johnston's iconic sans serif typeface (also commissioned by Frank Pick), creating another link with the history of art and design produced for the Underground. Griffiths' work, Life is a Laugh, is an insanely bold installation which challenges any lover of art-by-numbers to stand up and be reckoned with. His 70 meter long, site specific work consists of, amongst other things, a giant panda head, a caravan, a collection of ladders and a lamppost rescued from the M42. It is a visual manifestation of his audience's mindset as they make their way to and from work; a doodle consisting of seemingly abandoned detritus from a fairground for the insane.

There aren't many examples of art commissioning programmes for transport systems which reach beyond the desire to prettify a dark hollow or simply distract the audience from the actuality of its situation. The overwhelming array of sculptures, mosaics, paintings, installations and reliefs installed in 90 of the 100 stations that make up the Stockholm Metro verges on the oppressive: look! It's art - appreciate it! North American cities such as New York and Los Angeles have schizophrenic programmes which veer from contemporary realist paintings on subway walls depicting everyday city life (Eric Fischl for New York's MTA Art in Transit programme) to photographs which provide a critique of contemporary culture (Colette Fu for the LA Metro). Although this something-for-everyone approach may seem to be a more democratic way of presenting art in the public realm, the lack of a curatorial eye means that a murky soup is made where conviction can gain no foothold.

Most Platform for Art commissions are temporary rather than permanent, which might be argued, allows the artists and audience to enter into a dialogue that is dynamic and open ended. While this reflects much activity in the realm of contemporary commissioning (consider the Fouth Plinth initiative in Trafalgar Square and all of Artangel's projects) does this equate to a 21st century fear of commitment? Fear on the part of the artist who is nervous about presenting a work which soon dates or perhaps lack of conviction by Transport for London regarding the benefits of art in their midst (temporary projects are much cheaper and easier to manage after all)? Eduardo Paolozzi's mosaic at Tottenham Court Road, now twenty five years old, is for many, a good example of how a permanent work of art can relatively quickly inhabit a covetous place in the popular mindset of its audience. Images of city life are realised in the form of rushing commuters, masks from the nearby British Museum, blaring saxophones mimicking the presence of buskers and abstract patterns exuding a vibrant sense of movement.

While the effectiveness and formal qualities of Paolozzi's work cannot be denied, its ability to do anything more than provide a backdrop to a city limits its scope. People like it because they feel safe with it; it is a recognisable land mark which is beautifully conceived and crafted. But really good art and bold commissioning goes further than this. By presenting artists and audiences with an exploratory space in which they can capitalise on the strangely static feeling that comes with the actions of leaving and arriving, Platform for Art strives to do just this.

The 'fitness for purpose' of the Underground's current commissioning programme is fabulously exploded in that it now encompasses performances, food tasting binges, oyster wallet designs and podcasts of wildlife recordings. But however diverse the programme now is, the air of respect coupled with nostalgia for London Underground continues to seep into many of the works. This is most evident in the cover for the most recent Pocket Tube Map, designed by artists Jeremy Deller (he of Turner Prize fame) and Paul Ryan. A delicate, deeply un-fashionable line-drawn portrait of John Hough, a London Underground employee who has worked for the Underground since 1967, celebrates the period in English society when a sense of vocation was both economically and socially viable.

The poster design for Brian Griffith's year-long installation at Gloucester Road station makes clever use of Edward Johnston's iconic sans serif typeface (also commissioned by Frank Pick), creating another link with the history of art and design produced for the Underground. Griffiths' work, Life is a Laugh, is an insanely bold installation which challenges any lover of art-by-numbers to stand up and be reckoned with. His 70 meter long, site specific work consists of, amongst other things, a giant panda head, a caravan, a collection of ladders and a lamppost rescued from the M42. It is a visual manifestation of his audience's mindset as they make their way to and from work; a doodle consisting of seemingly abandoned detritus from a fairground for the insane.

There aren't many examples of art commissioning programmes for transport systems which reach beyond the desire to prettify a dark hollow or simply distract the audience from the actuality of its situation. The overwhelming array of sculptures, mosaics, paintings, installations and reliefs installed in 90 of the 100 stations that make up the Stockholm Metro verges on the oppressive: look! It's art - appreciate it! North American cities such as New York and Los Angeles have schizophrenic programmes which veer from contemporary realist paintings on subway walls depicting everyday city life (Eric Fischl for New York's MTA Art in Transit programme) to photographs which provide a critique of contemporary culture (Colette Fu for the LA Metro). Although this something-for-everyone approach may seem to be a more democratic way of presenting art in the public realm, the lack of a curatorial eye means that a murky soup is made where conviction can gain no foothold.

Most Platform for Art commissions are temporary rather than permanent, which might be argued, allows the artists and audience to enter into a dialogue that is dynamic and open ended. While this reflects much activity in the realm of contemporary commissioning (consider the Fouth Plinth initiative in Trafalgar Square and all of Artangel's projects) does this equate to a 21st century fear of commitment? Fear on the part of the artist who is nervous about presenting a work which soon dates or perhaps lack of conviction by Transport for London regarding the benefits of art in their midst (temporary projects are much cheaper and easier to manage after all)? Eduardo Paolozzi's mosaic at Tottenham Court Road, now twenty five years old, is for many, a good example of how a permanent work of art can relatively quickly inhabit a covetous place in the popular mindset of its audience. Images of city life are realised in the form of rushing commuters, masks from the nearby British Museum, blaring saxophones mimicking the presence of buskers and abstract patterns exuding a vibrant sense of movement.

While the effectiveness and formal qualities of Paolozzi's work cannot be denied, its ability to do anything more than provide a backdrop to a city limits its scope. People like it because they feel safe with it; it is a recognisable land mark which is beautifully conceived and crafted. But really good art and bold commissioning goes further than this. By presenting artists and audiences with an exploratory space in which they can capitalise on the strangely static feeling that comes with the actions of leaving and arriving, Platform for Art strives to do just this.

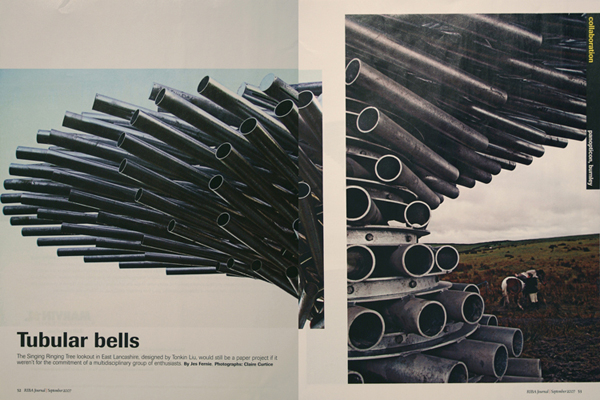

Tubular Bells

RIBA Journal, September 2007

When Jeremy Bentham designed the first panopticon in the late 18th century, he had in mind the rather insidious aim of making prisons more efficient by making prisoners observe and police themselves through fear. He described this precursor to Big Brother as 'a new mode of obtaining power of mind over mind, in a quantity hitherto without example'.

Over a hundred years later, the good people of Lancashire appear to have confounded the more sinister Benthamite qualities of the panopticon by focussing on its physical and aesthetic properties. By commissioning a series of viewing platforms that are situated on elevated sites around towns and cities in the region, the Lancashire panopticons reflect the aspirations and ideals of the surrounding population, rather than police them.

The third of the four panopticons was completed last December in 2006 and was designed by the burgeoning London based architectural practice Tonkin Liu, run by Anna Liu and Mike Tonkin. The Singing Ringing Tree, as it is called, harnesses the sound of the wind through its series of horizontally positioned pipes, producing a haunting whistle in a lonely, wind-swept spot on the moors above Burnley.

Like many architectural practices before them Tonkin Liu has managed to capitalise on the success of a small-scale, financially challenging, experimental project. The publicity and awards that the Singing Ringing Tree received served as a foundation upon which to build a growing practice with increasingly large commissions. But while a lot has been made of the form and properties of the structure, not much has been said of the extraordinary set of relationships that were developed in order to get the project off the ground, realised and in good whistling order.

The first of these relationships was the most serendipitous of them all; the kind of chance encounter that can't be manufactured from a 'phone book. Anna Liu asked another parent on the school run (who she knew to be a sound artist), if he knew of anyone who could help her make pipes sing. The response was: 'Well, only me'. Thus began an intense process of research, discussions and trials between sound artist Dan Knight and Tonkin Liu. This process provided the conceptual framework for the subsequent collaborations that the project demanded, with structural engineer Jane Wernick and fabricator Mike Smith.

Working on an outdoor installation was new to Dan Knight, whose work as a sculptor had hitherto positioned him firmly between four walls. He began his period of research by contacting a professor of engineering in Canada who had recently worked with an artist on a pipe-based sound sculpture. The conditions in which both the Singing Ringing Tree and the Canadian sculpture were made, were similar: the relatively small wind force in the cities of London and Vancouver made it hard to reproduce the wind surges typical of the site's location. Knight and Tonkin Liu adopted the Canadians' rather maverick solution by putting a tube of carefully slit piping in a car which protruded from the windows and driving hell for leather down the road, thus picking up enough speed to create the wind force necessary for assessing the pipes' whistling quality.

Artist and architect initially tried using scaffolding pipes to create the desired sound, but soon found that they were too thin and heavy. In getting so immersed in the attempt to create a decent sound, the team lost sight of the aesthetics of the work. 'Dan acted as a critic at this point, saying 'Don't worry about the sound now - you've got to make it look good''. One of the criteria for the pieces was that it had to be visible from Burnley's temple of consumerism (Sainsbury's), so the aesthetics had to work from far and near.

Initially Tonkin Liu was interested in making a symmetrical shape but Knight persuaded them to work with a more organic tree-like form which made it look like it was leaning into the wind. 'I love the incongruity of it - the fact that it is made of steel and is incredibly strong, but looks like it is being pushed by the wind', says Knight.

Once the concept and general feel of the tree was arrived at, Tonkin Liu worked with structural engineer Jane Wernick who advised on how to make the thing work. Wernick already had an interest in working closely with architects on projects relating to the arts. She worked with Hadid on the Ordrupgaard Museum in Denmark, with Chipperfield on the Figge Museum in the USA, and is currently working with artist Toby Patterson on a project for the BBC in Scotland. This meant that she was able to approach the project as an intellectual challenge rather than one that would offer any kind of financial reward (the fees for all involved were tiny). Wernick enjoys the challenge of working on projects that aren't buildings: 'They often take you right back to first principles - the structure is what you see and conceptual clarity becomes very important. This entails close collaboration and agreement from everyone on the design team'.

After a protracted period of silence on the part of the client, when it was unclear whether the project would go ahead, Wernick and project engineer Kate Purver, devised a system whereby twenty five of the hundred or so pipes that make up the tree would be 'cut to sing' and positioned on steel rings in order to make the most of the location and the seasons on the site. 'When Anna and Mike first came to us, they bought a model made of paper straws stacked on top of each other. It's not possible to weld pipes onto a layer below, so we devised a spiral axis based around two rings with tubes bolted on horizontally' says Wernick. The tree was too heavy and large to be fabricated in London and transported to Burnley, so Wernick and Purver experimented with ways that it could be fabricated and bolted on site in order to spread the load evenly and eliminate knife edges.

As with all projects of this kind, the element of trust and mutual respect among the key players is a crucial part of seeing the project through from concept to realisation. The third and perhaps most significant relationship that Anna Liu and Mike Tonkin established in the making of Singing Ringing Tree was one with Mike Smith, fabricator of choice for any self-respecting artist (he has worked with three of this year's four Turner Prize nominees). Smith was appointed not only to make the tree, but to assume the role of a design and build contractor in the face of a risk averse council whose attachment to cost-certainty was unflinching. 'We had a great working relationship with James Shearer (from Mike's studio) and Mike; they really believed it would work and were totally committed to the project' says Anna Liu, who at one point was resigned to the fact that the tree would remain a myth.

Each of the three collaborations that Tonkin Lui formed during the making of Singing Ringing Tree overlapped with each other. Wernick met with Knight to discuss how the pipes might work and get an idea of the conceptual thrust of the scheme as well as Mike Smith, the fabricator, to liaise with issues regarding on-site fabrication. Smith, in turn, executed beautifully detailed drawings for the contractors in Burnley to refer to when constructing the tree on site.

In addition to these London-based collaborations, Tonkin Liu nurtured a close working relationship with Burnley Borough Council's architect Andrew Rolfe and the local contractor who prepared the foundation on a disused radio station. 'You always need someone on the ground to make a project happen. We had to trust in the Council and the contractors that they would be true to the plans. It was a risk for them too and it paid off' says Anna Liu.

Tonkin Liu's commitment to working in the public realm, encouraging close collaborations between local community groups and councils, meant that this project was ideologically, as well as personally and creatively, driven. It seems clear that without this commitment - to collaboration, experimentation and political ideology - The Singing Ringing Tree would be singing and ringing only on paper.

Over a hundred years later, the good people of Lancashire appear to have confounded the more sinister Benthamite qualities of the panopticon by focussing on its physical and aesthetic properties. By commissioning a series of viewing platforms that are situated on elevated sites around towns and cities in the region, the Lancashire panopticons reflect the aspirations and ideals of the surrounding population, rather than police them.

The third of the four panopticons was completed last December in 2006 and was designed by the burgeoning London based architectural practice Tonkin Liu, run by Anna Liu and Mike Tonkin. The Singing Ringing Tree, as it is called, harnesses the sound of the wind through its series of horizontally positioned pipes, producing a haunting whistle in a lonely, wind-swept spot on the moors above Burnley.

Like many architectural practices before them Tonkin Liu has managed to capitalise on the success of a small-scale, financially challenging, experimental project. The publicity and awards that the Singing Ringing Tree received served as a foundation upon which to build a growing practice with increasingly large commissions. But while a lot has been made of the form and properties of the structure, not much has been said of the extraordinary set of relationships that were developed in order to get the project off the ground, realised and in good whistling order.

The first of these relationships was the most serendipitous of them all; the kind of chance encounter that can't be manufactured from a 'phone book. Anna Liu asked another parent on the school run (who she knew to be a sound artist), if he knew of anyone who could help her make pipes sing. The response was: 'Well, only me'. Thus began an intense process of research, discussions and trials between sound artist Dan Knight and Tonkin Liu. This process provided the conceptual framework for the subsequent collaborations that the project demanded, with structural engineer Jane Wernick and fabricator Mike Smith.

Working on an outdoor installation was new to Dan Knight, whose work as a sculptor had hitherto positioned him firmly between four walls. He began his period of research by contacting a professor of engineering in Canada who had recently worked with an artist on a pipe-based sound sculpture. The conditions in which both the Singing Ringing Tree and the Canadian sculpture were made, were similar: the relatively small wind force in the cities of London and Vancouver made it hard to reproduce the wind surges typical of the site's location. Knight and Tonkin Liu adopted the Canadians' rather maverick solution by putting a tube of carefully slit piping in a car which protruded from the windows and driving hell for leather down the road, thus picking up enough speed to create the wind force necessary for assessing the pipes' whistling quality.

Artist and architect initially tried using scaffolding pipes to create the desired sound, but soon found that they were too thin and heavy. In getting so immersed in the attempt to create a decent sound, the team lost sight of the aesthetics of the work. 'Dan acted as a critic at this point, saying 'Don't worry about the sound now - you've got to make it look good''. One of the criteria for the pieces was that it had to be visible from Burnley's temple of consumerism (Sainsbury's), so the aesthetics had to work from far and near.

Initially Tonkin Liu was interested in making a symmetrical shape but Knight persuaded them to work with a more organic tree-like form which made it look like it was leaning into the wind. 'I love the incongruity of it - the fact that it is made of steel and is incredibly strong, but looks like it is being pushed by the wind', says Knight.

Once the concept and general feel of the tree was arrived at, Tonkin Liu worked with structural engineer Jane Wernick who advised on how to make the thing work. Wernick already had an interest in working closely with architects on projects relating to the arts. She worked with Hadid on the Ordrupgaard Museum in Denmark, with Chipperfield on the Figge Museum in the USA, and is currently working with artist Toby Patterson on a project for the BBC in Scotland. This meant that she was able to approach the project as an intellectual challenge rather than one that would offer any kind of financial reward (the fees for all involved were tiny). Wernick enjoys the challenge of working on projects that aren't buildings: 'They often take you right back to first principles - the structure is what you see and conceptual clarity becomes very important. This entails close collaboration and agreement from everyone on the design team'.

After a protracted period of silence on the part of the client, when it was unclear whether the project would go ahead, Wernick and project engineer Kate Purver, devised a system whereby twenty five of the hundred or so pipes that make up the tree would be 'cut to sing' and positioned on steel rings in order to make the most of the location and the seasons on the site. 'When Anna and Mike first came to us, they bought a model made of paper straws stacked on top of each other. It's not possible to weld pipes onto a layer below, so we devised a spiral axis based around two rings with tubes bolted on horizontally' says Wernick. The tree was too heavy and large to be fabricated in London and transported to Burnley, so Wernick and Purver experimented with ways that it could be fabricated and bolted on site in order to spread the load evenly and eliminate knife edges.

As with all projects of this kind, the element of trust and mutual respect among the key players is a crucial part of seeing the project through from concept to realisation. The third and perhaps most significant relationship that Anna Liu and Mike Tonkin established in the making of Singing Ringing Tree was one with Mike Smith, fabricator of choice for any self-respecting artist (he has worked with three of this year's four Turner Prize nominees). Smith was appointed not only to make the tree, but to assume the role of a design and build contractor in the face of a risk averse council whose attachment to cost-certainty was unflinching. 'We had a great working relationship with James Shearer (from Mike's studio) and Mike; they really believed it would work and were totally committed to the project' says Anna Liu, who at one point was resigned to the fact that the tree would remain a myth.

Each of the three collaborations that Tonkin Lui formed during the making of Singing Ringing Tree overlapped with each other. Wernick met with Knight to discuss how the pipes might work and get an idea of the conceptual thrust of the scheme as well as Mike Smith, the fabricator, to liaise with issues regarding on-site fabrication. Smith, in turn, executed beautifully detailed drawings for the contractors in Burnley to refer to when constructing the tree on site.

In addition to these London-based collaborations, Tonkin Liu nurtured a close working relationship with Burnley Borough Council's architect Andrew Rolfe and the local contractor who prepared the foundation on a disused radio station. 'You always need someone on the ground to make a project happen. We had to trust in the Council and the contractors that they would be true to the plans. It was a risk for them too and it paid off' says Anna Liu.

Tonkin Liu's commitment to working in the public realm, encouraging close collaborations between local community groups and councils, meant that this project was ideologically, as well as personally and creatively, driven. It seems clear that without this commitment - to collaboration, experimentation and political ideology - The Singing Ringing Tree would be singing and ringing only on paper.

Cottrell & Vermeulen

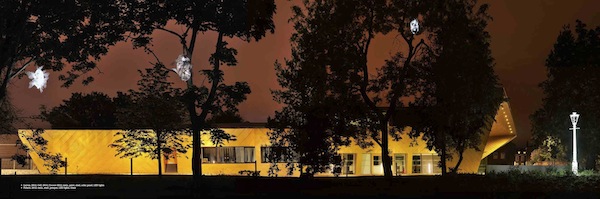

Blueprint, November 2006

'You know the opening scene of The Shining where Jack Nicholson drags himself up a hill towards the isolated hotel where he and his family have chosen to stay for a winter? That's what it was like'. Brian Vermeulen is describing the extreme situation in which he met Richard Cottrell fifteen years ago. The recession in the UK meant that there was little work for aspiring young architects so they packed their bags and took jobs working on the refurbishment of Le Corbusier's Uniti d'Habitation in Marseille. They were living on site working for £75 a week in a fiercely cold apartment, located in a village which boasted a café that shut at 4.30pm. Discovering that they had common interests (primarily, it must be said, a strong interest in getting the first train home) they decided to set up a practice together on their return to England.

They started with a government business grant of £3,000 and now head a growing practice of 12 architects in south London. The fact that there is a lunch rota in the office where people take turns making meals using organic vegetables grown in Vermeulen's allotment tells you quite a bit about the practice. Cottrell & Vermeulen are the funky beard and sandals face of contemporary architecture. They have built a reputation for doing playful things with cheap material for clients who have not a penny to spare. When they first set up practice, they did what most self-respecting young architects do: they called home. Only this wasn't a home in Kent that needed a small but over-laboured extension, but a farmstead in Harare, Zimbabwe. Through working on this project together they established a working practice consisting of research (in this case traditional African symbolism), collaboration with the client and user groups (Brian's parents, farm workers and a small workforce of wood carvers) and recycling (sandstone unearthed from the excavations).

Cottrell & Vermeulen have remained faithful to the client base that they have built up over the last fourteen years. They still work on schools, churches, community buildings and libraries; the difference now is that instead of being asked to build an extension to a school, they're building schools in their entirety. They have just completed a community building for young people in the multi-ethnic London borough of Newham. E13MIX, as it is known, provides 12-21 year olds with a multi-purpose hall, a computer suite, a chill-out room, office space and a courtyard café. This building has no exterior view; it is entered by an innocuous gate on a busy, ramshackle road and occupies a small bit of land sandwiched between a supermarket, a car repair yard, residential gardens and the Newham Race Equality centre. 'In some respects', says Richard Vermeulen, 'it is like Caruso St John's recently completed Brick House in west London in that it is not visible from the outside - the focus is all on the interior. But our building isn't self-referential; it's not an architectural study.' This building perfectly encapsulates Cottrell & Vermeulen's design philosophy: the focus is primarily on the client and out of that comes the architecture. The fact that you can't photograph E13MIX from afar, make it into an icon and objectify it, is pleasing to the architects who are suspicious of the icon driven culture of 21st century architecture. 'We're interested in how to make a building work, what people do in it and how to bring about an inclusive and bespoke solution to often diverse needs' says Cottrell.

The courtyard, with its clay tile flooring and folding laser cut metal screens, is the focal point of E13MIX. Teenagers who attended workshops held by Cottrell & Vermeulen came up with the patterns which are loosely based on Moorish designs. Like the exterior walls of their widely published nursery and community centre in Folkestone (completed in 2004) which are covered in a humorous and elaborate silk-screened giraffe pattern, these interventions provide the building with an identity and a sense of ownership which is a key component in all Cottrell & Vermeulen projects.

If this is all sounding slightly like a knit-your-own-cladding approach to architecture, then that's what it is. However, while many bad architectural practices take their lead exclusively from user groups and pepper their proposals with words like 'engage' and 'inclusive', Cottrell & Vermeulen manage to bypass this trap by creating buildings which work for users and have a stamp of conviction about them. Their innovative use of cheap materials and the way they put them to use spatially is a significant factor in this.

At the recently completed, absurdly named, Bellingham Families & Young People Gateway Building in Lewisham, south London, the asymmetrical wonky roof is made of corrugated translucent glass reinforced plastic, behind which brightly coloured plywood panels are fixed. The surrounding playing field creeps up into the building in the form of sedum which partially covers the east elevation. While the basic finishes are a direct result of the eye-poppingly small budget of £1.2 million, they are also a manifestation of Cottrell & Vermeulen's philosophy. 'We take the idea of value for money very seriously' says Cottrell 'Spending an absurd amount of money on a building is indefensible; opulence for the sake of it isn't our style'.

But opulence is, strangely enough, what often comes to the fore in Cottrell & Vermeulen buildings. However small the budget, there is an abundance of colour, textures and materials which create a sense of luxury or at least bespoke character. As part of the E13MIX workshop programme, the architects took the future users of the building around Philippe Starck's St Martins Lane Hotel in central London, to give them a sense of the possibilities for combining styles and colour. In a sense, Cottrell & Vermeulen are doing what Starck is doing, only with a little less money.

Current work on a Hindu school in north London has provided Cottrell & Vermeulen with an opportunity to apply their in-depth knowledge of school and community architecture to a religious context about which they know very little. Vermeulen says it is, in many ways, a perfect project. Their brief was to find bespoke solutions to a very particular set of cultural, religious, and physical demands such as how to enable bare-foot children to move around a school and how to provide for the all-important rituals relating to food and dance in the Hindu religion. There is pressure on the client to create links with the local community; the school could easily be perceived as an independent institution that caters to a small section of the population. However, this is a state-funded primary school which will offer places to non-Hindu children and this must be reflected in the design. Hence Cottrell & Vermeulen have come up with an unflinchingly contemporary scheme (in collaboration with the future users, of course) which will include bold block-printed patterns on external curtains. The one nod to tradition is the proposal to ship in a ready-made temple from India (a mini-Neasden) which will be linked to the school by a courtyard, at the centre of which will be a contemplative garden.

Brian Vermeulen and Richard Cottrell say that they don't have a strong political agenda and claim that their alignment to a certain type of client was never planned. But while most architects start off with small scale, low budget projects primarily for private clients and move on to (or aspire to move on to) restaurant fit-outs, offices and residential blocks, Cottrell & Vermeulen have steered clear of commercial jobs. 'This is more accident than design but I agree that we aren't natural architects for private clients'. It's not that they don't want to take on large scale projects with half decent budgets (they were short listed, after all, for the phase II development of Tate St Ives two years ago); it's more that their working methodology militates against them. Their commitment to the idea that architecture is a social art is something that many architects may agree with but find hard to carry through when lured by a half decent fee.

It would be interesting to see what Cottrell & Vermeulen would do with a realistic budget. Would the absence of severe restraints prove too much for them? Where would the challenge lie? Most pressingly of all, would they start buying BLT sandwiches from Pret a Manger?

They started with a government business grant of £3,000 and now head a growing practice of 12 architects in south London. The fact that there is a lunch rota in the office where people take turns making meals using organic vegetables grown in Vermeulen's allotment tells you quite a bit about the practice. Cottrell & Vermeulen are the funky beard and sandals face of contemporary architecture. They have built a reputation for doing playful things with cheap material for clients who have not a penny to spare. When they first set up practice, they did what most self-respecting young architects do: they called home. Only this wasn't a home in Kent that needed a small but over-laboured extension, but a farmstead in Harare, Zimbabwe. Through working on this project together they established a working practice consisting of research (in this case traditional African symbolism), collaboration with the client and user groups (Brian's parents, farm workers and a small workforce of wood carvers) and recycling (sandstone unearthed from the excavations).

Cottrell & Vermeulen have remained faithful to the client base that they have built up over the last fourteen years. They still work on schools, churches, community buildings and libraries; the difference now is that instead of being asked to build an extension to a school, they're building schools in their entirety. They have just completed a community building for young people in the multi-ethnic London borough of Newham. E13MIX, as it is known, provides 12-21 year olds with a multi-purpose hall, a computer suite, a chill-out room, office space and a courtyard café. This building has no exterior view; it is entered by an innocuous gate on a busy, ramshackle road and occupies a small bit of land sandwiched between a supermarket, a car repair yard, residential gardens and the Newham Race Equality centre. 'In some respects', says Richard Vermeulen, 'it is like Caruso St John's recently completed Brick House in west London in that it is not visible from the outside - the focus is all on the interior. But our building isn't self-referential; it's not an architectural study.' This building perfectly encapsulates Cottrell & Vermeulen's design philosophy: the focus is primarily on the client and out of that comes the architecture. The fact that you can't photograph E13MIX from afar, make it into an icon and objectify it, is pleasing to the architects who are suspicious of the icon driven culture of 21st century architecture. 'We're interested in how to make a building work, what people do in it and how to bring about an inclusive and bespoke solution to often diverse needs' says Cottrell.

The courtyard, with its clay tile flooring and folding laser cut metal screens, is the focal point of E13MIX. Teenagers who attended workshops held by Cottrell & Vermeulen came up with the patterns which are loosely based on Moorish designs. Like the exterior walls of their widely published nursery and community centre in Folkestone (completed in 2004) which are covered in a humorous and elaborate silk-screened giraffe pattern, these interventions provide the building with an identity and a sense of ownership which is a key component in all Cottrell & Vermeulen projects.

If this is all sounding slightly like a knit-your-own-cladding approach to architecture, then that's what it is. However, while many bad architectural practices take their lead exclusively from user groups and pepper their proposals with words like 'engage' and 'inclusive', Cottrell & Vermeulen manage to bypass this trap by creating buildings which work for users and have a stamp of conviction about them. Their innovative use of cheap materials and the way they put them to use spatially is a significant factor in this.

At the recently completed, absurdly named, Bellingham Families & Young People Gateway Building in Lewisham, south London, the asymmetrical wonky roof is made of corrugated translucent glass reinforced plastic, behind which brightly coloured plywood panels are fixed. The surrounding playing field creeps up into the building in the form of sedum which partially covers the east elevation. While the basic finishes are a direct result of the eye-poppingly small budget of £1.2 million, they are also a manifestation of Cottrell & Vermeulen's philosophy. 'We take the idea of value for money very seriously' says Cottrell 'Spending an absurd amount of money on a building is indefensible; opulence for the sake of it isn't our style'.

But opulence is, strangely enough, what often comes to the fore in Cottrell & Vermeulen buildings. However small the budget, there is an abundance of colour, textures and materials which create a sense of luxury or at least bespoke character. As part of the E13MIX workshop programme, the architects took the future users of the building around Philippe Starck's St Martins Lane Hotel in central London, to give them a sense of the possibilities for combining styles and colour. In a sense, Cottrell & Vermeulen are doing what Starck is doing, only with a little less money.

Current work on a Hindu school in north London has provided Cottrell & Vermeulen with an opportunity to apply their in-depth knowledge of school and community architecture to a religious context about which they know very little. Vermeulen says it is, in many ways, a perfect project. Their brief was to find bespoke solutions to a very particular set of cultural, religious, and physical demands such as how to enable bare-foot children to move around a school and how to provide for the all-important rituals relating to food and dance in the Hindu religion. There is pressure on the client to create links with the local community; the school could easily be perceived as an independent institution that caters to a small section of the population. However, this is a state-funded primary school which will offer places to non-Hindu children and this must be reflected in the design. Hence Cottrell & Vermeulen have come up with an unflinchingly contemporary scheme (in collaboration with the future users, of course) which will include bold block-printed patterns on external curtains. The one nod to tradition is the proposal to ship in a ready-made temple from India (a mini-Neasden) which will be linked to the school by a courtyard, at the centre of which will be a contemplative garden.

Brian Vermeulen and Richard Cottrell say that they don't have a strong political agenda and claim that their alignment to a certain type of client was never planned. But while most architects start off with small scale, low budget projects primarily for private clients and move on to (or aspire to move on to) restaurant fit-outs, offices and residential blocks, Cottrell & Vermeulen have steered clear of commercial jobs. 'This is more accident than design but I agree that we aren't natural architects for private clients'. It's not that they don't want to take on large scale projects with half decent budgets (they were short listed, after all, for the phase II development of Tate St Ives two years ago); it's more that their working methodology militates against them. Their commitment to the idea that architecture is a social art is something that many architects may agree with but find hard to carry through when lured by a half decent fee.

It would be interesting to see what Cottrell & Vermeulen would do with a realistic budget. Would the absence of severe restraints prove too much for them? Where would the challenge lie? Most pressingly of all, would they start buying BLT sandwiches from Pret a Manger?

Space Soon

Blueprint, October 2006

It's 1969. Man has just taken his first step on the moon and Pete Townsend is on stage at the Roundhouse in London, smashing his guitar during the finale of My Generation. These acts mark the end of a decade now viewed with a mixture of nostalgia and awe. Thirty seven years later we are more sceptical: the Space Race is on hold, pop stars synchronise their outbursts with the pulse of the media, and artists are building rockets made of discarded toothpaste tanks and tyres which are quite clearly going nowhere.

A London-based organisation, The Arts Catalyst, has been developing projects over the last thirteen years which critique our society's limited view of science, and this September will see a major culmination of that work. International artists have been commissioned to make work which reflects on the apparently insatiable human desire to explore and appropriate space. Sited in and around the newly refurbished Grade II listed performance arts venue, the Roundhouse, these works are the antithesis of all that the Space Race stood for in the 1950s and 60s. Where the approach to space travel was once optimistic, bombastic and male dominated, here it takes on a reflexive, poignant and altogether more critical approach which proffers more questions than it does answers.

Buckminster Fuller's response to Neil Armstrong's momentous Moon landing was "We are already in space". This idea has been taken up by the Danish art collective N55 and Neal White (a UK-based artist) whose collaborative project Space on Earth Station consists of pod-like dwellings, supported on tripods, located in the immediate vicinity around the Roundhouse. Reminiscent of the first Lunar Module, these geometric forms, whose shape is derived from a truncated octahedron, house research stations dedicated to the study of local conditions in the area. Crew members consist of humans, bees, fish and plants, all of whom will be used as organic filters, collecting data concerning contamination and living conditions in the hostile environment of NW1. In this project N55 (named after a street address and degree of latitude in Copenhagen) presents a critique of the top down model of space institutions in favour of a more experimental and democratic process. A significant part of the project is to encourage participation from anyone interested in carrying out research into alternative ways of life, including research into renewable foodstuffs, the psychological effects of confined living, and even possible sexual constellations.

N55 was founded by Ion Sorvin and Ingvil Aarbakke, a husband and wife team, who were evangelical about the fact that material goods ought to be shared and saved from the constraints of private ownership. Aabakke died of cancer in 2005 (at the age of 35) but she played a key part in the development of Space on Earth Station and the work of N55 is continued by Sorvin. In 1999 the group became known for the curious-looking object they constructed at Copenhagen's harbour where they lived and worked. Spaceframe is a tessellated tetrahedric construction (that's a 'four-sided mosaic thing' to you and me) with a floor space of 20 square meters, no foundations and a self-assembly frame. N55's work is a cross between the ideas expounded by the 19th century French philosopher Proudhon (property is theft and anarchy is order), and those futuristic fibreglass architectural pods made by Atelier van Lieshout which seep biomorphic growths and ooze 70's chic. Although Spaceframe is made using cutting edge technology it is a spur to the revival of a nomadic way of life and a reminder that we are tenants rather than freeholders on planet earth.

The Polish artist Aleksandra Mir (a space station in her own right) has taken an equally oblique look at space travel culture by converting the Roundhouse into a fake rocket factory. Mir rose to art world fame in 1999 when she became the first woman to walk on the moon, or at least to stage an elaborate moon landing on a sand dune on a beach in Holland. Mir says she "wanted to beat JFK to his word of putting a man on the moon and bringing him back safely to earth before the end of the decade. I wanted to put a woman on the moon before the end of the millennium, knowing very well that this wasn't going to happen". Her aim was to contribute to the grand narratives of mass aviation and popular culture which she acknowledges have a significant influence on how we perceive ourselves in the world. "To contribute to these narratives as an artist means that I can attempt to formally mimic their orchestration but, in a scale of David vs. Goliath, also reveal my vulnerability and incompetence, speaking for all those narratives in the backwater of utopia that remain untold."

Mir continues to explore this incompetence theme in Gravity, her installation at the Roundhouse. She has converted the stunning interior space of the building into a rocket factory much like NASA's 'barn' at the Kennedy Space Centre, thereby taking the Roundhouse closer to its original industrial use as a steam engine repair shed. A 20 foot rocket sits at the centre of the building on the circular stage reaching up to the cast and wrought iron structure that makes up the roof. The rocket is entirely constructed out of junk. The bottom part of it measures 3 meters in diameter and is a disused tank from a tooth paste factory in Sheffield. Other discarded items such as heavy-duty vehicle tyres, pipes and containers make up the body of the rocket. The idea of using found objects, cultural residue and garbage, she says, "stands in direct opposition to the idea of utopia promised by new shiny things. It also means that I can work with a ready-made aesthetic, using stuff that is already full of stories".

Snapshots taken at the site of Mir's junk discoveries show her in semi-ironic poses smiling at the camera in a way that is at odds with her insalubrious surroundings. She is collecting these photographs to create a "pin-up calendar of sorts" and refers to the industrial sites in which they are taken as 'Man World'. The photographs become part of the work (the only lasting physical evidence of the project) and tell the story of a woman who has landed in a strange and exotic place, a place that might as well be another planet.

If Mir was the first woman on the moon, the artists Jane and Louise Wilson were one of the first to get behind the scenes at the notoriously secretive Russian Space Agency. In 2001 they made a film called Dreamtime which consists of footage of the formal preparations for the launch of the International Space Rocket, in Baikonur Cosmodrome, Kazakhstan. The Cosmodrome is at the centre of the Russian space programme; it was from here that Yuri Gagarin became the first man to be launched into space in 1961. In the film, steam from the launch-site drifts into view, heavy coated soldiers stamp about in the cold and deserted conference rooms and empty corridors evoke an eerie silence. The stage is set for the rocket launch which creates a spectacular display of orange flames and smoke (although I am told that this was a mistake - the Wilson twins managed to bribe a Russian guard to get nearer the rocket, but they got too near and missed out on the blast off view). Dreamtime is part of The Arts Catalyst's extensive programme of films, talks and live events taking place at the Roundhouse alongside the installations by N55, Mir and others. One of the talks is by Alan Bean, one of the twelve men who walked on the moon and the only one to become a professional artist on his return from space.

Nicola Triscott, director of The Arts Catalyst, on being asked what artists can bring to a discussion on science, has said "Artists can show that there is a much wider human motivation in these great enterprises…, scientists need to be reminded that there is a multitude of ways at looking at things". Space Soon (a cryptic way of saying that all points of departure are illusory as zero comes both before and after nine in the decimal system) is a radical and bold exploration of what it is to be human.

President Bush recently announced a new multi-billion dollar NASA programme to explore the solar system but the next generation of British astronauts will have to forego their citizenship if they want to clamber around on Mars. Back in the 70's Thatcher stopped UK contributions to the European Space Agency in a cost-cutting exercise and they've never been reinstated. Maybe the next generation would be better employed sifting through junk yards hunting for the perfect toothpaste tank.

A London-based organisation, The Arts Catalyst, has been developing projects over the last thirteen years which critique our society's limited view of science, and this September will see a major culmination of that work. International artists have been commissioned to make work which reflects on the apparently insatiable human desire to explore and appropriate space. Sited in and around the newly refurbished Grade II listed performance arts venue, the Roundhouse, these works are the antithesis of all that the Space Race stood for in the 1950s and 60s. Where the approach to space travel was once optimistic, bombastic and male dominated, here it takes on a reflexive, poignant and altogether more critical approach which proffers more questions than it does answers.